For decades, you could rely on the world of design media to resemble a game of musical chairs. Every few years there was a shuffle, a few editors and publishers would swap mastheads, and then everyone got back to business as usual. Recently, something different has been happening: When the music stops, the players are leaving the room. Often, they go to work for a brand.

A few high-profile examples from last year alone: Beth Brenner, the founding publisher of Domino, left Galerie to join cabinetry brand Semihandmade; Kelsey Keith, the editor in chief behind Curbed’s critical success, joined Herman Miller as editorial director; Keith Pollock, digital director of Architectural Digest, decamped to join West Elm as senior vice president of creative. Movement at the top has been echoed at lower levels of the masthead, with staffers at publications ranging from Domino to Traditional Home departing for design industry brands.

To be fair, hand-wringing over the future of publishing is nothing new (and often overblown). However, a variety of factors, from the destabilization caused by COVID to an increasingly complex digital landscape, are shifting the center of gravity in design media. I asked Brenner if, now that she’s working for a brand, any former publishing colleagues have approached her with rescue pleas. “Yes!” she says, with a laugh. “People are at a crossroads. It’s a good time to reinvent yourself.”

Michael Boodro, the former editor in chief of Elle Decor and now a podcast host for Chairish and a consultant for the Design Leadership Network, put it in starker terms. He told me he never considered going to another publication after leaving Elle Decor in 2017, and hasn’t looked back at traditional publishing since. (His successor, Whitney Robinson, is also pursuing work oustide publishing after departing Elle Decor in 2020.) “I will say this,” says Boodro. “If someone loses a job at a magazine at this point … it used to be that there were five other magazines to go to. Now there’s not.”

DOING MORE WITH LESS

“Design media” is not a unified entity. The struggles at Architectural Digest are very different from those at Apartment Therapy. But whether they run a blog or an international brand, design publishers are dealing with the same two challenges as all publishers in the digital age: Print advertising isn’t as lucrative as it used to be, and making money online is complicated. Design media has the additional wrinkle of being uniquely vulnerable because of its small advertiser base. “The legacy titles [have been] hanging on by a thread because of the stagnant advertising market and the abundance of content online,” explains Brenner. “And the online channels [aren’t] growing because those same advertisers [are] slow to support them.”

It’s an era of consolidation. In 2013, Hearst combined the editorial teams at Elle Decor, House Beautiful and Veranda (though those teams have since been separated, the company has grouped the marketing and sales teams of the three magazines with Town & Country for greater efficiency). In 2016, Condé Nast debuted “hubs” for its creative, copy and research teams, which means AD shares those services with other titles. In 2019, Meredith revamped Traditional Home and reduced its editorial staff. In the past decade, several major design magazines have trimmed their mastheads and cut down on their frequency to publish four or six issues a year instead of 10 or 12.

Increasingly, editors are pressured to do more with less. In an interview with BOH in 2018, former House Beautiful editor in chief Sophie Donelson described dwindling production budgets that weren’t necessarily matched by dwindling expectations. “What used to be a three-day shoot became a two-day shoot, what used to be a two-day shoot became a one-day shoot,” she recalled. “You don’t have the resources to take risks.” Boodro had a similar experience. “Quite frankly, the last couple of years at Elle Decor, it was managing decline,” he says. “It wasn’t fun anymore.”

Into an already uncertain landscape, COVID has introduced yet more uncertainty. Media companies across the board have been hobbled as clients slashed their advertising budgets. The New York Times estimates that (roughly) 37,000 media workers were laid off, furloughed or saw their pay cut since the arrival of the pandemic.

It’s not clear whether design media has been hit as hard by COVID. Certainly in March of last year, as the economy slowed to a crawl, there was widespread internal panic in the shelter magazine world as advertisers either jumped ship or put their plans on pause. But as Americans are spending more on their homes, advertisers are slowly returning. Several publishing executives told me that their clients are looking to spend big in 2021, but it’s yet to be determined whether the spoils of a flourishing home economy will prop up a traditional print advertising model.

THE PROMISE OF DIGITAL

Long-term, the bright spot for design media likely isn’t a post-COVID bump in demand for print, but the potential of cracking the code online, where publishers can chase the rising digitally native generation without the exorbitant costs of producing and distributing a physical magazine. Though the pandemic’s effect on the digital ad market is murky, it has unquestionably boosted online traffic—most home world publishers will tell you that their site analytics have been setting records over the past 12 months. Clearly, there’s opportunity online.

The problem with digital media is that the rules change every few years. Seemingly arbitrary decisions by Facebook or Google can eliminate entire business models overnight, and traditional advertisers have never paid the same rates for a banner ad as they might have for, say, a spread in AD. Currently, the monetization strategy du jour in digital media is to try and get readers to pay for content. But while that approach has worked for prestige journalism outlets like The New York Times and The New Yorker, it’s less clear that an online subscription model can succeed in the world of shelter publishing, where consumers have become acclimated to seeing endless design inspiration for free on Instagram and Pinterest. (House Beautiful has placed some of its online content behind a paywall, and Condé Nast announced in early 2019 that it would put all of its U.S. brands’ digital content behind a paywall by the year’s end, though the rollout does not appear to be complete.)

Instead, most digital design publishers tend to take a kitchen-sink approach, blending a mix of display advertising, programmatic ads, affiliate marketing, native advertising, events, and social promotion tie-ins into what (hopefully) amounts to a profitable business. Hunker, the Los Angeles–based digitally native shelter publication founded in 2017 is a case study. It does all of the above, plus the occasional dalliance into manufacturing product, and it has its own content creation studio.

Eve Epstein, Hunker’s vice president of content and a rare media optimist, says that there are plenty of reasons to be hopeful about growth in digital—you just have to be scrappy and inventive. “The watchword for publishers is that you can’t just be good at one thing. You have to always look at what you’re really adding to the conversation,” she says. “We have to do better at everything now.”

In other words, digital design media is a lively, engaging business, but not a particularly stable one. Nor is it a great place to get rich. “For most people who work in editorial, there’s a ceiling and it feels fairly low, particularly if you’re not in a Condé Nast–type structure,” says Epstein. “There’s no equivalent of Anna Wintour at a digital publication. For people who are particularly ambitious, there are more things outside of publishing than there ever were before.”

Of course, individual people go to brands for individual reasons. Keith, who worked at Dwell and Architizer before leading Curbed to critical success, says that she had been considering other jobs in publishing, and that her decision to go to Herman Miller in November was mostly about wanting to work for Herman Miller, not a grand, final departure from media.

Similarly, Pollock wrote in an email that he had long wanted to go over to the brand side—and specifically West Elm. (“A former colleague of mine from Elle contacted me after the announcement and said, ‘Do you remember you told me you wanted to be creative director of West Elm someday?’” he recalls.) However, both Pollock and Keith agreed that the murkiness of the media business model was a challenge.

“As digital media has expanded and provided so much to readers for free, the sense of what people are getting has gotten muddled and internal metrics for success are always shifting,” says Keith. “Whether you think of Herman Miller as a design company, a performance chair company or the manufacturer of Eames furniture, the measures of success are much more clear, and that part of it is very appealing.”

Pollock, who has spent most of his career in media (he worked for Elle, DuJour and Interview before AD) put it simply: “Publishing [as an industry] in general is still identifying how to get readers to pay for content.”

A BRANDED GOLDEN AGE

While readers may not want to pay for content, brands are increasingly willing to foot the bill. It’s worth taking a moment to marvel at how rapidly an entire branded content ecosystem has sprung up and matured. A few decades ago, only airlines and credit card companies had their own publications. Now, it seems like everyone has a magazine, blog, podcast—or at least an Instagram Live series.

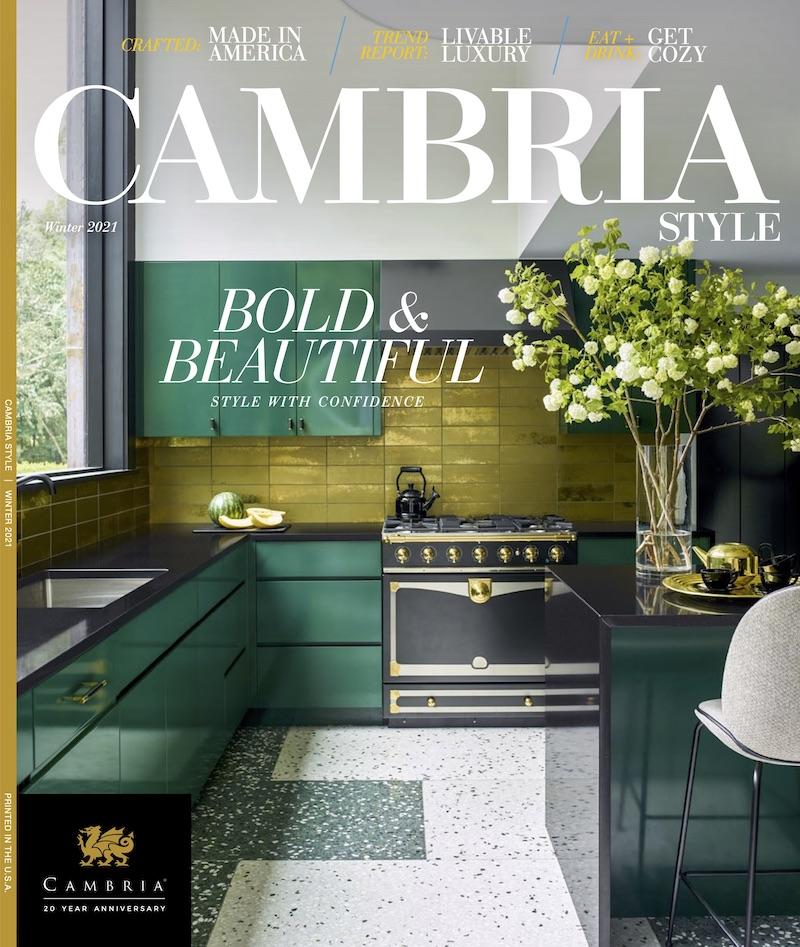

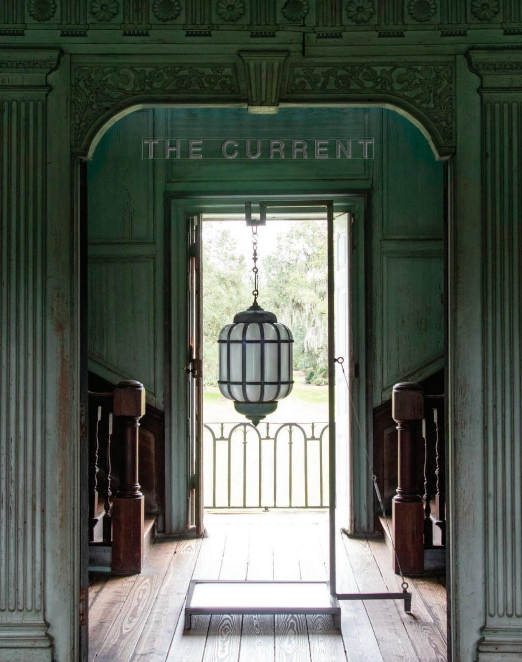

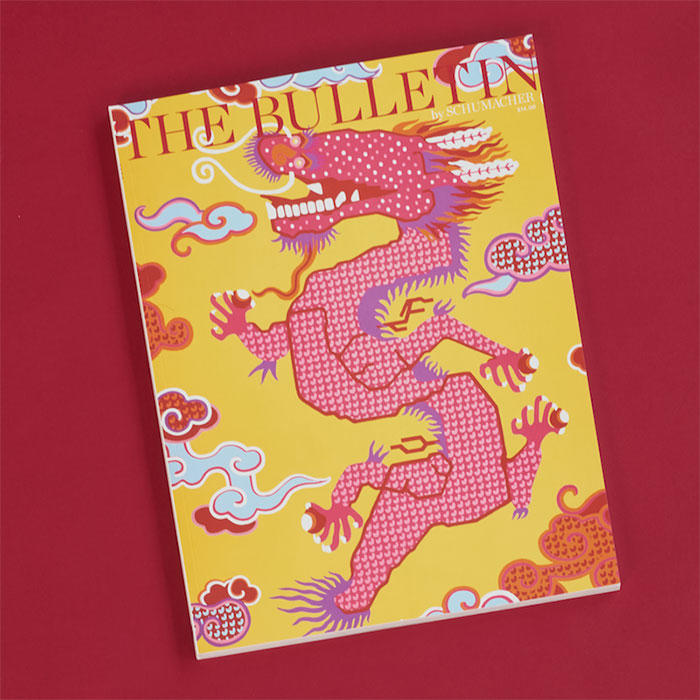

A brief list of branded content ventures, taken only from the world of home: California Closets has a print magazine, Ideas of Order; Schumacher has The Bulletin; Urban Electric has a print magazine, The Current; Semihandmade has a blog, SemiStories; 1stdibs has a blog and print magazine, Introspective; Seasonal Living has an eponymous digital magazine; Great Jones has a blog, Digest; Floyd has a blog, Lived In; Cambria has Cambria Style; the list goes on and on. (Add podcasts to the mix, where brands like Chairish, Modsy, Universal Furniture and Ballard are making their mark, and the list grows even longer.)

Editorial content has gone from “nice to have” to “must have” for a brand putting together a marketing strategy. In a small but telling example, British entrepreneur Carmine Bruno is launching an online antiques marketplace this spring (The Bruno Effect), but though his site isn’t yet open for business, he has already spun up an online magazine (The Effect) featuring articles on wellness and interior design post-COVID.

What’s behind the boom in branded content? A few things. For companies that launched their own print magazines a decade ago, the move was largely a sales tool—a way to concisely convey the brand through the appeal of a glossy print magazine. Cambria Style, launched in 2008 by Minnesota-based quartz surfaces giant Cambria, fits the bill.

“It’s a leave-behind, a calling card, it’s an introduction, it’s a tool of every sort [for sales reps],” says LouAnn Haaf, Cambria Style’s longtime editor in chief and the company’s senior vice president of brand and content. “It got them into doors they may not have gotten into.”

As the magazine built up a following (it helped that Cambria founder Marty Davis also owned Sun Country airlines at the time—seatback pocket placement helped the magazine reach a circulation of 1 million at its peak), the tone began to shift toward a stealthier approach. Cambria product names weren’t as prominently displayed. Bigger celebrities graced the cover (Haaf says the publication is increasingly turning down stars for the cover these days, recently passing on Hilary Swank). Cambria Style began to look less like a Cambria sales tool and more like a traditional lifestyle magazine.

“We’ve become more confident as the magazine evolved,” says Haaf. “A lot the pitches we get are from people who don’t even have Cambria, not realizing that we’re a custom-branded publication … which I think is a testament to the fact that we’re able to straddle that difficult line of pushing our brand forward without tooting our horn so loudly that people aren’t interested in what we have to say.”

Cambria certainly wasn’t alone. As consumers have become increasingly distrustful of blunt sales pitches and obsessed with “authenticity,” brands have sought to make their pitch with a softer, more story-driven approach. Often, that meant hiring editors. In 2015, Schumacher launched The Bulletin, helmed by creative director Dara Caponigro, a former shelter magazine editor. One Kings Lane was another early entrant into the content-driven commerce game, and the online reseller went after design editors from prominent publications in its early years.

Each brand approached the concept in a different way, but the idea was the same: Draw customers into your world with a compelling editorial product, and they’re more likely to buy something expensive. The rise of digital adoption has simply created more opportunities for that dynamic to play out—and as the cost of acquiring customers through Google and Facebook continually rises, brands large and small are looking to hook audiences with a content-driven approach. The internet has also lowered the barrier to entry. With the aid of off-the-shelf software, brands can generate an in-house digital publication, newsletter or podcast cheaply and quickly.

It’s possible, too, that there’s an element of hype driving the explosion of brands starting their own publications, suggests Brenner. “It’s like opening a bar because it’s the cool thing to do,” she says. Epstein agrees. “Nobody values affiliate marketing more than publishers, and nobody values content more than brands,” says the Hunker VP. “It’s a little bit of a ‘grass is greener’ thing: We love our old way of doing things, but this new way is going to be it.”

AGAINST THE CURRENT

Whatever the cause, as branded content has boomed, it has sometimes come at the expense of traditional publishing. To pay for the editorial staff required to make content, brands inevitably dip into the budgets they would normally set aside for advertising. Sometimes it’s a stark either/or choice.

In a conversation that surely would send chills up the spines of traditional publishers, The Urban Electric’s director of marketing, Missy Hulsey, explained to me that a few years back, the South Carolina–based lighting brand had pulled out abruptly from all its advertising in favor of publishing its own magazine, The Current.

“[Urban Electric founder and CEO] Dave [Dawson] was saying, ‘Ads are getting so expensive, and we can’t even see what’s happening with them. We’re putting this money out there and thinking it’s working, but we really have no idea. What if we stopped advertising?’” she recalls. “The whole team was like, ‘No, absolutely not.’ It seemed really drastic.” Nonetheless, the company took the plunge and began putting together The Current, a highly produced print product on thick paper stock that more closely resembles an artsy lifestyle magazine than a catalog.

Not only did Urban see no dropoff in sales, says Hulsey, it found that pulling out of advertising didn’t hurt its ability to place product in editorial coverage. (Prepare to be shocked: Magazine editors typically tend to favor advertisers when putting together stories.) “It gave us the confidence to say that we can take this budget and allocate it into something beautiful that we can control 100 percent of the time and know exactly whose hands it’s going into,” she explains.

To be sure, for brands interested in quickly reaching a large audience—especially new brands—it’s still a lot easier to take out an ad than it is to invent your own publication. The difference is that historically, most marketers would have never thought to try. Now, the option is on the table.

ROOM TO GROW

While it may cause trouble for media conglomerates, a boom in branded content has created opportunities for individual editors and publishing executives (and photographers and graphic designers) eager to take a break from an industry in upheaval. For many, a key motivation for the switch is less about a big salary hike (at least anecdotally, it wasn’t clear to me that brands pay their editorial staff exponentially more than media companies do) and more about stability and clarity of purpose.

“If you’re at a Condé Nast [publication] and it all ends—not because of anything you did, but because of conditions in the market—there’s a lot of head-scratching going on [about what to do next],” says Brenner. “I don’t know if there’s more money on the brand side, but there’s more opportunity to control your fate. I was looking for something that had the potential to grow.”

Anna Logan, the market editor for One Kings Lane’s editorial department, came to the site from Traditional Home after the Meredith title was revamped. “There were a few [traditional media] jobs out there, but there were more opportunities in the branded world to grow,” she says. “You can take it from the brand side and have the same sensibilities and standards [as traditional media], but with the security of a brand behind you.”

Indeed, making the jump from publishing company to branded media is particularly smooth in the design world simply because there’s increasingly little difference between the two. As branded content has gotten more sophisticated, it’s come to more closely resemble traditional shelter media. On the other side of the coin, the rise of affiliate marketing (and ever-cozier relationships with advertisers) has made design media more closely resemble branded content, especially online.

If you skip back and forth between, say, Floyd’s blog and AD’s millennial-oriented vertical Clever, the style and tone of content isn’t radically different. (Try to guess which article came from which outlet: “How to Fend Off the Winter Blues,” “Push/Pull: The History of Sea Ranch,” “This Notting Hill Townhouse Features a 3-in-1 Living Space,” or “Amber Lestrange’s Laurel Canyon Retreat.”) Yes, Floyd is selling Floyd, but Clever is earning affiliate commissions through linked products. More and more, everyone is doing a version of the same thing.

As a result, editors can reasonably expect to hop over to the brand side without their job description changing much. Whether brands are really more stable—that depends on the brand, but the business model offers a reassuring clarity. Brands sell stuff. Publications … well, they’re figuring it out. Where would you rather work?

Homepage photo: © Olllinka2/Adobe Stock