A week ago, I placed an ottoman onto the floor of a showroom and quickly upholstered it in a patterned fabric. But the ottoman, technically speaking, did not exist. Let me rewind.

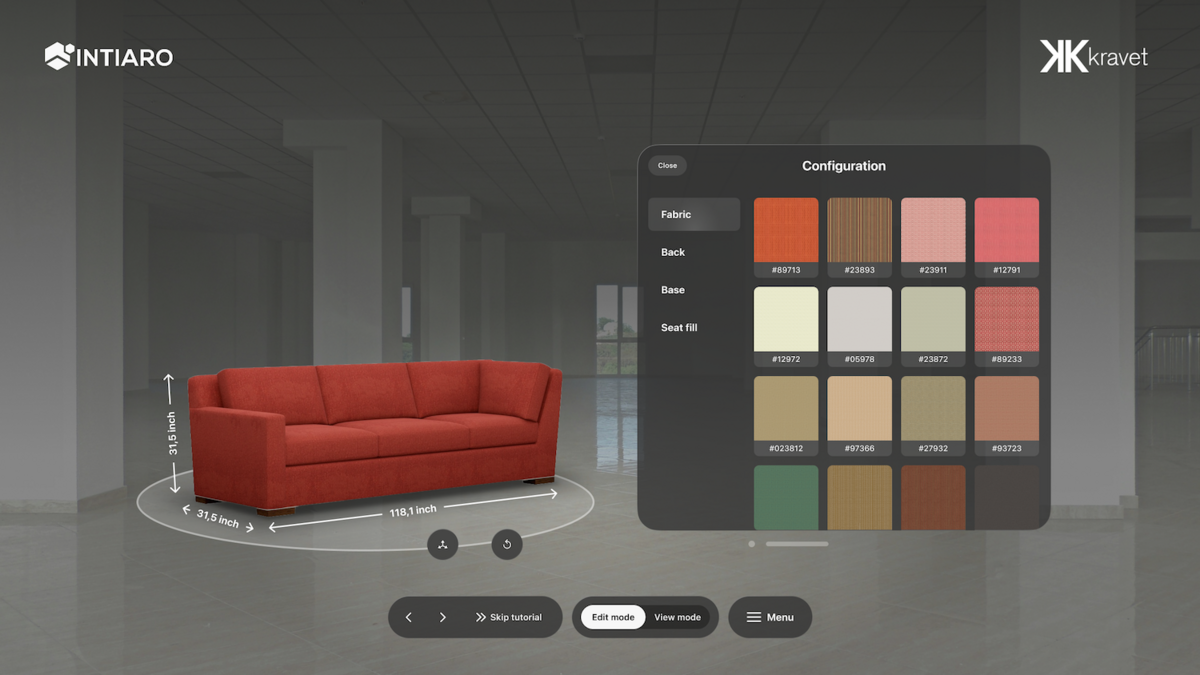

The showroom—which very much does exist—belongs to Kravet. I was there at the fabric giant’s High Point outpost during Fall Market, partially to check out its latest collaboration with fashion designer Joseph Altuzarra, but also to road-test a new piece of technology called Arrange 3D. The tool, built in collaboration with 3D visualization company Intiaro, is an application for Apple’s mixed reality headset, the Apple Vision Pro. It allows users to don the device (which looks like a pair of high-tech ski goggles) and place virtual furniture in their real environment, then clad it in Kravet fabric and inspect it from 360 degrees.

A press release announcing Arrange 3D described it as “light years” beyond the capabilities of preceding augmented reality technology, and the “closest thing to putting [a] piece on the floor in real life.” In other words, on that cloudy North Carolina afternoon, expectations were high.

The Apple Vision Pro involves a quick setup, pairing the device with user’s eye movements, hand and finger motions (unlike similar devices, there is no controller). This process was hampered a bit by the fact that the headset doesn’t fit around glasses, and without them, my vision is terrible. But with a little help from a showroom employee, I was able to get the headset working. Now it was time to decorate.

Arrange 3D’s interface is no more complicated than a tool you might use to insert furniture into a room in The Sims. Scrolling through a list of blank forms—everything from sectionals to beds to stools—you pick an item, “drop” it into the room, then select a fabric to “upholster” the piece. I made the mistake of selecting a bed at first, and it quickly filled the room. I deleted it, then selected a relatively simple ottoman shape, and a patterned fabric to match. Within seconds, there it was on the floor in front of me.

It is difficult to describe the weirdness of knowing that there was no ottoman on the floor but nonetheless seeing one in shockingly vivid detail. Even stranger, as I shifted from left to right, the virtual ottoman perfectly maintained its place in the room—the way a real ottoman would. Even on my hands and knees, inspecting it from inches away, it looked like a genuine ottoman in Kravet fabric. (I resisted the urge to give it a sit test.)

As I peeled off the headset—reassuringly, the ottoman disappeared—I had to admit that, true to the hype, this was indeed fairly close to “putting that piece on the floor in real life.” What could that kind of technology mean for designers?

EARLY OBSTACLES

It’s worth noting: We’ve been here before. AR and its close cousin virtual reality have existed in some form since the 1960s, when scientists built bulky contraptions that could, in primitive form, superimpose computer-generated images onto a stereoscopic display. As long as the technology has existed, there has been speculation that it could be put to use in the worlds of architecture and interior design.

In the 21st century, as the visualization technology itself has improved, that speculation has only gotten stronger. The introduction of smartphones and high-speed internet meant that it was possible to send fairly sophisticated 3D models to a device in someone’s pocket thousands of miles away. A quick scroll through Business of Home’s news archive shows that Arrange 3D is hardly the first AR application aimed at the home industry—as early as 2016, Microsoft was pitching its own AR goggle device, the HoloLens, as an aid to designers and architects. Since then, retail brands ranging from Ikea to Ethan Allen have rolled out AR tools to help consumers visualize their products at home, mostly through a smartphone or tablet camera.

The promise of AR in the home industry is not hard to understand. Unlike crypto or AI, the technology seems like the solution to an actual problem commonly described by designers and retailers alike: Clients just can’t see it. Unlike a new pair of jeans, you can’t really “try on” a pair of curtains at the store, or see precisely what a new sofa will look like in the corner of your living room. Augmented reality seems to offer a fix for that.

Despite all those factors, AR has thus far failed to become an industry game changer. Brands are certainly offering it—you can still use Ikea’s app to place a blocky representation of a Billy bookcase in your room—and companies that create the underlying technology tease statistics about how much more likely AR-using customers are to make an eventual purchase. But it is still a niche technology, and certainly not part of the toolkit of the average designer.

According to Intiaro co-founder Michal Stachowski, the first wave of furniture AR applications had many problems. The graphics looked like cartoons. Early headsets were too expensive, and they would give users motion sickness. Using a tablet or smartphone to deliver the experience solved that problem, but created another one: The “window” of a small screen can’t capture what a piece of furniture will look like in a room. “The problem is simply the scale of the items,” he explains. “When you place a big sofa in a room, you’d have to walk backwards a lot to see it, and if the space itself isn’t that big, you end up only being able to see a little sliver of it through your screen.”

MAJOR UPGRADES

This time may be different. As Meta rapidly developed its own Quest line of headsets over the past five years, Apple followed suit—a sprint that culminated in this year’s release of the Vision Pro. Both product lines solve the first-wave AR problems: The graphics are far more vivid, and the form factor (a headset, as opposed to a smartphone) allows users to see what a piece of furniture might look like in a more immersive fashion.

Kravet had already been working with Intiaro on a web-based configuration tool that allowed customers to quickly render a 3D model of upholstered furniture when the Apple Vision Pro debuted in February. The new device’s technical prowess convinced the brand to sign on to develop an app. “For a couple of years I’ve been approached by different companies doing VR work, and we always batted it away because of the issues with VR in general—the motion sickness, and also the fact that what you would get is fairly cartoony,” says Jesse Lazarus, Kravet’s chief technology officer. “When we bought an [Apple Vision Pro] and brought it into the office, we were all blown away by how the mixed reality environment worked, and the ease of use.”

Another factor in this new wave of AR enthusiasm is simple economics: Headsets are getting more affordable on both sides of the equation. While the Apple Vision Pro carries a hefty $3,500 price tag, the cheapest version of Meta’s headset is $299 at retail. Tech companies will continue to develop boundary-pushing devices (Meta has a not-yet-for-sale prototype AR device, Orion, that reportedly cost the company $10,000 to make), but the general consensus is that a pretty-darn-good AR headset is only going to get cheaper for the average consumer.

On the development side, the cost savings are real too. In earlier versions of this technology, developers like Intiaro would have to code much of the underlying software from scratch. Over time, both Apple and Meta have built developer toolkits that take care of much of the grunt work involved in creating an AR-based app. After inking a deal with Kravet, Intiaro was able to create a working version of Arrange 3D in roughly four months. The challenges had far less to do with making mixed reality work, and more to do with importing the collection of a fabric brand with thousands of SKUs.

“Working with [another vendor], the amount of possible configurations they had for their furniture was 10 to the 52nd power. Which is just a crazy amount of choice, so we had to develop an approach that solves that,” says Stachowski. “With Kravet, the challenge is simply getting as much fabric as possible into the system—we’re coming up on 3,000 SKUs, but that’s tiny compared to the overall collection. … Then of course the challenge is coming up with a user interface that makes it easy to navigate through them.”

Though Kravet is the first major trade brand to adopt this particular kind of technology, the speed at which Intiaro was able to roll it out suggests that others could soon follow. It may not be long before home brands of all stripes are able to offer AR compatibility along with a standard tear sheet.

DESIGNER IMPACT

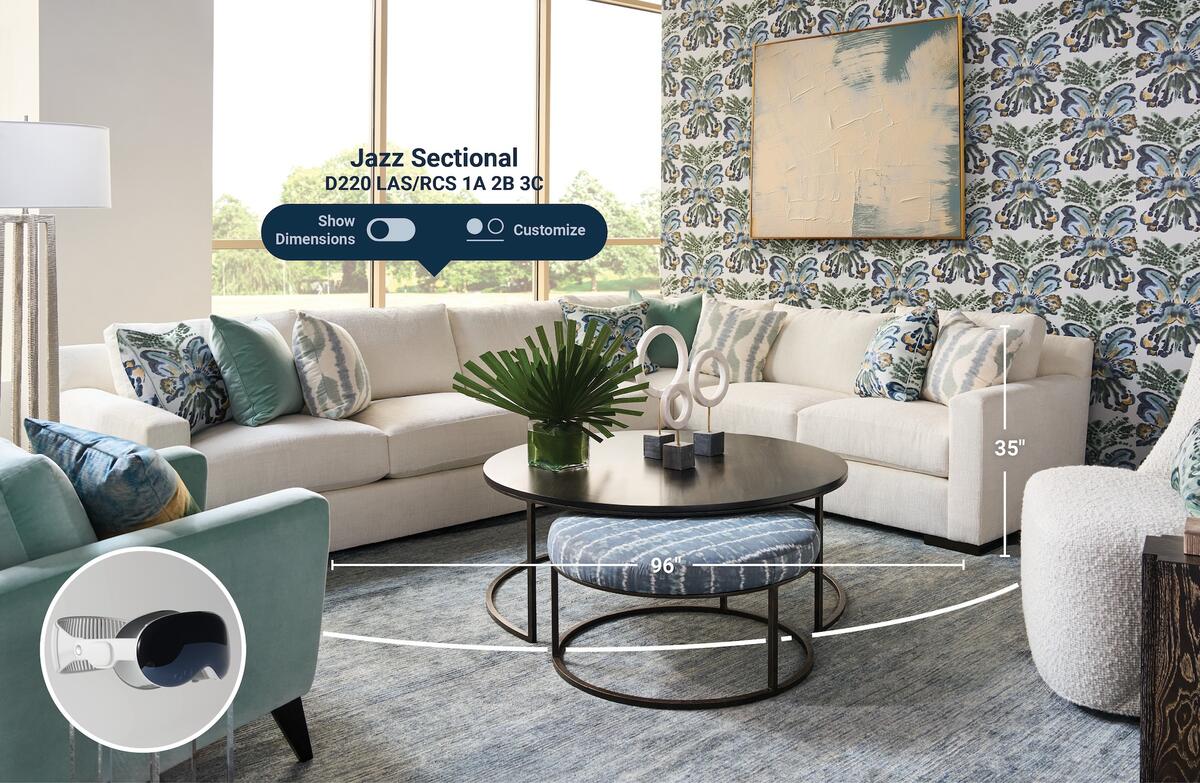

Though Lazarus is enthusiastic about the long-term opportunities Arrange 3D might unlock for Kravet, he was careful to stay realistic about the short-term. The app will be rolling out on Apple’s Vision Pro public store in the months ahead—available to all who own the device—but for now, the team expects that it will mostly be used in Kravet showrooms as a sales tool, not necessarily by designers presenting items to clients in their homes.

“We have 2,500 frames in our line. We can only show a handful of them in showrooms,” says Lazarus. “So the hope is that the device becomes a way for us to do a more engaging ‘endless aisle’ concept, to be able to show the breadth of product.”

The showroom rollout itself will be relatively modest, with a handful of locations adopting the technology at first. Part of that, says Lazarus, is not wanting to saddle showroom employees with “just another thing” to learn and implement into the customer service experience. But another real challenge is fundamental to AR: Even though the furniture is virtual, you need actual empty space to place it in. Most fabric showrooms are fairly crammed with product—hard to justify carving out 100 square feet of emptiness for the sake of digital furniture.

Kravet’s bet on AR is a toe dipped in the future, not a massive investment that radically transforms the brand’s approach. And it’s worth noting that, while the hype around AR/VR goggles is based on real advancements, the public has not embraced the technology as warmly as tech companies have hoped. Analysts say Apple’s Vision Pro has thus far underperformed the company’s sales expectations and is struggling to attract developers to create apps for its ecosystem. Meta’s far cheaper Quest 2 headset has reportedly sold 20 million units—healthy sales, but not a ubiquitous consumer product.

Despite all these very real hiccups, it’s worth at least thinking about a world in which more clients have AR goggles and it’s easier and easier to showcase design concepts in immersive 3D. If the technology does come to be adopted more widely, it will likely have real effects on the way designers work.

The obvious boon would be the ability to show clients exactly what’s inside your head. Over the past decade, digital renderings have gone from an expensive rarity for designers to a relatively affordable, must-have tool for many firms looking to sell their vision. Mixed reality presentations would essentially allow users to be inside a rendering—the technology would likely resolve a lot of designer-client misunderstandings.

There are potential downsides too. One is the risk of disruption: AI-generated renderings are already pretty good. Imagine that technology, supercharged with the immersion of augmented reality. Surely at least some customers would rely on an algorithm to design their home if they could “see” the result right before their eyes.

Another challenge will likely be a version of the same issue designers have with renderings already: They can make things awkward. When a client falls in love with a digital image, they often expect the final result to look exactly the same—which leads to disappointment if, say, the sofa turns out to be a shade lighter than the rendering. Having a precise digital image to work toward can also rob the design process of creative spontaneity. If your goal is to make the final product look like a rendering you cooked up eight months ago, there’s less of a chance that you’ll stumble upon the unexpected last-minute decision that makes the project truly come alive.

For precisely those reasons, some designers who once swore by renderings have abandoned them. One—at High Point Market, the same day I saw the Kravet demo—told me that they’ll only use hand-drawn illustrations now. “It gets the client’s imagination going,” she said. “We tell people we’ll have a ton of fun along the way, and that it’s going to look pretty at the end, and that’s what matters most.”

But for those who love new technology—or whose clients lack visual imagination—advances in augmented reality will be a welcome development. However long it takes, in whatever form, Kravet will be ready. “[Our thinking was] Let’s make sure that we’ve got the content necessary to power these types of experiences, so that once it becomes more accessible, we’re already there,” says Lazarus. “Let’s get in early.”