When we talk about race in the design industry, how do we talk about it? Mostly, in generalizations and the passive voice: “There is a lack of diversity.” “Black designers have been underrepresented.” “There is progress to be made.” And so on.

There are reasons for that. One is that speaking in generalities enables the comforting delusion of universal blamelessness, as though racial inequity is something that just kind of happens, like rain or traffic—as opposed to being the direct result of action (or inaction) by specific people. Another is that, while most will agree that there is a lack of diversity in the design industry, it's such a big, unwieldy problem that it's difficult to clearly define. We use unspecific language to cover our bases.

“There is a lack of diversity.” Obviously true, but how much of a lack? That’s hard to say. It’s difficult to run the numbers, so most people don’t bother. But some do.

Jomo Tariku is a Virginia-based furniture designer (he was born in Kenya to Ethiopian parents). His practice began in the early aughts, when he spent years developing pieces inspired by traditional African craft, run through the language of sleek, pared-down modernism. The work didn’t gain traction at first, and Tariku did what many creatives do: He got a day job. As a data scientist for the World Bank Group, he uses visualization tools to clearly present complex datasets, like comparisons of economic regulations in various countries or population growth on the African continent.

For much of his career, Tariku’s day job and creative endeavors never intersected. Then, in 2015, after his long hiatus from pursuing furniture design, one of his pieces was included in an anthology on contemporary African design. It ignited new interest in his work, and led to opportunities to enter the broader world of furniture design—markets, galleries, conferences and fairs.

What Tariku encountered was striking. At the World Bank and in the data visualization industry more broadly, the workforce was fairly diverse. In the furniture world, he was often the only Black person in the room. “Most Black designers have the experience of being the only one there or one of a handful of Black designers. I kept noticing it, and I started to say, ‘This is a weird industry!’” says Tariku. “When I go to data visualization conferences, relative to furniture, I don’t feel that. People come from all over. But you go to [Salone del Mobile in] Milan ... They estimated that more than 300,000 people went in 2017. I would say I saw a maximum of 20 people there who were Black.”

Encountering the same phenomenon again and again, Tariku began applying skills from his day job to look at the world of design. Rather than letting generalities about race and diversity stay general, he began collecting and organizing data. The methodology was blunt, simple and ingenious.

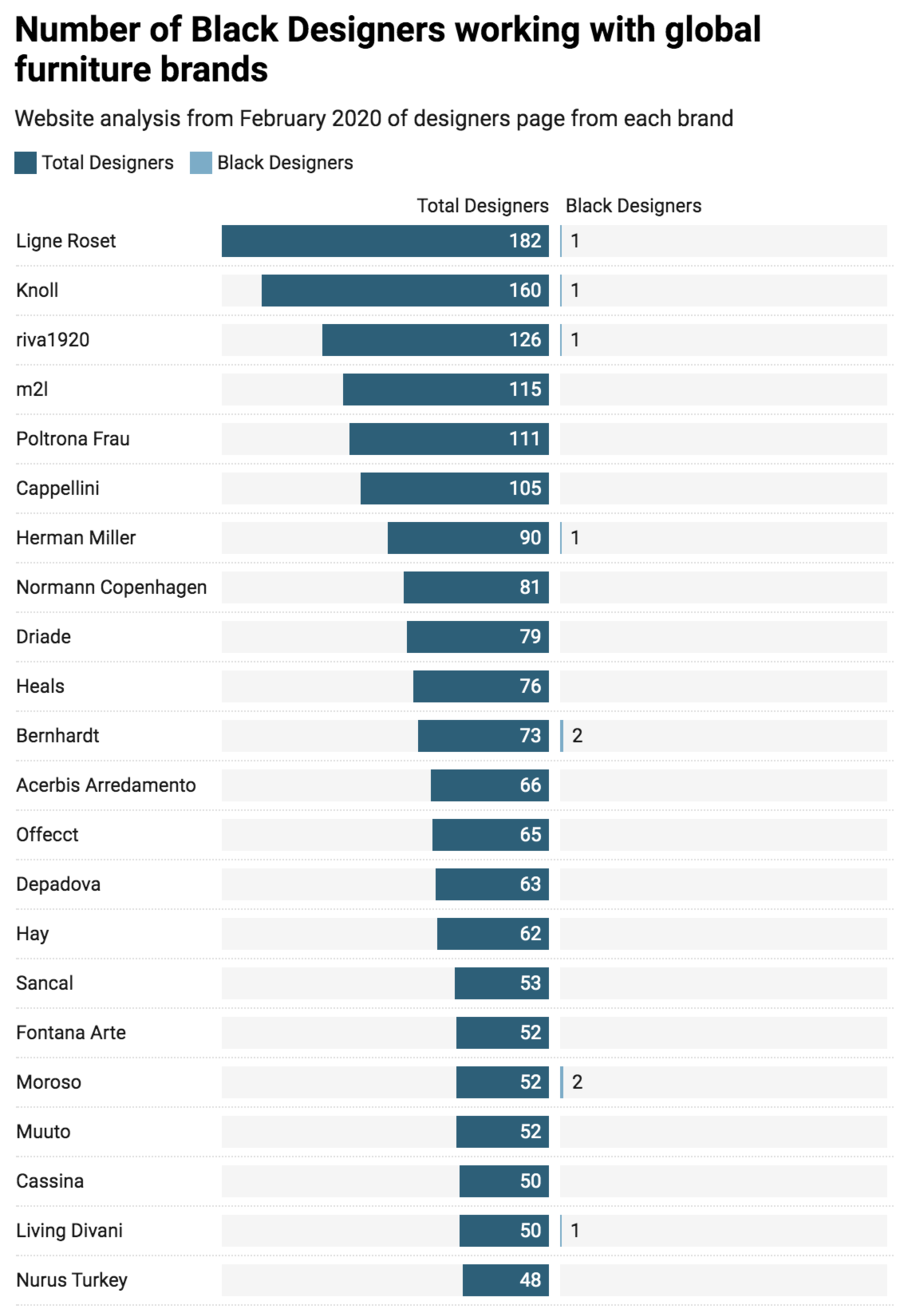

Tariku took a catalog published by Architonic, a widely-used Swiss product resource platform, and used it to identify over 150 of the world’s most noteworthy design-oriented furniture companies. Throughout 2019 and 2020, he periodically went to their websites and took screenshots of the pages where brands listed the designers they had collaborated with. Often, they posted pictures of these designers. Tariku simply counted how many Black people he saw.

When he was finished, the data presented a stark picture: Of 4,417 branded collections, 14 were with Black designers. That’s roughly one-third of 1 percent. (The full results are here).

By his own acknowledgement, Tariku’s study comes with qualifications. There are repetitions among companies (several designers worked with more than one furniture brand), so the data isn’t capturing 4,417 designers, but rather 4,417 instances of collaboration. And, as Tariku was capturing the data over an extended period of time, it’s possible that some of the numbers have changed, or that brands didn’t keep their websites current, or even that he passed over a designer. But there’s no missing the forest for the trees. “Is it the most accurate? I think it’s pretty decent,” he says. “Could I have missed one or two people? Yes. But is there a pattern? For sure.”

One of the challenges is that the dataset points to a total lack of representation, so it’s difficult to draw tidy conclusions or identify easy villains. One could point to the fact that Tariku found that Michigan-based furniture brand Herman Miller listed only one collaboration with a Black designer out of 90, or that Italian brand Riva 1920 featured only one out of 126. But in fact, the vast majority of furniture brands he looked at listed none at all. The highest number of collaborations a single brand had with a Black designer? Two.

American or international, small or large, the conclusion is the same: Most furniture brands collaborate almost exclusively with white designers, revealing an unmistakable systemic problem.

+ + +

The reasons for furniture’s racial homogeneity are complex and multifaceted. One contributing factor is the Eurocentricity of the industry itself. Many design-oriented furniture brands are European, and their choice of collaborators tends to reflect the demographics and sometimes the prejudices of their own countries (many European nations purposefully don’t count their populations by race, but broadly speaking, Europe is less diverse than America).

In a conversation with Boston-based curator and author Glenn Adamson at Dezeen’s Virtual Design Festival, Stephen Burks, a Black designer from Chicago, discussed his experiences going to Europe in the early 2000s. “There were only two or three American designers working in Europe when I first started. Not only was I American, but Europe very quickly reminded me that I was African American,” he says. “I remember one of the first articles written about me described me as ‘Tall like a basketballer and elegant like a jazz musician.’”

Even the framework of “design” itself, argues Burks, is a Western concept. “We look at the Western canon—the industrial revolution in Europe and America leading to the Bauhaus, leading to the idea that a designer can be in service of industry,” he told Adamson. “All of the products and ideas that we think about design don’t include the majority of the world and their cultural perspective.”

Another reason for the lack of representation is the academy. Design schools tend to have a lackluster track record in attracting students of color—by some estimates, as little as 6 percent of design school graduates are Black. Thus, the pool of young talent stays homogeneous, which leads to a homogeneous professional class.

It’s a phenomenon not lost on those inside of academia, both here and abroad. Earlier this year, renowned Dutch design school Design Academy Eindhoven posted a public mea culpa: “The Design Academy is not a diverse school. It does not accurately reflect the society it exists within, let alone the planet more broadly,” wrote members of the executive board. “We must do more, and do it now.”

John Dunnigan, a professor in RISD’s furniture design program, acknowledges the issue and says that he and his colleagues are also seeking to address the problem at the elite Providence, Rhode Island, design school. “This kind of thing is a serious concern; we understand that it’s a very white profession,” he says. “I make no excuses for the system, because it needs to be changed. … The industry depends on us [and] it’s not going to change until we change.”

Then, of course, there are the brands themselves. While a variety of factors can set the stage, ultimately it’s up to decision-makers at these companies to proactively seek out and work with Black designers.

Tariku completed his research in early 2020, before the killing of George Floyd ignited a firestorm of protest and a soul-searching national conversation about race. In the flurry of social media support for the Black Lives Matter movement that followed the protests, design brands across the spectrum posted messages of solidarity. Some had appeared on Tariku’s list.

When asked by Business of Home about their plans to take action and diversify their roster, most companies offered statements expressing both regret and a desire to do better in the future.

“As an organization, Herman Miller has long been committed to diversity and inclusion, but the past few weeks have opened our eyes, ears and hearts to how much more work we have to do,” wrote Herman Miller CEO Andi Owen. “We know we must do more to improve representation and opportunities for people of color in our industry. This isn’t a new problem—it has deep roots, and it won’t be solved overnight. We are focusing on two key areas. First, we are looking inward as Herman Miller Group needs to do a much better job of recruiting and hiring employees of color. Likewise, we must create more areas of opportunity and growth for our Black and Latinx employees. Our Herman Miller Group community and all of our brands—including HAY, DWR and Herman Miller—are equally committed to this work.”

Matt Manes, president of furniture distributor M2L, also acknowledged that his company needed to do more—and push its partners to do the same. “We have tended to look at our diversity internally as a small business and have built a team of different racial backgrounds, genders and orientations to create a dynamic community that can better serve our customers,” he wrote. “We realize we have to do better. The statistics about the extremely small number of Black designers represented in furniture companies, including M2L, are staggering. As a furniture distributor, we want to make a commitment not only to seek out new manufacturers with Black designers, but also actively push the manufacturers we currently represent into pursuing a diverse base of design talent.”

Whether these sentiments are followed by action—and a shift in the numbers—remains to be seen in the days, months and years ahead.

+ + +

Whatever the myriad causes that have led to the homogeneity of the furniture design world, it has a self-perpetuating and stultifying effect. The lack of well-known Black designers means a lack of visibility, which means many young Black creatives don’t have the chance to see themselves in the profession—a problem that feeds into itself. A dearth of Black furniture designers also creates a narrow band of style that others are expected to fit into. Tariku has experienced the latter firsthand, saying designers influenced by African craft are often expected to produce handmade one-of-a-kind objects of a certain style.

“That’s how Africa is defined: You can only do the handcrafted thing. Or the upcycling or the recycling. Then someone like me shows up, and the gallery representative or curator is like, ‘You don’t fit my mold,’” says Tariku. “A couple of my friends have said, ‘Why don’t you drop the “African” part, and you’ll be fine?’ My reply is, ‘Well, let the Scandinavians drop the “Scandinavian” part. Let Italians drop “Italian.”’ If they’re not, why is there a demand on people like me [to do the same]? There shouldn’t be.”

Untying the knot, obviously, will not be simple or quick. The changing of an entire system requires sustained effort from all parties involved. Universities must aggressively pursue attracting and retaining Black design students. Furniture brands will need to make good on their promises. None of this will happen easily or overnight.

However, Tariku’s study demonstrates that, while racial inequity in the furniture design industry is vast, it’s not unknowable. Hard data can cut through the vagueness of language and emotion to clearly present a problem. And only when a problem is clearly understood can it be truly addressed.

“You go to a panel discussion and people say, ‘We understand there are inclusion and diversity issues, especially around Black designers [doing] branded work for furniture companies,’ and everybody nods their head, as it’s so obvious,” says Tariku. “But no one has context. The context that’s missing are numbers.”

Homepage image: Shutterstock