Last week, Instagram feeds filled with black squares, part of an initiative called #BlackoutTuesday, which originated in the music industry and emphasized muting scheduled social media content in order to focus attention on the black voices using the platform.

Now, it’s time to fill that blank space.

This morning, the Black Interior Designers Network is launching a new fundraising campaign to raise awareness about how the industry can stand with black designers to create lasting change.

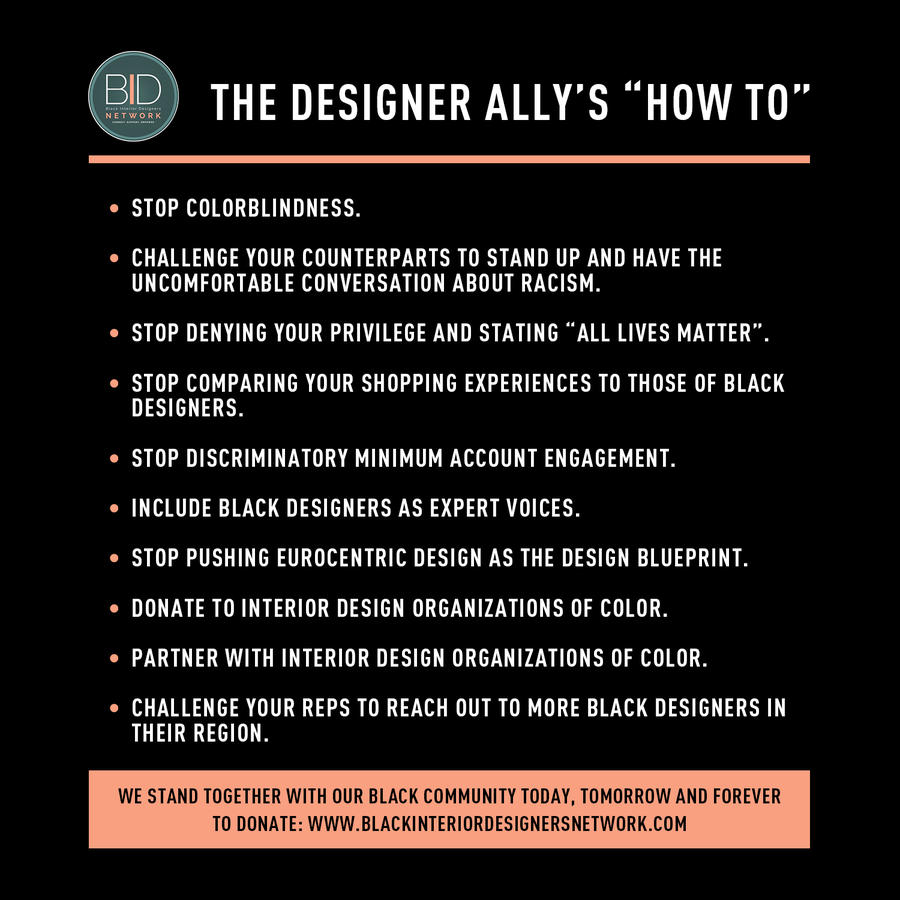

The initiative unfolds in two parts: The first is a graphic (shown here) that details how to be an ally to black designers, which industry members are encouraged to post on Instagram starting on Monday. The second is a call to donate to the organization, which spotlights the work of black designers in addition to providing resources and business development opportunities. Donations will support the BIDN’s operations and initiatives—the organization also plans to make its own donation to the NAACP.

The BIDN was founded 10 years ago by Kimberly Ward, a designer and blogger who wanted to highlight and foster business opportunities for black designers. When she passed away in 2017, her protégé, Denver-based designer Keia McSwain, became the organization’s president. “Kim started this network to establish something that embraced black designers, regardless of their years of experience or their portfolio,” says McSwain. “She wanted to create opportunities and facilitate growth. Back in 2010, she was basically begging to be seen or heard. And it’s 2020, she’s gone, and here I am having the same conversation.”

With this initiative, McSwain hopes that narrative will begin to change. “At some point we want to stop having panel discussions about diversity and inclusion,” she says. “We want to have conversations about how diversity and inclusion changed in the industry, and where we have come—the long road it took to get here, and the fact that we finally made it. That’s the conversation we want to have.”

BOH caught up with McSwain and BIDN chief development officer Alison Harold to break down the initiative’s 10 steps to becoming an ally in the design industry. “Our biggest call to action is to ask the industry to take a moment to educate themselves, look at their own policies, and ask, ‘How have my policies and the practices of the industry at large impacted designers of color, and African American designers specifically?’ And then to move to make a change,” says Harold. “It may be uncomfortable. It is understanding that it will come with sacrifice, but also that it will be good for the industry as a whole.”

Stop colorblindness.

“I don’t want you to pretend that you don’t see color, because we all know you do see color,” says McSwain. “I want you to see my color. I want you to respect my color, I want you to honor my color, and I want you to help elevate me to positions that we both know my color in some instances may hold me back from.”

Challenge your counterparts to stand up and have the uncomfortable conversation about racism.

Start by asking yourself tough questions—but also by holding your colleagues accountable. “Think about that low-key racist person you know that’s said some shady stuff, but you let it go because they’re really nice and they don’t lean that far right,” says McSwain. “I [recently] told a friend, ‘If you confront your friends who are liberal but racist anyway, you make them look at themselves.’ [It’s about] holding other people accountable—including in the workplace.”

Stop denying your privilege and stating, ‘All lives matter.’

“All lives can’t matter until black lives matter,” says McSwain. “Saying, ‘All lives matter’ is the ‘but’ followed by an ellipses. It’s like saying, ‘I’m not racist, but …’ Pro-black does not mean anti-white. We just want you to recognize that systemic racism started with slavery and has trickled down, so that when we go out and compete in the world, we’re still 10 steps behind. There’s no real urge or willingness to see us succeed. Now, it happens. We do it because we are resilient and determined—but there are hurdles!”

Stop comparing your shopping experiences to those of black designers.

As black designers have come forward with stories of discrimination, some have experienced others trying to explain away the mistreatment as a misunderstanding. “They’ll say, ‘I work with them all the time and they’re pretty nice,’” says McSwain. “When there’s a pedophile on the loose, no one’s standing behind that person trying to protect them, or saying, ‘We just don’t want to ruffle any feathers.’ But there’s this attitude of, ‘When she’s not being racist, she’s a pretty nice person—she bought me lunch two weeks ago when I left my wallet at home.’”

For many black designers, there’s a sense that even if discriminatory behavior is reported, that person won’t face any consequences. “They know to some degree that they’re not going to be punished for it. Maybe someone asks, ‘What happened with you and this designer?’ But that’s it—versus, ‘I’m going to fire you because we don’t want you treating customers like that,’” says McSwain. “We want the industry as a whole to be anti-racist. Be against it.”

Stop discriminatory minimum account engagement.

Minimum opening orders can keep a vendor’s products out of reach, especially for designers just starting their careers or trying to grow the scope of their projects. Many black designers, both in the Network and outside of it, have shared stories of being shut out from certain vendors due to minimum-order rules that have been waived for white designers. “We know everything’s not about race, but do what you should to make sure my experience is just as superb as if a white designer came to open an account with you,” says McSwain.

The country’s long history of systemic racism plays a role here, too. “When you think about the history of the African American community’s access to credit and how that limits them—I might not come with the same credit history or buying potential on paper, but it’s not because I don’t have clients or I don’t pay my bills on time,” says Harold. “If there are limited opportunities for me to access the clients [and] jobs that would help me meet minimum purchase requirements, how will I ever have access to that product? You may say, ‘Then maybe it’s not for you,’ but we want to make sure [the double standard] changes and that there’s better transparency or alternative opportunities [to access product] through purchasing groups.”

That line of thinking extends to all facets of design businesses, from designer collaborations to internal policies. “Challenge yourself to think about the practices you have in place and what impact they might have on a community of color,” she adds. “When you look at your industry or profession and say, ‘There’s really low representation,’ ask why. Don’t assume that [black designers] aren’t aware of your product or aren’t able to afford it—those are the assumptions that have historically been made. If you’re not looking at your policies and asking questions, it suggests you’re turning a blind eye to what may or may not be a problem.”

Include black designers as expert voices.

“The black designer’s voice is never prioritized: There’s a sprinkle here or there, but if you think about it, the real market or conference keynote—I’ve never seen any keynote [by a person of color],” says McSwain. “The Network’s goal is to engage and push you out there—push resources, and push you up to the same table.”

She also notes that designers want to have conversations about their work—a privilege far more often afforded to white designers. “Being really great at what we do but still having to deal with things that are built to hold us back—and having to keep talking about it—is hard,” she says. “Talk to us about how to properly hang a panel or the right fabric to use in this room and why we like the colors we do. I don’t want to keep talking about what it’s like to go into a showroom and be ignored or walking up to a chair and the first thing [showroom staff] say is, ‘That chair is $4,500.’”

When it comes to design media, it’s a climate that has led many black designers to avoid pitching their projects to publications altogether—or that has led some to seriously consider removing their portraits from their websites. “There are some designers looking at this from the point of view of, ‘I don’t pitch or share—I would rather post my stuff all over Instagram because I know they’re not going to pick it up because I’m a black designer.’”

Stop pushing Eurocentric design as the design blueprint.

What’s long been billed as inspiration in the design industry is actually rampant appropriation. “It’s pulling from cultures and then either not acknowledging the significance and origins of those things, or whitewashing it to make it feel more comfortable to your customer base,” says Harold. “We look at it and shake our heads, but then we accept it because it has become the norm. There was not a moment in time when we were coming together collectively to say it has to stop, but this is that moment.”

In the case of shelter magazines, McSwain says that even editors have acknowledged a tendency to publish a certain ruffle-no-feathers aesthetic. “They’re saying, ‘Yes, we are seeing a lot of the same cookie-cutter design.’ But why is that? Do they want to stay safe? Do they not want to pop?” she asks. “There’s this whole aesthetic that has taken over the industry, and nobody is talking to black designers about its culture and history and where it comes from. It’s like, ‘We’re going to sell Kuba cloth wallpaper now and find some way to market it—but don’t call it African or tribal, call it worldly.’ No, call it what it is. It’s disheartening for a lot of black designers to see our culture come to life in so many spaces but its origins are given no recognition.”

Donate to interior design organizations of color.

The BIDN has set a $250,000 fundraising goal for this campaign—funding that will bring sustainability for the 10-year-old nonprofit. “For so many years, we’ve made it work by working out of our own pockets,” says McSwain. “But if people care and want to see us grow, resources need to be poured into the black community. What you’re saying [when you donate] is that you want a competitive workplace for everybody.”

The campaign, says Harold, will fund resources to expand opportunities for the designers in the network. There are other benefits, as well. “We understand the power behind money and influence,” she says. “If larger brands stand up beside us, it helps to show value and demonstrates that we no longer have to jump through hoops to earn a place.”

In addition to hosting its 10th annual conference in July 2021 (it was postponed from this year due to the coronavirus), the BIDN has several new initiatives in the works, including online programming, community events and urban renewal projects. The organization will also be developing workshops about inclusivity and diversity for industry workplaces. “We are really adamant about getting into workplaces to do these training courses,” says McSwain. “We want to ask, ‘What are some things you want to say, but you’re not sure if that’s the right thing to say?’ We think that’s important. That’s where all this starts—with a conversation.”

Partner with interior design organizations of color.

“We’re looking for partners that will really invest in our mission—to help us grow and to educate their team through us,” says McSwain. “There are a ton of ways to partner with us—as a media partner, a partner that works with us to provide buying power to our members, a partner that invests financially in the network, or to bring in some black designers to get your business right where it comes to diversity and inclusion. Partners should understand that there’s power in where we put that money and how we utilize it. In order for us to sustain, grow and keep fighting for the same resources, opportunities and visibility, we have to have partners.”

Challenge your reps to reach out to more black designers in their region.

“When I was working in sales, I was taught that you want to make people feel like you want to work with them,” says McSwain. But in the design industry, many vendors don’t operate that way. “Part of it is because reps are not held responsible for the black designers they’re not reaching out to. There should be some black designers that you’re reaching out to—and you should be starting the conversation with [an attitude of], ‘I’m willing to work with you,’ not, ‘Can you meet this financial minimum?’”

Studies show that companies have better profit margins after actively eliminating racial biases from business practices, says Harold. “There’s an economic case that can be made for why it makes sense—so when that’s still not happening, it tells me that it goes deeper than that.”

The broader goal of BIDN’s allyship campaign is to finally turn talk into change, inside and out of the industry. “Michel Boyd said that we’re all George Floyd in some aspects of our lives—the industry will put its knee on your neck if you allow them to,” says McSwain. “We are looking to create a setting for talking about ways that we can maneuver this whole diversity and inclusion thing, and how we can minimize [the need] to keep talking about it—because, like I said, we don’t want that to be the conversation. We’re so much more than diversity and inclusion.”

“Everybody can do something,” adds Harold. “Just keep asking yourself what you can do—and be willing to push yourself outside your comfort level.”

Click here to donate to the Black Interior Designer Network’s campaign.

Homepage photo: Attendees at the BIDN's annual conference in 2019 | Charles Dante