About two weeks ago, a funny thing happened on the internet: Laurel & Wolf came back online.

The promising e-design company, founded in 2014, netted a partnership with Home Depot and more than $20 million in VC funding before spiraling out of control (and then out of business) in early 2019.

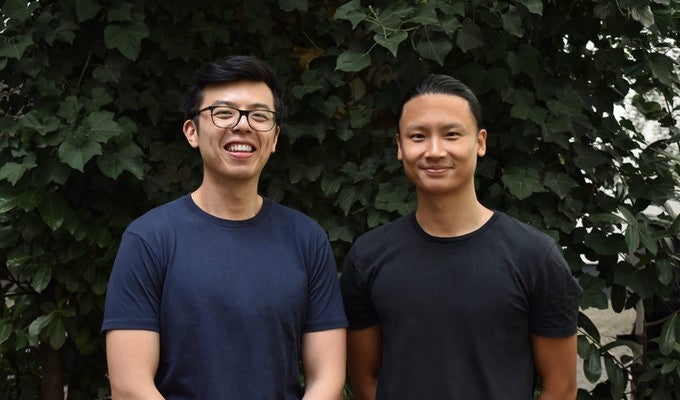

The duo responsible for the brand’s revival? A pair of young Canadian internet entrepreneurs living in Berlin who bought the domain at auction for a little more than $3,500. They hired a few Pratt- and Parsons-educated designers they met through LinkedIn connections to do the design work and relaunched the business—all in less than two weeks.

“I was just browsing domain auctions one day, because I’m in SEO, so I grow traffic on Google, and that’s one of the tactics: You buy up expired domains,” explains Jacky Chou, an engineer by training who turned to internet marketing after graduation. “Laurel & Wolf goes on sale and I didn’t think anything of it—I just checked the SEO metrics and decided to pick it up at a premium. And then we found out the history of the brand.”

The brand was actually relatively expensive for its suboptimal SEO ranking, Chou says—in fact, the site wasn’t ranking at all when he bought it. Instead, search results were filled with biting Glassdoor reviews, articles on founder Leura Fine’s mercurial tenure running the company, and competitors’ AdWords results.

Instead of being deterred, Chou and his business partner Albert Liu, who specializes in Facebook marketing, dug into the stories of the company’s demise. “Reading more about the tragic downturn, we saw an opportunity to take over a preexisting brand,” says Chou. “I feel like we can make it better—learn from their mistakes, provide value to customers where the old management and competitors in the industry fell short—and that’s what we’re currently doing. Right now the revenue trajectory is really strong.”

The company also now ranks at the bottom of the first page—or, at worst, top of the second—in searches for online interior design.

Chou had other plans for the site when he picked up the domain name. “I just liked the name because it’s brandable,” he says. “I was actually going to make it into an affiliate site—a product review site like The Spruce. But I decided: Why don’t we try everything at once? We started by selling some furniture that we had in stock in the U.S., but then rebranded again and decided to focus on interior design.”

Laurel & Wolf was one of the earliest sites to popularize the concept of e-design. Launched in 2014 by Fine and entrepreneur Brandon Kleinman, the platform quickly gained popularity and secured over $20 million in venture capital investment. However, as Laurel & Wolf grew, it struggled with a variety of problems, ranging from the skyrocketing cost of customer acquisition to an abrasive company culture. Critically, the startup never achieved profitability at scale, and wasn’t able to secure another round of funding. Over 2018, Fine fired most of her staff and moved the company from its plush West Hollywood office into a WeWork before eventually disbanding. Early in 2019, the site’s assets went up for sale through a third-party broker. (Chou and Liu haven’t purchased the back-end software that powered Laurel & Wolf, but hope to acquire its social media handles.)

Laurel & Wolf won’t be Chou and Liu’s first venture together. In 2018, the duo—high school classmates in Vancouver who both moved to Berlin to work in marketing, Liu as a Facebook consultant and Chou as founder of the SEO agency Indexsy—launched a dropship retail operation that Chou calls a “‘practice what you preach’ case study” in a thread on Reddit. The business model was essentially to build an online brand around an assembled assortment of goods, then use SEO and targeted social media marketing to fuel demand; customer orders were then fulfilled directly by the factory that designed and manufactured the product. Within eight months, they reported that they were spending nearly $70,000 a month on Facebook and Instagram ads. Their company was also netting upwards of $250,000 in sales per month; they sold the company in January for an undisclosed amount. The pair also sell home furnishings on Amazon and launched the dinnerware company Far & Away six months ago.

They plan to take that same advertising approach to drive growth for Laurel & Wolf, rolling out ads across Facebook, Instagram and Pinterest starting in May. “There’s a demand cap [on growth from search], which is the number of people who are searching for interior design,” says Chou. “To grow this market, you have to educate people about online interior design, so with that we’ll have to start running advertising and prospecting campaigns.”

Initially, that may mean sinking more capital into the brand before seeing a return. “Losing money initially on Facebook is almost unavoidable, but you have to dive into the data to learn from it,” Liu wrote on Reddit. “Whether it’s one segment of the audience performing better or one [piece of] creative doing better, you have to continuously tweak your targeting/creatives/product offering based on the results.”

The combination of e-commerce sales and online design services is not a new approach to the e-design business model. Most companies selling online services have quickly found that the artificially low cost of design services to get customers in the door won’t be what turns a profit—it’s the margins on furniture sales. While competitors like Havenly and Modsy have both explored a mix of retail products and proprietary furnishings, they normally seek to integrate the two halves of the business seamlessly. Even the original Lauren & Wolf platform eventually expanded its focus to include wholesale furniture, though the shift came too late to reverse the company’s misfortunes.

Laurel & Wolf’s new owners are taking more of a grab-bag approach. Their “follow what resonates” mentality in Facebook advertising applies in some ways to the business as well. The site currently includes several articles that recommend products, and Chou believes affiliate content will be part of the company’s long-term revenue stream, in addition to selling product and growing the company’s interior design services.

The site, which has been rebranded in a wash of pastels, currently offers three packages: two designs for one room, for $75; two designs plus two revisions for up to two rooms, for $220; and two designs plus five revisions for up to four rooms, for $450. Chou says the lower- and middle-tier options are most popular.

So far, the work has been powered by a team of six: Chou, Liu, a customer service representative, and three Pratt- and Parsons-educated designers Chou was connected to by friends after posting to LinkedIn that he was hiring design talent. “They went to these ridiculous schools, are [working] at big firms, and now they have some extra time because of COVID-19,” he says. “The interior designers we are working with right now are rock stars. I’m seeing their designs and I’m like, ‘Holy cow!’ I could never have imagined the designs people are getting for this price.”

To compete with big e-design companies like Havenly and Modsy (whose entry price points are $79 and $89, respectively), it was essential to keep package costs low. For now, Chou says they’ve attracted design talent by pointing to the company’s potential for growth. “We were like, ‘We see the value in your service and your designs, but we’re going to be completely transparent that we can’t pay you a rock star salary,’” says Chou. “We’re going with a commission revenue-share basis, so we pass on a very large portion of our profits and say, ‘This is what we’ve done in the past, we would love to have you on board and grow together,’ and sell them our experience and company vision—in, like, two weeks.”

For now, Chou and Liu are exploring venture capital to stem a problem other e-design sites are all too familiar with: online design’s cash flow problem. “Typically when you sell online, you get that cash in seven days,” explains Chou, who is in talks with VC firms that tried to court the duo in their previous businesses. “[But with an e-design model], when you want to grow—let’s say we want to put $100,000 into paid advertising and grow that into $300,000—that $300,000 will come in a month later because people are still deciding if they [want to buy the] furniture or not. So then you have negative $100,000 in limbo, essentially. That’s why we would need the capital.”

Homepage photo: Jacky Chou and Albert Liu | Courtesy of Jacky Chou