At the heart of the interior design business is a problem. It goes like this: Many middle-class homeowners love what designers do but can’t afford their services—meanwhile, the designers, no matter how talented or well known, can only take on so many clients, and thus their income has a “ceiling.”

That gulf between supply and demand has been around since the days of Elsie de Wolfe, and for just as long, there have been ideas on how to bridge it. Advice columns and decorating books were a kind of early solution: Designers could make money on their talent without having to schlep samples, and a wide range of readers could benefit from their knowledge. If you squint, HGTV operates on the same principle, only supercharged and twisted by the unreality of reality TV. Laurel & Wolf, Homepolish, Modsy? All tech-powered attempts to solve the same problem.

In recent years, often helped along by technology, designers have become increasingly entrepreneurial about finding new ways to scale. Some launch hourly consultation services on the side, remote or otherwise. Others develop an entirely different side firm for small projects, run by junior staffers. There are affiliate links, PDF floor plans, design retreats, brand deals, paid newsletter subscriptions, and blogs with programmatic advertising. Then there’s the “room in a box” concept.

There is no precise definition of “room in a box”—it’s a marketing catchphrase, not a scientific term. But it tends to refer to an offering whereby a designer creates a room in isolation, and customers can buy some or all of the product within it. If a comprehensive e-design service, with regular video calls and lots of customization, is on one end of the spectrum, the room in a box is usually on the other. It’s not hard to see why the idea appeals to designers: Create a room just the way you like it, sit back and wait for the cash to roll in.

The concept has a backstory. In the 1990s, Decorating Den debuted a room-in-a-box offering, selling sets of designer-curated furniture, accessories and art for as little as $3,800, marketing them under names like Brush Strokes. Surely they weren’t the first, and they were certainly far from the last—many designers would go on to develop similar concepts, including, notably, Los Angeles designer Windsor Smith. Then in 2018 and 2019, the industry saw a small flurry of room-in-a-box entrepreneurship with the launch of Florida designer Leta Austin Foster’s PREtty FABulous Rooms, and, on a larger scale, Kathryn M. Ireland’s The Perfect Room.

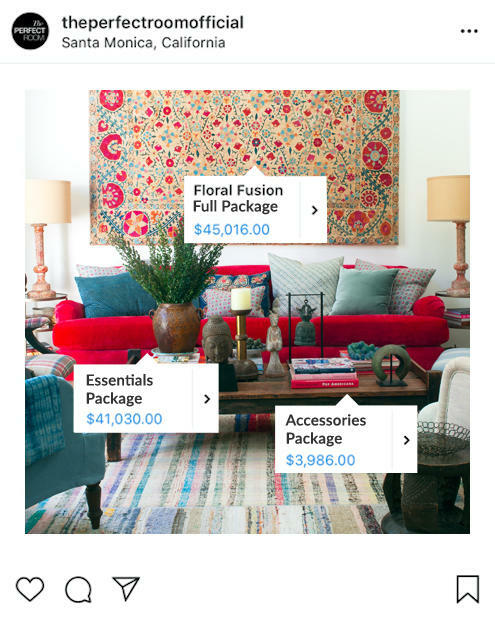

Foster’s was the classic room-in-a-box concept: She and her team created six design schemes and offered them online to customers starting at $35,000, all in. The Perfect Room was larger in scope, with a few unique twists. Ireland had corralled a murderers’ row of A-list design talent, including Robert Stilin, Timothy Corrigan, Robert Couturier, David Netto and Bunny Williams. Each provided images of rooms they had done for other clients (or themselves), along with shoppable links so that customers could replicate some or all of the look, a combination Ireland described as “Pinterest and 1stDibs in a blender.” In return, designers would get a commission on goods sold.

Though it was driven by 21st century technology, The Perfect Room was nothing if not an attempt to solve a perennial industry dilemma: “Having had many conversations with my fellow designers, there’s only one of us—people want you,” Ireland told Business of Home in early 2020. “How do you keep your business going when you want to retire?” She raised money to fund the project and hired Michael O’Neal, a CEO with tech bona fides.

But a year later, Ireland quietly shelved The Perfect Room. Windsor Smith’s room-in-a-box website now redirects to a real estate venture. And though Foster says PREtty FABulous Rooms hasn’t gone away entirely, her team has taken the website offline.

There’s context for each of these stories. Foster says the firm got busy with full-scale design projects during Covid and didn’t have the bandwidth for her online service. Ireland says that The Perfect Room kicked off a search for venture capital funding right at the start of the pandemic, and Silicon Valley was in no mood to write checks.

Still, it’s telling that the room-in-a-box concept has failed to produce any big success stories, and that its most high-profile recent incarnation didn’t achieve liftoff. One explanation may be that the concept of “democratizing” high-end design for the masses is fundamentally flawed, like Hermès selling $25 tote bags.

“It’s really hard when you’re at the high end of the business, trying to dumb it down,” says Ireland, reflecting on The Perfect Room’s challenges. “It can’t be available to everyone. That’s the whole point—it’s a luxury industry.”

Another is that the room-in-a-box approach may simply be out of step with the marketplace. Though it involves the work of a talented designer, the concept is basically a retail strategy. What customers are buying is product, artfully presented. In the 1990s, when great design was harder to come by and designers had exclusive access to unique resources, packaging the two was a compelling pitch. Now, in the age of Pinterest, Instagram and 1stDibs, anyone can see and buy anything. A pretty room isn’t enough anymore.

That dynamic is likely to become even more clear in the years ahead as AI gets better at generating beautiful rooms and making them shoppable. For clients, the value of hiring a designer will continue to shift toward the experiential side of the business: project management, personalization, problem solving and empathy. In other words, the human, difficult-to-scale stuff.

Fittingly, the design startup that has generated the most buzz in recent years is The Expert, a platform that focuses on the one-to-one, organic connection between designer and client, not a list of shoppable links. Yes, the company, founded in the thick of the pandemic, doesn’t entirely solve the scaling issue (you’re still trading time for money), and selling product is very much part of how The Expert has evolved. But it’s no accident that the platform has found success centering the design process, not the design result.

Maybe “the problem” will never really be solved, and maybe that’s OK. “I still think it’s a great idea, and I’m glad we tried it,” says Ireland of The Perfect Room. “But at the end of the day, it’s that personal connection with the client and the house that I enjoy.”