Earlier this year, F. Schumacher & Co. quietly acquired the digital assets of erstwhile online design platform Homepolish, which went under in September 2019. This morning, the company launched a new website (and rebranded Homepolish’s social media accounts as @JoinFreddie) to announce the debut of Freddie, a to-be-developed membership community for interior designers that aims to amplify the to-the-trade industry by encouraging consumers to engage with decorators. (The name is a playful nod to Frederic Schumacher, who founded the New York–based design house in 1889.)

The new brand’s development has been spearheaded by Schumacher president and CEO Timur Yumusaklar and creative director Dara Caponigro, along with Stephen Puschel, the fifth-generation owner of F. Schumacher & Co., which includes Schumacher and rug and carpet brand Patterson Flynn Martin. The three also brought on Homepolish founder Noa Santos as an adviser to help shape Freddie around Homepolish’s original purpose while offering guidance on how to sidestep some of the challenges his company faced.

“I still very much believe in what we were doing with Homepolish—the mission of helping designers build their business by helping them find clients,” Santos tells Business of Home. “I also want to make sure that Freddie is set up for as much success as possible, and that it is not falling into the same potholes that [Homepolish] might have fallen in over the years—[because] I’m intimately familiar with those potholes.”

Founded in 2012 by Santos and early Buzzfeed employee Will Nathan, Homepolish offered designers a steady stream of leads, marketing muscle, and back-office support. In exchange, the company kept a percentage of the designers’ hourly rates. At the time, its approach—especially its embrace of clear pricing and entry-level budgets—was revelatory in an industry that largely chases only the biggest projects. For several years, it worked well: Designers built healthy businesses with Homepolish’s leads, and clients were happy. But by 2016, facing mounting competition from well-funded online competitors that had entered the scene, the company announced a $20 million round of funding. The resulting pressure to turn a profit, fast, led the company to implement unpopular features—an unwieldy project management tool designers had little incentive to use, a hastily built platform matching clients with contractors, and a more restrictive contract structure. Running low on cash, Santos looked to raise another round of funding to keep the company afloat, but a deal never materialized and Homepolish shuttered dramatically last fall, leaving many designers owed thousands of dollars for their work.

In the aftermath of Homepolish’s collapse, Santos went looking for the right buyer for the company’s most valuable assets—an Instagram account with 1.8 million followers, a robust presence on Pinterest, and email newsletter lists reaching both designers and consumers. (A Marker story in February suggested that one early model he considered was a subscription service where designers and clients pay to be matched.) Once the partnership with Schumacher was secured, Freddie was developed throughout the spring and summer, in part in reaction to the dramatic ways COVID has reshaped consumer thinking.

“What’s wonderful about having Schumacher as a partner is that it is in stark contrast to the venture-funded history we had,” says Santos. “Obviously we want to make money, but there aren’t the same expectations that come with venture capital funding. The sense that this is something that’s meant to be built slowly and with care—in the spirit of the original Homepolish, when we were self-funded—is why I was particularly excited to find this partnership.”

While the vision for Freddie is in place, the specifics of its development will evolve over time. In its first phase, the brand’s landing page invites designers to request an invitation for membership. In return, Freddie’s initial offering includes exposure on its social media platforms and in email newsletters. Future additions to the platform will likely include a matchmaking tool to more directly connect designers with potential clients, as well as community-building features that enable designers to pick up business best practices from one another. “What we’re trying to do is start low and iterate, listening to the participants on the platform,” says Santos. “In the beginning, we’re using the assets to help designers generate business. The obvious best way for us to do that is with our marketing channels.”

The work of Freddie’s three founding members—designers Paloma Contreras, Celerie Kemble and Mark D. Sikes—is currently showcased on a page dedicated to featured members, but Yumusaklar says he expects members to ultimately range from emerging to established designers. “Once we launch, we’ll have a really exciting group [of founding members] to help us make the whole community a real success,” he says. “Helping decorators build out their businesses will help them to strengthen the industry at large. Not everybody has the time or resources to build [a social media following] out themselves, so I feel we can be very helpful as a great starting point.”

It’s a concept that has precedent. Homepolish in its heyday provided a launchpad for designers who are now inching toward stardom, from Ariel Okin to Orlando Soria. And though Freddie is launching without much of the back-end operations that powered Homepolish, its marketing capabilities remain powerful tools. “One of the things we did particularly well with Homepolish was to understand how these platforms all interact with each other—how, through the customer journey, someone is first exposed, and then they see it again and again,” explains Santos. “On average, it takes being exposed to something five times before you convert. So the idea is: How do you create that multi-touch experience that gets the person who is thinking about doing their kitchen in six months to actually reach out?”

Throughout its many incarnations, one of Homepolish’s greatest strengths was clarity for consumers: The company established an uncomplicated path to finding, hiring and working with a designer. It also acted as a custodian through a stressful process, offering the security of knowing that there was a larger company involved to manage billing and referee misunderstandings. Without that standardization or perceived guarantee, however, the path to consumer confidence will likely be more complicated.

“The most important thing is to keep it focused and simple,” adds Yumusaklar. “We’re not in the business of losing money, but this is coming from a place of strengthening our industry rather than [us] figuring out how we can make the most money off it. The main idea is that we’re building a great community and a great stage. That’s our mission, and that’s what connects us to the mission of Homepolish when it started out, which was to empower designers and provide the necessary resources.”

While Freddie’s membership fee is expected to generate some revenue, its founders say there’s no external pressure to fast-track profit-driving initiatives on the platform. In fact, Yumusaklar is just as adamant about what Freddie will not become as he is about its potential. For example, unlike Homepolish, Freddie will remove itself from the design process once it links a designer with a client, and the platform will not take a cut of the designer’s fee. He is also adamant that the site will not evolve into a project management tool or a marketplace, and that it won’t be another marketing vehicle for the Schumacher brand. “It’s very much open for other brands—we’ll definitely post images of everybody’s product,” says Yumusaklar. Santos agreed that, in general, the account’s Instagram followers may not even notice a shift beyond the name change: “The channel will stay by and large almost identically what it was, which was promoting designers’ work.”

Freddie’s basic business mission to help designers is not a new one. Its current model recalls Dering Hall’s original business plan, which, when it was founded in 2011, promised designers exposure, help getting projects published and a listing in an online directory in exchange for a membership fee. The matchmaking component has also gained digital legs of late: Several membership-based platforms have debuted in the past year, from Estee Stanley’s agency, The Eye, to Interior Collab, a nonprofit founded by former Homepolish designers after the platform went offline, which has grown into a collective of nearly 30 firms.

But Freddie is certainly a product of the current climate, motivated in part by an underlying concern that consumers are increasingly turning to online resources and major retailers—from Wayfair to West Elm to RH—for design inspiration and expertise. As it presents viable alternatives to well-known retail options on a consumer-facing platform, Yumusaklar sees Freddie as a big-picture play that helps trade brands by supporting their customers (designers) in attracting their customers (consumers) in hopes that designers will keep shopping. It’s a giant sales pitch on behalf of every decorator—telling homeowners why they should hire a designer to save them time, finding them better prices and exclusive goods, and preventing them from making costly mistakes.

Despite the challenges, educating would-be clients—and helping them find the right designer—is certainly a worthy goal. After all, for every homeowner out there who hires a decorator for a full-service project, there are hundreds more who don’t realize a designer could help them—and who have no sense of how much the resulting project would cost. (Santos says that Homepolish once conducted a survey to understand consumer expectations when it came to spending on their homes. The result? Respondents indicated that they expected a fully designed living room to cost $1,500—a figure so off-base that the company never released the survey’s findings.)

Santos says that ultimately, Freddie’s goal isn’t just to get jobs for designers, but rather to help reframe the way designers are perceived in the culture of home. “If you just see a designer as just an avenue to get a sofa, there’s not a lot [of opportunity] there in the long run, because technology will supplant it,” he says. “But if you see a designer like an artist or a therapist—there’s a reason why they haven’t been replaced by software. Away doesn’t sell luggage, they sell the promise of travel. I think the conversation in the industry needs to move from design being a functional and aesthetic exercise to it being a life experience.”

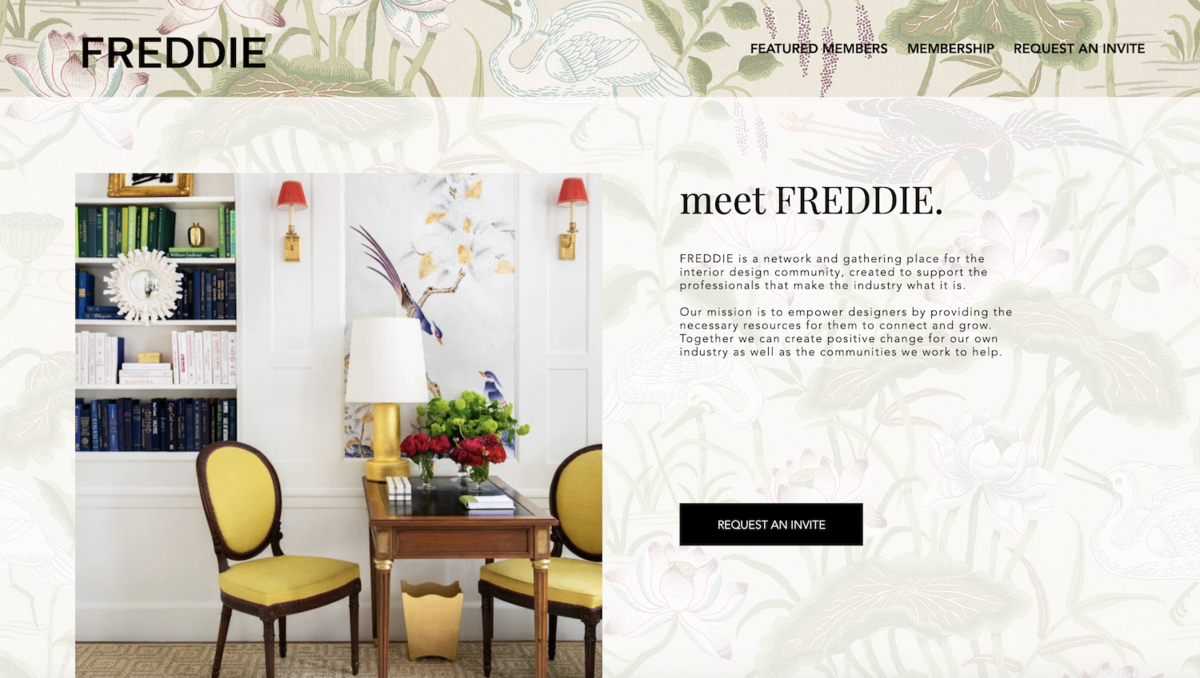

Homepage photo: A project by David Kaihoi, featured in a recent issue of Schumacher’s biannual magazine, Bulletin | Francesco Lagnese, courtesy of Schumacher