It’s obvious, but nonetheless worth saying: The interior design industry has been built on the talents of gay people. The inventor of the modern profession—Elsie de Wolfe—was a gay woman. Countless iconic decorators have been gay men. Design has long been both a safe haven and a showcase for LGBTQ creativity and enterprise. Anyone will tell you that this was, is, and will continue to be a good industry to be gay in.

That fact obscures a lot of nuance. Forty years ago, you might have seen a lot of gay men’s apartments in Architectural Digest, but you wouldn’t have read about their boyfriends or partners. And while the design world itself is a welcoming environment, gay designers who step outside the bubble of showrooms in cosmopolitan cities will recognize that intolerance is very much alive.

To celebrate Pride Month, Business of Home spoke with 10 gay men and women from all corners of the design industry to discuss their history, their experiences and their hopes for the future.

OPEN SECRETS

While the design world has always been a place of acceptance for gay people, it hasn’t always celebrated their sexuality alongside their talent. For much of the 20th century, even well into the 1990s, it was tacitly understood that many male decorators were gay, but that fact wasn’t always acknowledged in the media—or even, in some cases, by the clients who hired them.

Jamie Drake, designer: I didn’t have a coming-out-of-the-closet moment, particularly; I was in touch with the fact that I was gay since I was very very young. I knew some interior designers and assumed they were gay—there was only one I knew to be straight.

Robert Couturier, designer: Being raised in France, our attitude toward homosexuality is not the puritanical view that America has. It was just the way it was—there was no question about it. So coming to America was really strange. The refusal of acceptance was something I found really shocking.

Michael Boodro, former editor in chief of Elle Decor and current host of the Chairish podcast: It was the era of “confirmed bachelors.” It was very much an acknowledged but unspoken thing.

Raymond Schneider, publicist: I was hired right out of Nancy Corzine’s showroom to work for [designer] Harry Parkin Saunders, and he taught me everything I knew about business. Behind the scenes, everyone knew he liked men, but the way he carried himself would in no way, shape or form allude to his private life.

Couturier: [Several prominent gay designers] got married. And I’m not saying because they got married [to women] they didn’t have a couple’s life—I’m not passing any judgment on anyone. It just wasn’t acceptable to be gay, especially in society.

Drake: I think [gay designers who married women] probably felt they could socialize in circles with hetero couples easier being a couple with a traditional notion of a wife.

Couturier: I remember the president of Sotheby’s, Robert Woolley, he was absolutely wonderful. He was out—and I mean, he was completely out. He would go to dinner parties and people would ask him, ‘Who’s your wife?” He would point to his boyfriend and say, ‘This is my boyfriend and my husband and my wife. He’s everything.” It was something that very few people did. [Ed. note: Woolley’s partner died of AIDS in 1986, Woolley himself died of AIDS in 1996.]

HOW AIDS CHANGED EVERYTHING

The AIDS crisis devastated gay communities all over the world. The design industry was hit particularly hard, as the epidemic ravaged a generation of talent. One consequence of the pandemic was an upending of the established order: What before had been kept behind closed doors was now pushed out into the open.

Boodro: It was really the AIDS crisis that changed everything. Gay people no longer wanted to be secret. They confronted people: We’re here, we’re queer, get used to it. Because it was really a matter of life and death.

Couturier: You had people in the streets, which was different.

Boodro: People that ostensibly had not come out, or had not come out publicly—those people started dying. I remember Perry Ellis, and Rock Hudson obviously, but it had been happening a lot before that. When people started dying, it really ripped the pretense to shreds.

Drake: When I went to Parsons, I spent my first semester in a dorm. I was assigned two roommates and we became best friends. One was dead at 29 and the other one died six years later. I was the endgame caregiver to both of them, even though both of them had partners. Maybe it was easier if it’s not your life partner—to try and get through it. I know that was the case for one of them. It was just so wrenching for him—it was easier to turn over the intimate care and the making of promises that then were broken— that I did it. The promise was: Don’t make me die in the hospital. I ended up making the decision he had to go to the hospital. I broke my word, but it was the right decision to make.

I think the blessings and success I’ve had are for them as well. They might say, “Look at what you did, and look at your apartment, and look at this and look at that.” These are things that maybe they would have achieved, but they didn’t get the chance.

Boodro: After AIDS, people were no longer willing to hide or pretend. There was this whole controversy around outing people—it was a huge cultural shift. Suddenly, the pressure was to be out. I know it had a big effect on the design world.

Drake: It created a militancy.

Couturier: I was very close with [AIDS activist] Larry Kramer. I loved Larry Kramer. He was a wonderful person. Everybody always used to say, “But he’s in your face!” And I would reply, “He’s saying things to people that they need to hear. And he is right.” He was all for outing people. And I said, “Well, out people—it’s completely OK by me!”

There is a point where you don’t have to be genteel and polite. Because the more genteel and polite you are, the more people take advantage of you.

PUBLISHING OPENS UP

The world of interior design media reflected the design industry at large: Gay men and women were generally free to be themselves within the industry, and the rooms they published were frequently designed (and lived in) by gay people as well. But it wasn’t until the 1990s that what had once been subtext became text.

Boodro: Say a shelter magazine featured a designer’s home, and it was a gay designer, which many of them were. They would never really show the boyfriend or the partner.

Sabine Rothman, former editorial market director at Hearst Design Group: I went in very transparently. I’m pretty transparent in general, and that was not going to be something I was going to hide. It was an incredibly inclusive environment [at Condé Nast, where Rothman’s career began]. I had a lot of mentors and colleagues who openly accepted [my wife] Amy. We were out at parties and events all the time; it just felt very natural and supported.

Boodro: I always felt like [founder and former editor in chief of House Beautiful] Marian McEvoy and [former editor in chief of Elle Decor and Architectural Digest] Margaret Russell didn’t get enough attention for the way they were willing to present gay couples. When I worked with Margaret at Elle Decor in the early ’90s, she would get a few hateful letters every time she published a house of an acknowledged gay couple. And that wasn’t that long ago.

Rothman: In terms of how people name their partners, that has changed, and the way it was covered changed as a result. A lot of that was the result of [the legalization of gay marriage in 2015]. If the term “husband or wife” isn’t available, you don’t use it. … Whereas once there would have been a discussion about how to cover a same-sex couple in a shelter magazine, now you just do it.

Boodro: Were there instances of people who should have gotten promotions or jobs that they didn’t get, and maybe their being gay was a factor? Yes, there were. But it certainly was more open than a lot of fields. And there’s been an appreciation for the talents of gay people in these industries for a long time, whether it was acknowledged that they were gay or not.

GAY WOMEN IN DESIGN

Interior design in its modern conception was invented by a gay woman: Elsie de Wolfe. Strange, then, that over time the profession came to be associated with gay men. There are, however, many gay women in design, and their visibility in the industry may be on the rise.

Boodro: In the magazine business, there was a lot more openness about gay men than there was about gay women, and that’s probably still somewhat the case.

Darla Powell, designer: There are some gay women locally here in Miami who are decorators and who have reached out to me. I had another one reach out with some fan mail—she is in Florida as well, she’s also gay and getting into interior design. I have a feeling there’s probably more than the stereotype would have you believe.

Rothman: I don’t know necessarily why gay men have been more visible in the industry than gay women. But I suspect that it has something to do with people’s perceptions about who has taste.

THE CLIENT QUESTION

Within the industry, tolerance is the norm. But much of a designer’s career is spent interacting with clients, who bring varying levels of understanding of and comfort and experience with the gay community to the table.

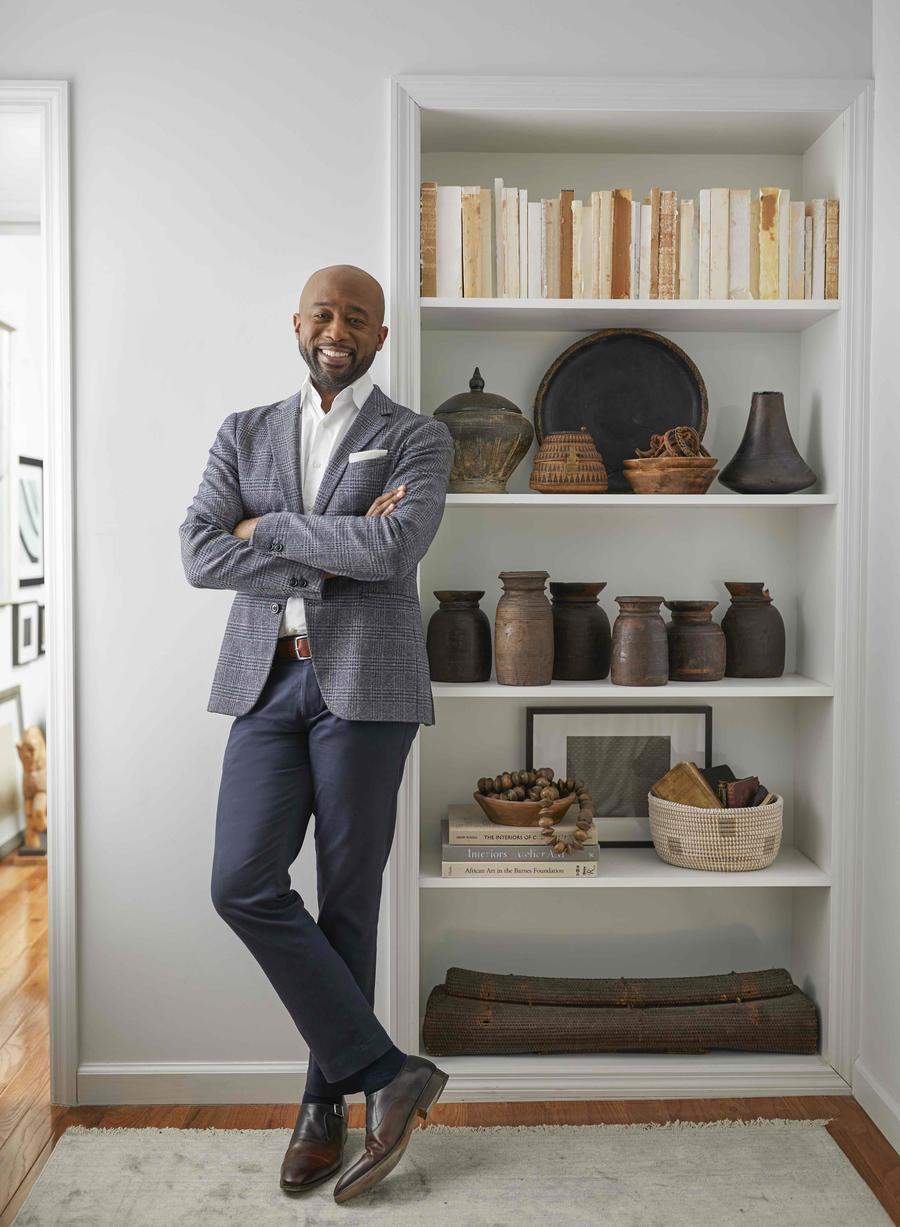

Corey Damen Jenkins, designer: In the industry, it’s not so much a big deal to be gay, but when you’re working in the field, it can be.

Drake: I can only remember one client who felt uncomfortable. My manifestation was gay—I had very long hair. Ironically, he was in the hair replacement business. I think there was a discomfort there that I was gay, and the project did not go forward.

Jenkins: I had one client who thought for years I was straight. She had affiliated gay men with being very effeminate, with a limp wrist and a high-pitched, lisped voice—a stereotype. We were having dinner with her husband, going over the project. I’m not exactly sure how I shared with them that I was gay, but somehow it came out. And they were shocked!

They were deeply religious people, and they were raised not to agree with [being gay] from a scriptural standpoint. When I shared with them that I, too, was raised in a very strictly religious household, and that my family refused to accept me for being gay—to this day—it broke their hearts. She said, “But you’re so nice, you’re such a good person, you’re always giving back to charity, you’re so giving of your time with me and my kids and my family. And yet your family doesn’t associate with you?” And I said, “No, because of something I cannot change.”

It kind of shocked her, because we had fallen in love as friends, and as co-workers on this project. By associating with me closely, getting to know me, laughing, literally crying, you know—the ups and downs of building a large home—it helped her to get to know a gay man without really realizing that she was doing it. It dispelled so many of the misconceptions and prejudices she had held for a very long time.

Eche Martinez, designer: After the Pulse shooting in Orlando, I was really distraught. I happened to have a very quick meeting with a client I’d been working with for years the Monday after it happened. I was so upset, and I said, “I’m sorry I’m not as effervescent as I usually am, but this really hit close to home.” She connected not only with the severity of it, but she said, “I never told you, but when I was growing up, I lived in Orlando; two of my best friends were gay and we used to go to gay clubs.” She had been thinking about the same thing over the weekend. I wasn’t expecting to hear that, and we really connected. It’s not like, I’m in the gay bubble, these people are in the straight bubble.

Powell: In the beginning when I was doing social media, I was like, How transparent do I want to be? Do I show pictures of me and [my wife] Natalie on my feed? And once I decided, “Screw that, I am who I am, and if they don’t like it, they can go pound sand,” the clients really started pouring in. I did lose a few followers on Instagram at first, but it skyrocketed when I really started honing in. Now our clients are ideal clients and nobody ever has a problem with it. They know it’s coming!

OUTSIDE THE BUBBLE

It may be rare to encounter intolerance about one’s sexuality in a fabric showroom. But when designers leave the comfort of a famously open-minded industry, things can be different—especially when projects take them outside of coastal enclaves and liberal-leaning cities.

Drake: The last time I experienced [homophobia] was my first time in Denver, walking down the street in some giant fur coat—and they weren’t coming after me because of PETA. But that was a long time ago.

Powell: In Miami, overall I feel pretty comfortable. When I go up to northern Florida, forget it. People are driving around with rebel flags on their pickup trucks, and I’m like, You know what? Maybe my wife and I are just “friends” here.

Mikel Welch, designer: I went to college in the south, in Atlanta. There’s a joke that if you go outside of the 20-minute circle, you’re in Georgia; the rest is Atlanta. When I step outside that bubble and go into a Hancock Fabrics or something like that—yes, in smaller towns, it is not as accepting. You’re going to have a harder time

Not that I would walk in there raising a flag. But my jokey manner that I have, I may not have that going in there. I might tone down myself to make it more palatable to them—not that I should. It’s a toning down and being aware of where I’m at and how it’ll be a bit easier.

Rothman: I’ve been pretty lucky. I’ve been on photo shoots where I really disagree with the homeowner on their politics, but it doesn't necessarily move on to the subject of their thoughts on [gay rights]. I’ve never felt uncomfortable. I have been shocked by some people’s politics on economic policy, but I probably shouldn’t have been.

Rio Hamilton, designer and marketing expert: [In Las Cruces, New Mexico, where Hamilton has a home], it takes so much explaining! I tell people that I’m an interior designer, and I do branding and marketing for other people who are part of that business. Most people say, “Oh, you go to Ashley Furniture and buy stuff for people?” And I say, “Yes, but I would never go to Ashley Furniture.”

Couturier: One day, I was flying down to Atlanta; it was 7 o’clock in the morning, I was half awake, and this very proper American lady sat next to me and wanted to talk. She was asking questions, which became more and more pointed: What’s your religious background? Where do you come from? I realized I had become the picture of evil, as far as she was concerned. A foreigner, gay—and when she asked me what religion I was and I said, “Actually, I’m Jewish,” she looked at me in complete horror.

Welch: I stage for a closet company, so I’m typically gone at least 10 days out of each month to set up a showroom. I’m in Phoenix, Arizona, or Mobile, Alabama, and every time it’s different. I do have to tailor my approach—in a lot of these red states, they don’t understand why a man is in this position. “This is a woman’s job” is kind of the undertone that you get.

ADDING RACE TO THE EQUATION

A national conversation about race and inequality has rippled through all corners of American society in the wake of the killing of George Floyd, and the design world is no exception. Perhaps for the first time ever, the industry is taking a hard look at something designers of color have long known: gay or straight, racial inequality is still very much alive.

Jenkins: Being Black and gay is a completely different path than being white and gay.

Welch: I’m very proud of the design industry, and I’ve been happy to see that the design community is listening as a whole on the issue of race. But one thing I’d like to see is an exploration about diversity within the LGBTQ community. When I walk through the showrooms, there aren’t many Black members of our community that are prominent. I do see lots of white gay men, but I really don’t see much other than that. I would love for us, as we become more inclusive, to take a look at that. And not not just from a sales role, but in a leadership capacity.

Jenkins: There are all the stereotypes about how gay men are supposed to talk and act. Well, if you want to turn that switch off and act very conservative and have a deep voice and talk about sports, a white gay male can do that. A Black gay male does not have that option. You can be as unstereotypical as you can possibly be, but you will always be Black.

Welch: Racial relations within the gay community are just as bad [as the outside world]. You would think it would be a situation where you have two minority groups, they would feel some sense of camaraderie, but it’s not the case. And it’s sad. Once on a dating app, I had someone send me a message that said, “No coons.” There are some bars in Chicago and Atlanta that will say, “No baseball caps, no hoodies and no hip-hop music.” It’s saying it without saying it. Even with work—if there are four Black people together, it’s a “Black business.” But if it’s four white people, it’s just a business.

Martinez: More and more, we’re starting to realize that even within a very open-minded society like San Francisco, there should be more inclusion. The Black community keeps getting decimated in the Bay Area, especially the queer Black community. There’s definitely lots of room for improvement.

Welch: I have a difficult time doing gay pride interviews. I want my pride to be out there, but because I get doubly discriminated against, I oftentimes don’t get excited about it. There are still issues that need to be corrected.

I am a gay man and I’m proud of that. The design industry has been very kind to me. I’ve been able to make some tremendous strides, but I’m kind of at a point now in my career where I’ve got to speak out because it’s not just about me. I’ve got to make it easier for the people coming behind me now.

SAFE HAVEN

The design industry has always been a welcoming place for gay men and women—a place where many find a community that eluded them in other fields.

Boodro: [My being out] was understood but not discussed when I started in publishing. I’m sure I thought I was hiding it more than I ever did. But the nice thing about the design world is that within that small world, you didn’t have to pretend. It’s not like I worked for a private company or even the government, where being gay could cost you your job.

Jenkins: It was pretty much don’t ask, don’t tell [at the car company where I worked prior to starting my design firm]. This was back in the late 1990s. I was kind of head down, blinders on. I wanted to do my job and go home. [When I started as a residential designer], being gay was much more out in the open.

Martinez: Growing up in Argentina, there was this overlap between your family and your friends from high school. It was never like, OK, five guys are gonna go to a gay bar. When I left Argentina 10 years ago, there was no “the gay district” or “the gay bar.” Moving to California, I really made a core group of friends who were gay men for the first time in my life.

Hamilton: In [UC Berkeley’s interior design program], it was a relief: It was OK to be openly gay. Out of the classmates I had, maybe 50 percent of them were gay, and we all shared a common interest—not only in men, but in design. My first gay friends were in design school.

Powell: I’m really a newbie, but my experience has been so positive. I feel so welcomed and accepted into the design industry.

Schneider: We’re in a community that fully encourages us and celebrates us. The last decade, to me, has been the most accepting of all.

WHAT’S CHANGED

In some ways, the raw facts haven’t much changed in 40 years. The design industry was, and is, a place where gay talent is celebrated. What has changed is the explicit celebration of gay identity, and the degree of normalcy.

Boodro: I used to think that you couldn’t be a decorator unless you lived on the Upper East Side, had a navy blazer with buttons, and wore a tie all the time. It was a different world.

Schneider: I keep on going back to charities like DIFFA and Alpha Workshops that organized an entire industry. It was always welcoming to gay people, but we weren't running around with rainbow flags. It's really acknowledged now—it's discussed, and it’s reflected in social media more than it ever was.

Martinez: My experience of being queer back home was just a bunch of guys going out for dinner who happened to sleep with men. I slowly started to read more about it and get the subtleties about what it really means to be queer, or gender nonconforming or nonbinary. There’s definitely a more involved conversation.

Couturier: Young people today are probably equally as fluid as we all were when we were 16 or 17, except now it’s completely understood and completely normal and no one asks a question. Everybody understands.

Boodro: Young people are just much more open and relaxed about it. Even when you go outside the design world—to all my nieces and nephews, it’s just a given. It’s not an issue. To us it was such an issue, and we fought so hard that sometimes you can’t quite believe you’ve won the battle, and you still want to fight the battle. Sometimes you think, Oh, these kids don’t know what we went through, they take it for granted! But that’s the way it should be.

Homepage photo: Shutterstock