There’s a concept in artificial intelligence called “the singularity.” It refers to the idea that AI will one day be able to reproduce and improve upon itself at increasingly rapid speeds, resulting in a computerized brain exponentially more powerful than human intelligence, capable of transforming civilization as we know it. Cue either a robot-enabled utopia or a hellish cyber-apocalypse, depending on your faith in technology.

Some scholars are confident the singularity is only a matter of time. Others say it’s pure science fiction. For the time being, let’s leave the issue to the Ph.D.s and focus on a few simpler questions. Forget whether a computer will ever be able to design a smarter computer—will a computer ever be able to design an elegant, midcentury-inspired living room? Are we due for an interior design singularity? And if we are, will human designers become obsolete?

For most designers, artificial intelligence is probably low on the list of things to worry about, well below where the next client is coming from or even the office Wi-Fi password. AI often feels like a remote concern—if you keep up with the news, you’re probably aware that, somewhere out there in the world, AI is drawing pictures, writing poetry and playing chess, but it’s not a conscious part of the daily life of a designer. Behind the scenes, however, that’s changing.

A common misconception about “artificial intelligence” is that the term refers to a computer that replicates human behavior—like Data from Star Trek, or (more ominously) HAL from 2001: A Space Odyssey. A much more common version of AI is simply throwing the computational force of an algorithm at a single task. If you have a computer analyze 10,000 hours of traffic on the Brooklyn Bridge, the computer can get pretty good at predicting traffic on the Brooklyn Bridge. That’s artificial intelligence.

In the design world, AI is already popping up left and right. It powers product design, rendering software, and (most of all) online commerce. “Visual search” is a particularly big growth area for AI in design. Houzz, among other retailers, now allows users to upload pictures of inspiration images, which are then analyzed via an algorithm and turned into product recommendations. (Like that sofa on the cover of Elle Decor? Here’s one just like it!) Discount furnishings brand Coleman Furniture, which introduced a similar tool this year, told Furniture Today that it improved its conversion rate by over 600 percent. AI is not only here—it’s paying off.

You’ll notice a thread to the above examples: These are tools designed to make work easier for humans, not to replace them. A recurring theme of the rhetoric around AI is that it will primarily be used for tasks that are boring or inefficient for people to do. There’s an ethical element to that—it’s bad PR to launch a product specifically designed to take someone’s job. However, that concern alone is hardly what holds developers back. There are also technical limitations at play.

While AI is very good at solving data-driven problems with clear parameters, mastering complicated, creative work that combines different skill sets (like, say, interior design) is another matter. Add to that the sheer volume of data involved—from the millions of products available on the market, to to the complexities of working within an existing floor plan and the task of generating a design that fits its owner like a glove—and it's clear why even designing a simple room is a computational challenge.

That’s why it’s relatively rare to see entrepreneurs apply AI to the “generative” or creative part of interior design. Even forward-leaning e-design platforms like Havenly and Modsy use machine learning more as a tool to aid human designers than as a soup-to-nuts solution. Both platforms use AI tools to speed up design—for example, presenting their designers with 10 algorithmically chosen sofa options instead of 100—but neither has replaced its team of designers with the technology.

“Our perspective is that [the highest percentage machine learning can execute a design] is maybe 60 or 80 percent. It’s less than 100,” Havenly CEO Lee Mayer tells Business of Home. “There’s always going to be a place for a human there.”

Another challenge of applying AI to design has to do with the way that it is “trained.” It’s relatively simple to show a computer traffic footage—it’s easy to obtain, and easy to break down into simple variables (traffic is either fast, which is good, or slow, which is bad). By contrast, breaking down design projects into data and feeding them into an algorithm is complicated. Every afternoon, thousands of cars go over the Brooklyn Bridge. But on a given day, maybe only one person buys a particular console table and puts it in their living room. It’s hard for a machine to learn from a sample size that small.

“Because of the amount of items, the amount of variability and the bespoke nature of interior design, you get a lot of ‘thin’ data,” says Mayer. “You get a lot of noise in the signal. Just because you have two people who looked like Fred that liked the ugly red lamp doesn’t mean Fred’s going to like it.”

Put simply: While the rise of artificial intelligence is impacting design already, it’s no simple matter to program an algorithm to gracefully blend old and new in a south-facing living room. But that doesn’t mean people aren’t trying.

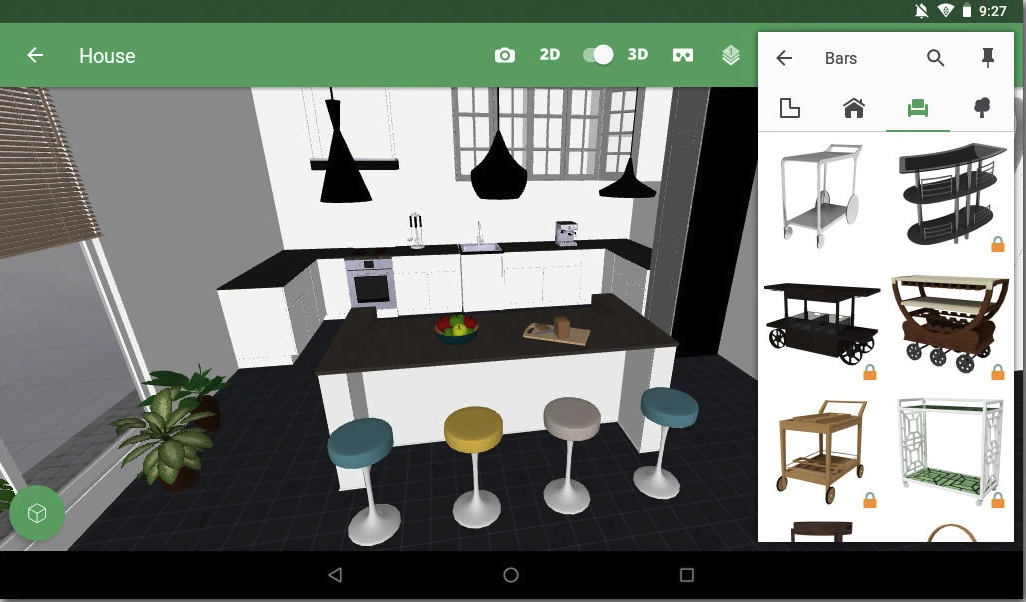

One of the companies on the front lines of digitizing design is Planner 5D, a startup based out of Lithuania that gives users a suite of simple tools to create 2D and 3D floor plans. The premise is, essentially: Use us to design your dream home. The company claims it has over 64 million users who have created more than 300 million projects—that’s almost one digital home for every person in America.

Right now, Planner 5D makes money with a “freemium” model, giving away a set of tools for free, then charging users for upgraded features. However, the company is well-positioned to grow in a variety of different directions. After all, if millions of people are using your software to design a dream home, it’s not a leap to imagine them making purchases, hiring contractors or securing financing while they’re on your site. Getting there will take more development, a good deal of it powered by AI.

“In home renovation and interior design, there’s not a huge amount of cutting-edge technology,” CEO Andrey Ustyugov tells BOH. “That’s what drives us. We’re a hard-core engineering team, a bunch of AI guys, a bunch of developers, and we are really interested in bringing something cutting-edge to the industry.”

The first way that Ustyugov’s company uses AI is at the start of the design process. Planner 5D has a (paid) uploader tool that will take a user’s 2D floor plan and turn it into a manipulatable model. That sounds simple, but it’s no small act of translation to take a JPEG and turn it into a digital model. I tried the tool using a crudely drawn floor plan I had found online, and the result felt almost like a magic trick—a few minutes after uploading the image, I could play around with a fairly accurate 3D version of my fake house, easily adding furniture and changing wall colors.

The company is also rolling out software that will enable similar results using a lidar scan from a smartphone. (In that, Planner 5D is not alone—Modsy has developed a similar tool that works using a smartphone camera.) All of it, says Ustyugov, is powered by AI, with technology making algorithmically informed “guesses” to fill in the blanks and generate a workable model.

That’s the input side—capturing the client’s home in digital form. The next big hurdle is to use artificial intelligence to fill it with furnishings. Interestingly, Ustyugov says that his team first explored AI-generated interior design simply as a way to hold people’s attention. “The majority of our users are not willing to spend any amount of time or inspiration to create designs,” he says. “They’re really there just to get the design.”

The Planner 5D team is currently developing Auto Furnishing, a tool that will take a floor plan, add input from the user (“I have two kids and a dog, and I like modern style,” for example), and create an algorithmically generated design scheme. This would, in essence, be a version of the interior design singularity—you really could tell a computer something vague like, “I want a south-facing living room that gracefully blends old and new” and get a rendering.

Of course, the devil is in the details. Getting it right requires a complicated blend of hard-coded rules—light switches shouldn’t be covered by doors, for example—with data taken from Planner 5D’s vast trove of projects. In that regard, the company has a leg up on the competition. As its users have generated 300 million digital dream homes, they’ve also provided the data that will help power Planner 5D’s artificial intelligence.

Auto Furnishing isn’t quite ready for public consumption. That’s partially an issue of server bandwidth; the process takes a lot of computational power, and user overload could crash the Planner 5D system. That aside, Ustyugov’s team is still working on fine-tuning some of the kinks before unveiling the technology later this year.

In a test version that Ustyugov showed me, Auto Furnishing quickly generated several design schemes for a small bedroom. The system showed clear signs of sophistication—beds and armoires were all in the right place, and when he selected a stand-alone fireplace to drop in, the system helpfully suggested it go along the perimeter of the room. However, it could also generate quirky results. One version of the room was filled with chairs—a result, he says, of the fact that when amateur designers use Planner 5D’s free tool, they like to try to fit as many chairs into a room as possible, which confuses the algorithm.

The main challenge the tool will need to overcome is how to properly implement the scoring system that distinguishes a good design from a bad one. It’s a complicated problem, Ustyugov explains, simply because “good design” is subjective. Even with a lot of hard-coded rules, it’s difficult for an algorithm to recognize a practical room, let alone a beautiful one.

However, an exquisitely beautiful interior isn’t exactly what Ustyugov is going for, anyway. The goal of the tool is not to unseat the AD100, but to provide a baseline for amateurs. “When you have a very specific task set, like, ‘I want to have a big living room for a family of four with modern design in this budget,’ AI is actually able to solve this problem better than bad designers on the market,” he says. “But usually, AI still has some problems when you need to create something really unique.”

The progress Ustyugov and his team have made so far is impressive; however, it’s too soon to know where Planner 5D’s algorithm-powered interior design will go. If it doesn’t end up yielding an industry-changing result, the company wouldn’t be entirely alone—other startups have experimented with interior design algorithms and hit a wall. Leaperr is a prime example.

Founded in 2017 by Tel Aviv–based entrepreneur Gil Admoni, Leaperr set out to tackle the same challenge as many tech companies in the home space: The average consumer is terrible at design; if you’re able to do it for them cheaply, you can make a decent margin by selling the furniture (or by selling the software to a brand who will use it the same way).

Like Ustyugov, Admoni was drawn to a tech-based approach. But Leaperr didn’t have a treasure trove of user-generated floor plans to draw from. He took a different tack, one based around computer vision—a technology in which an algorithm is trained to “look” at photos and recognize objects. Admoni and a small team developed an algorithm and began feeding it hundreds of thousands of pictures. The result was a program that not only knew what a sofa was, but had a pretty good idea of where people liked to put one in a room.

The appeal of Leaperr was its simple, blunt-force approach to AI-generated design. Rather than attempt to translate existing floor plans into a 3D model, then ask users to tweak that model, Admoni’s creation worked entirely with static 2D photos. The algorithm was a bit like a designer who has speed-read every issue of Architectural Digest, then worked with clients by taking pictures of their rooms, cutting them up and re-collaging them to look more like AD.

However, the same thing that made Leaperr a clever tool also created problems. Because Admoni’s team was working with 2D photos, it was difficult for the algorithm to guess the dimensions of a room correctly. If a sofa was blocking a fireplace in the source image, Leaperr didn’t know the fireplace was there.

The program also suffered from another big problem: The final product simply didn’t look right. While the algorithm could perform the impressive task of stripping away furnishings from a static photo and replacing them with a new design, the resulting image was just a little off. The renderings didn’t look like the kind of professional design photos that would prime a customer to buy. In details where the algorithm was unsure, the photos were blurry, watery, even a little surreal.

“It was 95 percent there, but with a static image, it can’t be 95 percent OK,” says Admoni. “If you’re going into a meeting wearing a suit that has a small coffee stain on it, it’s 95 percent clean, but it’s still a disaster. With something like this, it’s black-and-white.”

However, even these issues might have been solved with another 18 months of development time. What ultimately sunk Leaperr wasn’t a technical issue but a more pedestrian conundrum for startups: They couldn’t secure investors without an impressive prototype, and they couldn’t finish an impressive prototype without investment money. “We ended up hearing two things: Show us the technology works and then we’ll invest in you, or bring us customers who believe the technology works, and we’ll invest in you,” he says. “We ran with it for almost two years, but we decided to stop.”

Ustyugov is confident that Planner 5D will debut AI tools that wow the average user. And Admoni is confident that even though Leaperr didn’t work out, someone will come along and solve the same problem. The notion that an algorithm can design a decent room, they believe, is a matter of when, not if.

Interestingly, both suggested that the technology would mostly help designers—not put vast numbers of them out of business. While this line of thought can feel like PR spin, I’m inclined to agree. For one, the technology is still a ways off. A good designer can easily out-design most of what’s available on the market today. At least so far, advances in AI mainly threaten mediocre designers or those whose roles narrowly confine their skills (if you’re doing anonymous e-design for a major retailer, take note).

And while the advantages of using AI tools are sometimes overhyped, it’s not hard to see the appeal of handing off grinding tasks to an algorithm. Ustyugov says that Planner 5D is used by designers as a presentation tool—imagine being on a video call with a client and having the ability to easily tweak a rendering on the fly without having to painstakingly redraw it.

The other obvious practical impediment to AI taking jobs is simply that interior design is a lot more than just generating a beautiful image. Until an algorithm can both create a gorgeous design scheme and make sure that the tile guy shows up on time, good designers’ careers are safe. But even if, far into the future, an entrepreneur comes along and builds a machine-powered tool that can somehow generate and install an AD100 room, it’s not entirely clear that it would upend the design industry, either.

One of the paradoxes of artificial intelligence is that while it uses technology to achieve impressive results, in the end, those results are judged and valued by a human. For something like traffic on the Brooklyn Bridge, that’s fairly simple. Slow equals bad. Fast equals good. For something as nuanced and emotional as the design of a home, what’s valuable is far more complex. Does a client fall in love with a chair because it fills the right space in their floor plan, or because they had a great conversation with the artisan who made it? AI can make only one of those things happen. A designer can do both.

Homepage image: Courtesy of Havenly