It’s hard to think of a decorator more associated with “traditional” than Sister Parish, whose use of striped ticking, floral chintzes, whitewashed antiques and patchwork quilts is widely credited with launching American country style into the spotlight by the 1960s. Funny, then, that in recent conversations with Parish’s great-granddaughter Eliza Crater Harris, the topics were decidedly 21st century: Instagram Live, e-commerce, and even transparent pricing. Crater Harris was well aware of the potential irony. “It may not be expected of us to embrace contemporary design dialogues, but in fact Sister was someone who loved change,” she says. “We often ask ourselves, What would Sister do?”

“We” is Sister Parish Design, a fabric brand founded in 2000 by Susan Crater, Crater Harris’s mother (and Parish’s granddaughter). The family connections go deeper. At the time, Crater had just finished collaborating with her mother, (Parish’s daughter) Apple Bartlett, on a book about the legendary decorator. From that experience sprang another idea: Why not resurrect some of the prints Parish and her business partner Albert Hadley had created for private clients? “I think it was kismet—which was also the name of one of our prints,” says Crater. “Launching the firm was about not wanting the Parish-Hadley legacy to die. What’s better than bringing the prints they did for their private clients into the marketplace? Otherwise, people might not have ever seen them again.”

What originally started as a historical rescue mission has become a much more forward-looking enterprise, a process hastened by the 2018 appointment of Crater Harris—an interior designer who previously worked with Markham Roberts—as creative director of the brand. I visited Crater’s home in Bedford, New York, this March, just before the coronavirus pandemic triggered nationwide shutdowns; as I sat down with all three generations of the Sister Parish legacy, it was clear that they were brimming with plans for the brand—from new patterns and colorways to transparent pricing and plans for street-level retail—and also that they weren’t planning to modernize Sister Parish Design at a hesitant, one-step-a-time pace. This was a confident stride into what the family sees as the future of design. And if they have to brush up against a few “traditional” industry taboos to get there?

“If we are really listening to Sister, then our brand should not be an altar to the past,” says Crater Harris. “[It should be] a design studio concerned with how decorators work and design today, and how people live today.”

In 1933, a 23-year-old Sister Parish launched her design firm, finding early clients in friends who admired the unique sensibility she had deployed in her own home, in Far Hills, New Jersey. Nearly three decades later, she met the young Hadley while working on the Kennedy White House, and the pair founded Parish-Hadley Associates in 1964. Their work and style would dominate American decorating in the coming decades, and they continued to work together until Parish’s death in 1994, all the while nurturing the next generation of great American designers. Like the push-and-pull between history and innovation the brand faces today, the Parish-Hadley relationship was often one of opposites attracting. Parish was known for her floral, feminine approach to decorating; Hadley was a modernist who prized an edited, architectural look. That yin-and-yang energy propelled their work to greatness, with a client list that read like the era’s who’s who: Astor, Getty, Vanderbilt, Whitney, Paley, Mellon, Rockefeller. “She wanted to hire someone to take over. She wanted to retire,” Hadley told The New York Times in 1996. “Thirty-two years later, we never retired. We had a marvelous relationship.”

The Sister Parish story, then, is Hadley’s too. Indeed, the archives that inspire the company’s patterns are a mix of textiles Parish collected on her travels and Hadley’s original designs. That said, there are few exact reproductions in the line; each pattern has been updated gently to resonate today. “We're not just resurrecting these textiles, we're also refining them,” says Crater Harris.

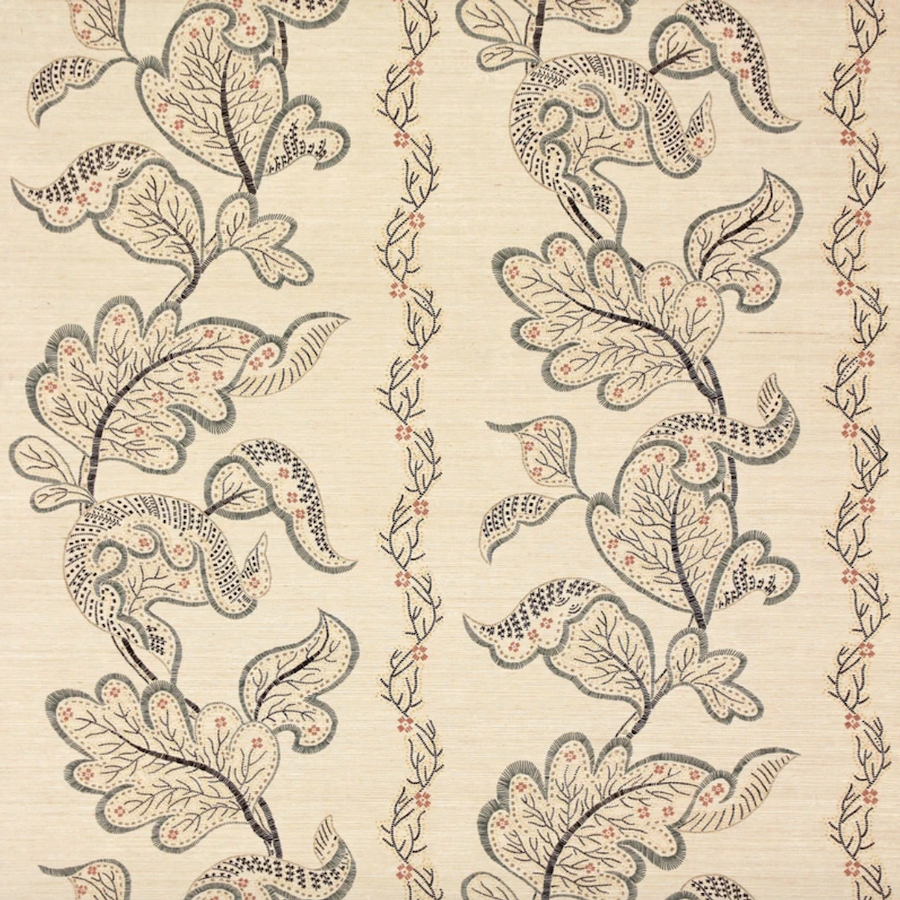

The rebirth of a pattern called Sintra perfectly illustrates the Sister Parish Design ethos—a tree of life pattern on a piece of quillwork in the Parish-Hadley offices that the two designers would ultimately turn into a hand-screened textile for curtains in Brooke Astor’s “Money Room.” (So called because it was where she sat to write checks for various charities.) “Albert designed Sintra from a piece of quillwork, but now we're printing Sintra on a piece of grass cloth,” says Crater Harris. “And the colors I've chosen for Sintra might not have been colors he would have chosen or that Brooke would have wanted, but we’re moving forward to serve the designers and clients of today.”

Walking that tightrope balance between paying homage to a storied legacy and embracing the seismic changes that have swept the industry—both aesthetically and in how designers shop—is no easy feat. Crater says that her daughter’s experience as a designer has shaped the company’s vision as it positions itself for the future, unspooling some of the more traditional ways of doing business in favor of an approach that reflects the way young designers want to interact with brands today.

The most notable shift came earlier this month with the launch of a new website. “We were working on updating our site pre-COVID, but the challenges of the last few months definitely accelerated the need for our company to offer more utility for the design trade online,” says Crater Harris.

The website also reflects a shift in business strategy, including sample fulfillment, listed prices, and the ability to transact online. “The new site makes it easier to shop Sister Parish fabrics, wallcoverings, and home accessories on your time, with better inquiry abilities for quicker responses from our team—all in an effort to untether our clients’ creative visions from an analog, 9-to-5 approach to designing,” says Crater Harris. “Adding pricing to our site is really just one of many other additions that makes it easier for our clients to do their work, and to shop as they please.”

Posting pricing can be seen as a challenge to the showroom model, but Sister Parish designs are still represented in 10 showrooms across the country, in addition to its international representation. Instead of taking business away from showrooms, Crater and Crater Harris see their new site as turbocharged lead generation for their partners, delivering qualified customers to the showrooms while still allowing the brand to connect with design enthusiasts who love the Sister Parish story.

“COVID clarified our need for online support on many different levels, from e-marketing, to a better capturing of client interest, to providing additional support to all of our showrooms,” said Crater Harris last week when asked how the sudden global shift had altered the family’s business plans. “We feel confident that this investment in our digital space will result in serious sales growth for our showroom representatives around the country and internationally. The world has changed rapidly, and this idea that a trade company that is represented at a showroom should not have an online presence is over, and our amazing showroom partners around the country understand that our ability to create energy online directly supports growing their leads and sales.”

The company did recently exit the John Rosselli showroom in New York, though not because of any disagreements about distribution. Last year, the company brought its sampling operations in-house, operating out of a studio in Bedford; for now, the studio will manage order fulfillment in the New York territory, as well. Though the pandemic has delayed the company’s plans, the next move for Sister Parish Design will be a street-level flagship in Manhattan, which they hope to open in 2021.

Like transparent pricing, street-level retail is part of the company’s emphasis on tapping into the enthusiasm of a new generation of traditionalists—the “grandmillennials,” if you will. The term, coined last September by House Beautiful, is associated with a love of ruffled florals, needlepoint pillows, and all things wicker among young people in their 20s and 30s, and hearkens unapologetically to the Sister Parish aesthetic.

It’s also a label that neatly captures the passions of a certain group of devotees that had been interacting with Crater Harris in the brand’s Instagram feed. “Our brand has connected with the hearts of a new, younger audience that is highly engaged with us on social media,” says Crater Harris of the excitement around the Sister Parish look among a group of young people perhaps not quite ready to hire a decorator or order custom drapery. When it went live, the site featured new ways for these fans, young and old alike, to access and interact with the brand: an online shop with hats in Sister Parish fabrics that sold out almost overnight; a selection of pillows and table linens; and a collection of spongeware plates, bowls and pitchers. A campaign featuring the tabletop products and two new fabric patterns was remotely styled (and shot on an iPhone) by tastemaker, stylist and editor Mieke ten Have in a COVID-era creative partnership brokered by strategist and consultant Sean Yashar, who felt that ten Have, like Crater Harris herself, uniquely embodied the grandmillennial sensibility.

Fabrics and wallcoverings will remain the heart and soul of Sister Parish Design as the company forges ahead—Crater Harris sees the foray into home products not as a push to enter a new market, but rather as a service to an already-existing audience eager to be part of the conversation. “Based on feedback [from our followers], we felt a responsibility to connect with them more deeply, but until recently, our product offerings were trade-only,” she explains. “With the site relaunch, we have also invested in a more diversified home accessories collection specifically to speak to our growing ‘grandmillennial’ audience that wants access to the Sister Parish lifestyle through tabletop, linens, pillows and apparel.”

A new storytelling initiative, “Tell A Sister”—Instagram Live conversations between Crater Harris and like-minded creatives that are then recapped in a bloglike format—also tap into the burgeoning passion online for that Sister Parish ethos. “My great-grandmother really believed in a beautifully designed home, but also that that was really just a backdrop for a full life—a life filled with kids and dogs and a career,” she says. “I see this series as a way to connect with our clients and our community, bringing together designers to talk about those things.”

For all of the company’s bold moves, much of its business model—and core customer base—remains unchanged. It’s a path forward that acknowledges both that the old way of doing things is still incredibly viable (no, the showroom isn’t dead), while also leaning into the possibilities that come with building consumer loyalty around the brand. “We are always guided by Sister’s philosophy, which still runs through every decision we make,” says Crater Harris. “She said, ‘Innovation is the ability to reach into the past and bring back what is good, what is beautiful, what is useful, what is lasting.’”

Homepage photo: Eliza Crater Harris, Susan Bartlett Crater and Apple Bartlett | Jonathan Becker