All the Pinterest boards in the world can’t compete with a good design book. For most designers, debuting one is a major professional milestone—the trade equivalent of putting out a solo album. Like most artistic pursuits, these beautiful works conceal some fascinating behind-the-scenes mechanics. In a new series, Open Book, we invite two designers with recently released books to share the ins and outs of the process—from landing the contract and shaping the content to reflecting on the glossy final product.

Justina Blakeney and Max Humphrey are both unstoppable designers who crafted their new books to reflect exactly who they are as creatives. And that’s part of the appeal: Both can be credited with ushering an era of optimism, authenticity and self-reliance in a design scene that had long craved relatable protagonists. They’ve each made their mark as independent thinkers with the stylistic chops to not only design spaces, but also do production and art direction and build active communities.

Neither is formally trained in interiors or architecture—Blakeney has a background in graphic design, while Humphrey was a musician in a punk band. Both have spent countless hours perusing dusty vintage shops and relied on gut instinct with the deeply held belief that creating a cool, personalized space is possible regardless of background or budget. Online and over social media, that message has resonated. Beyond the brand collaborations and licensed product collections, it’s the spirit of what they’ve each built—an egalitarian, you-can-do-this uplift—that makes their approach so modern.

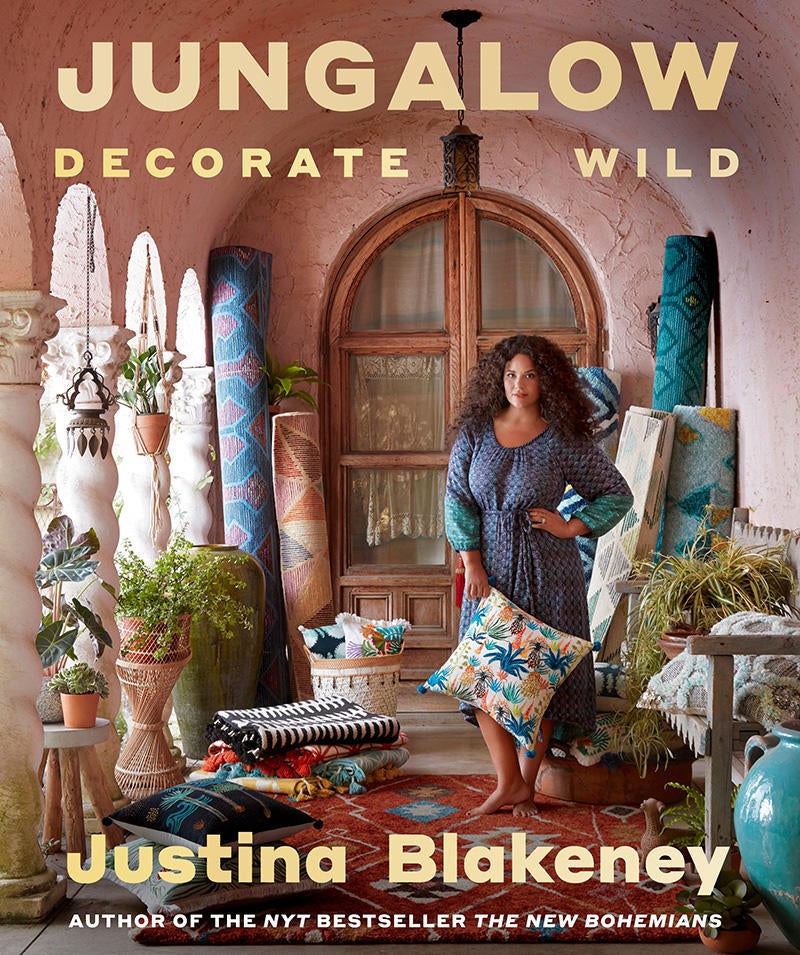

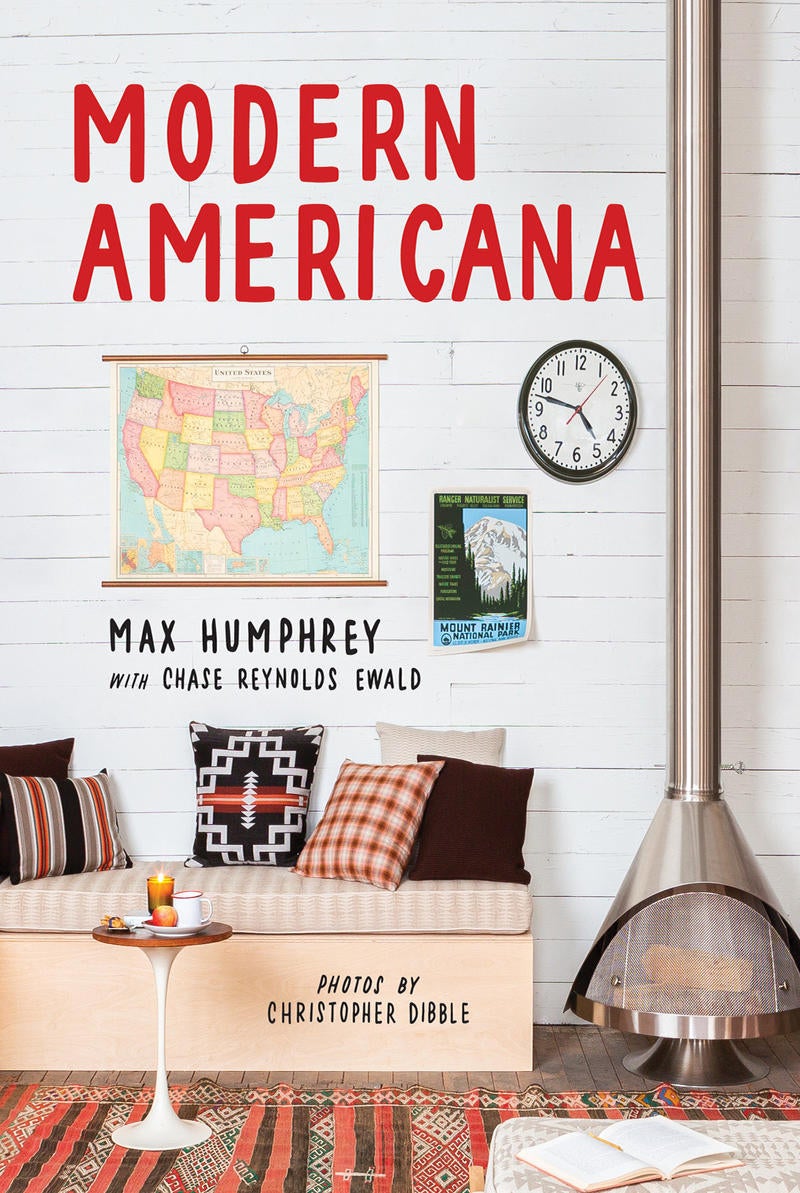

Blakeney’s work occupies a vibrant and luscious realm known as the Jungalow in Los Angeles, which started with a namesake blog in 2010. Decorate Wild is her third design title. Humphrey, meanwhile, is based in Portland, Oregon, where he practices a layered, comfortable style called Modern Americana. His debut title of the same name is a visually driven tome that emphasizes heritage, nostalgia and the pure pleasure of collecting. Here, the two friends discuss the slog of editing, what DIY actually means and what it’s like to be uncompromising in your voice.

Justina, Decorate Wild is your third book. What motivated you to create this one?

Blakeney: I love making books. I love everything about it. I love concepting books. I always have book ideas. I have several right now. I love creating outlines and figuring out how to fill in the chapters, trying to understand what’s going to move and inspire people. And also trying to understand what I can provide in print that I can’t provide in a digital medium. I just love them.

There are definitely points in this last book where I was like, ‘Why did I do another book?’ Because it does take forever. And it’s hard. I don’t consider myself a traditional interior designer—I’m a creative. I luxuriate in the process of writing, photographing, styling, doing the composition, figuring out which type is going to be bold, what things we want to say loudly and what things are going to be quiet, and how much of it’s going to be personal. How much of it’s going to be didactic? How much is based in history or the future, or how much of it’s going to be a DIY? How much do I want it to just be eye candy? I like thinking about all these things with each one of my books. It’s just an obsession of mine.

That is a perfect contrast, because Max, Modern Americana is your debut book.

Humphrey: Yes. Justina, I listened to your podcast with [The Business of Home Podcast host] Dennis Scully the other day, and you mention how much you love making 30-page PDFs as the outline of your book. I’m the opposite. I mean, I didn’t know how to make a book, but I definitely couldn’t do an outline. I didn’t really know where it was going; I had some flexibility where I had an understanding editor and a co-author, [lifestyle writer] Chase Reynolds Ewald, who’s written books before, to sort of guide [the process]. But I’m so visual that I didn’t know what this book was going to be until I got the first round of stuff back from the book artist.

Justina, are people surprised when you tell them how much you like outlining books? And do you like it, or is that just your process? It’s painful to me.

Blakeney: Both. I’m very concept-driven in everything I do. So, I like to flesh out concepts before diving in and coloring in the lines. But I have a graphic design background. So for me, laying out the books and doing all that—I actually don’t know how to make a book without doing that. Because I need to see the flow. I need to see what goes on one side of the page, what’s going to go on the other, which photos I want to be small, which ones I want to see as a double page spread. I want to know all that because I’m a control freak.

Humphrey: Were you doing basic layouts?

Blakeney: I lay out every book in InDesign and hand it to them exactly how I envision it, so that it’s close to my vision. Things get tweaked and changed and improved and polished and sanded. But I give the editors and designers a full idea because it’s about the flow and experience of reading it. And the rhythm of it, so the pictures are as important as the words.

Did this book closely align with your initial concept?

Blakeney: I would say it’s kind of like when you’re designing a home and you create the vignettes of the room and the floor plans. And then you go into the room and move the furniture in and put the wallpaper up. It looks like the vision, but there are always things that don’t fit quite how you imagined, or you might have to switch out a nightstand or a plant because once you get it in there, it didn’t have the right feel. So I think it’s akin to that, where you can plan, plan, plan. And then when it actually happens, things get tweaked or changed in a way. But it does, at the high level, fit the original vision.

Max, you mentioned to [Business of Home editor in chief] Kaitlin Petersen in your episode of the Trade Tales podcast that you found the writing really challenging. How did you get into a groove with your co-author?

Humphrey: In the beginning, I submitted a pitch, and it was pretty wordy. And my editor said, “You're going to edit this way down.” She was nice about it, but the more I thought about it, [she] was right. I didn’t want to over-explain stuff. My book is not organized by project. My book is more of an A-to-Z, and once I wrapped my head around that, I was like, ‘OK, this is a picture book.’ And there are captions and blurbs where I can talk about specific products, projects or the history things.

But writing is so hard. There’s so much bad writing out there. I basically spoke the book and Chase transcribed it, and then we bounced it back and forth. After that, it was all about editing it down.

Do you think there are already enough design books that present a designer’s 10 greatest projects and something about the homeowners?

Humphrey: Someone is going to do that better than me anyway. I taught myself how to be an interior designer by reading interior design books. That’s one of the reasons I wanted to make one, because I feel so indebted to interior design coffee table books [I’d read at] Barnes & Noble.

When you buy one cup of coffee and sit in the store for four hours?

Humphrey: Yes, like squatter’s rights at Barnes & Noble. And reading back some of the books that I responded to, I wanted mine to be accessible. The book wasn’t about me getting new clients from a business perspective. The goal wasn’t, “I’m going to put out the most high-end work so only millionaires hire me.” It was about being accessible. I wanted the writing to reflect that and the text to sound like me talking. There was a lot of back-and-forth with my editor, [who told me], “You say ‘like,’ instead of ‘such as’ throughout this whole book. I’m going to have to go to bat for you with the other editors.”

Max, your voice in your book really comes through. We get how you talk, how you joke, where you would be serious on a job site, where you’d be cool to shop with. Justina, the tone in your book was so intimate and personal. How did you decide the tone you wanted to take in this particular book?

Blakeney: Making the book more personal was definitely a conscious choice and came out of the fact that I’ve spent the last 12 years having a voice online as a blogger. And on my blog, I always mixed design ideas and inspirations with personal anecdotes and stories of who I am and where I’ve been and how that’s influenced my aesthetic. When I came to this idea of doing a Jungalow book, what it really boiled down to was who I am. The Jungalow came out of me because of who I am—what I love, how I was raised, the particular cultural mix of my background growing up in Berkeley and the places I’ve traveled and the things I’ve seen in the people I’ve met along the way. All these things had an effect on me being able to build this brand. So I wanted that to come through in this book.

My last two books were a lot more outward-facing. I was going into other people’s homes. I wanted this one to be more about me sharing sides of myself that I may not have shared. The way that I teach is to share my experience. Instead of saying, “You do this, you do that,” I say this: “This was my experience.” With this book, I didn’t want to be prescriptive. I wanted to tell a story.

Both of you help to demystify aspects of design, and there are a lot of voices in that space now. Do you feel like there’s more to add to the conversation?

Blakeney: For me, I’m interested in the empowerment piece. So many people over the years have said things to me like, “I’m not creative. I can never pull that off.” I think a big part of my mission is just to help people find their creative spark, to help them nourish that and turn it into a flame. And that’s what my book is trying to do. It’s showing how to look at basic things in a new way, to see a space in a new way, to look at anything as material, to invite color into your home in ways that help you shed fear and tap into who you are.

I think a lot of folks lack high-level creativity and confidence when it comes to design, because historically it’s been positioned as an elitist thing that only certain types of people have access to or understand. Some people have an eye, and some people don’t. Some people are creative and some aren’t. I reject all of that. For me, it’s about helping people build the confidence and giving them some tools to be able to tap into their most creative selves and express themselves in a way that helps them create a home that supports their growth, their well-being, their family and their dreams.

Humphrey: Creative confidence is the big thing with interior design. If I’m speaking to up-and-coming interior designers, there’s a business confidence you have to have. You’re asking people for money and sending them an invoice and sticking up for yourself. When I first started out, I had to deal with these hotshot clients that were used to bossing assistants around and stuff. You’ve got to be confident when you’re sending an invoice off and saying, “Yeah, this is how much it costs, and you need to pay this because I’m out-of-pocket.”

It’s interesting that both of our books are in the DIY category on Amazon, and there are no step-by-step processes [in our books]. I don’t learn that way. I learned by doing. I didn’t know what I was doing getting into the interior design industry. I just had to get in, do it and start decorating. It was my own apartment at first and then other people’s. But I want to teach that everybody can do it: Everybody’s creative, everybody’s an artist, but not everyone is confident. When I told Kaitlin in my podcast interview, “I don’t want people to hire me again,” the point was that I want them to be like, “OK, we can do this next time. Thanks.”

It’s like a therapist—really good therapists don’t want to see you forever. They want to help you so that you can get where you need to go.

Humphrey: I always tie it back to music. You could take guitar lessons forever, but that doesn’t mean you can be in a band, you know? I think about punk bands that didn’t know how to play. The Ramones didn’t know how to play, and they booked their first show. The Slits didn’t know how to play, and they’re the greatest of all time.

Borrowing the punk rock idea, there’s a kind of anti-establishment quality that you both bring to what you do. Which is not to say you don’t know the rules.

Blakeney: I don’t know the rules.

Humphrey: I know the rules.

With this notion of giving people confidence, are you consciously using words and descriptors that are approachable? Are you formatting the book a certain way so you can convey that?

Humphrey: In terms of the language, yes.

And with the organization and format?

Humphrey: There was a conscious decision to not make it like every other book—both to be different and because that’s what I would want to consume. I’m not there yet in my career to put out a coffee table book that says, “Here are my 15 best projects.” I don’t want to read that book, and I also don't feel like I’ve quite earned that. So part of it was asking, What’s the concept here that's different than everything else?

From a language standpoint, I basically went through and took out all the adjectives. That was the trick for me to make it accessible and readable, because I would never say some of those words. I don’t use a lot of adjectives in my day-to-day, so that was an easy grammar exercise. Aesthetically, I want more and more. More color, more patterns. But when it came to the words, I wanted to edit them down to the minimum.

Justina, you almost create your own language in the book with your pairings of cultures and styles that seem like disparate influences. That concept was more than you saying, “Let’s do a mashup.”

Blakeney: There were a few things at play there. One is that culturally, I am an unusual mashup: I’m mixed Black and Jewish, and I grew up with these very disparate cultural influences, blending very seamlessly in our household. It was a regular thing to have matzah ball soup and collard greens. For me, mixing unusual things together is in my blood. It’s who I am. I’m not the first person to put things from different cultures together—in the design world, that’s ubiquitous—but what I feel like isn’t always done is honoring the places and the people where these pieces come from.

Part of what I love about design, makers, artists and artisans is learning the stories. And I really wanted to help tell some of those stories in the book and for it not just to be about how cool this room is, how textured or “cultural” or “ethnic” it is, but really about saying, Look what happens when I consciously blend Moroccan art with pieces that remind me of my childhood in California. I think as designers, we incorporate these things because we sort of viscerally feel how cool they are. And I’m always trying to dig a little bit and figure out the why: Why do I think this is cool? What is it about it that’s drawing me in? With my like boho, layered style and things I’m pulling in from different cultures, I just wanted to understand a little bit more about the why.

Max, you sort of do something similar with your love of vintage.

Humphrey: I think both of our design styles are informed by our upbringing. I’m from New England and I spent 20 years trying to scrub every preppy layer off of me. But now, looking back as an adult, every design decision I’m making is about how I get back to this childhood. It’s an aesthetic and nostalgic pursuit—it’s like there’s a visual [element accompanying] the warm memories I have of childhood. When I think back, there are these patterns and textures and objects and materials that I was surrounded by as a kid, getting dragged to antique stores [with] blue plaid sofas.

The point is: There’s a nostalgia [in] both of our styles. Justina talks about her family a lot, and I do too. And it’s interesting because we don’t have the same styles, but we both have this aesthetic connection to family and childhood.

Blakeney: I also think we think we both geek out on vintage. We're both like vintage hounds.

Humphrey: Totally. It’s not for everyone. I’ve taken clients vintage shopping and they’re like, “Don’t do this again.”

Blakeney: It’s not for everyone, but I love it so much. I love the stories, the history, the personality, the conversations and the weird. I just love the weird shit.

Max, what surprised you about making your first book?

Humphrey: A book is a full-time job. I didn’t know what to expect, but it’s more work than anybody tells you.

Blakeney: Hard agree.

Humphrey: I had a very short timeline. It happened very fast. I signed my book deal, and I had to plan a pandemic summer’s worth of photo shoots. I didn’t want to regurgitate every photo I’ve ever taken. I wanted new stuff, too. And I wanted to strike a balance between personal anecdotes, how-to content and stories behind objects.

I made a list of objects and themes and patterns and fabrics that I wanted. I had a big list: vintage rugs, lamps, Buffalo check, plaid, grain sacks. Once I had that list, I was like, What do I need to shoot? Where can I shoot it? Do I even own this stuff? Do I have to go shopping? I signed the deal in June and turned in the second half of the photos in August. It was so much faster than I was expecting.

Blakeney: That’s an unusually quick timeline.

Humphrey: It was good for me, because if they said you have a year, I would have taken a year. If they said you had three months, I would have taken three months. So having it a finite amount of time was good for me. It trumped other work. I have to earn a living—books aren’t necessarily money-makers for interior designers; a lot of time they’re marketing tools. So I had to work throughout all of this. I would say the book was my full-time job in 2020, and my side job was being an interior designer. I feel very lucky to be able to say that, because I was able to focus on it and juggle family life and other things. I don’t have a crew. It was me and my photographer, a writer and the publishing team. But I can’t imagine doing it any other year.

Justina, how was the production process for you?

Blakeney: I have been working on this for two and a half years. My manuscript was due the week that the world shut down for COVID, and this book was a way bigger project and more intense than my last two books.

Humphrey: On purpose?

Blakeney: Not on purpose, just because it was so much more personal and all the work is mine, as opposed to me going in and styling other people’s homes, which is a lot easier. This was a big job.

It took two and a half years, and I felt such a sense of relief once I handed in the first draft. It felt so good. I’m like, Ah, I’m done. I can focus back on my business and my kid. And then, of course, as you can imagine, the editing was intense. So I was really working on the second, third, fourth, fifth drafts until about September. There were another six months of work that went into it. And at that point, I was like, It’s done. I handed them a Word document, a Dropbox file with 500 pictures, and an InDesign file with the whole book laid out.

By the time it came out in April, I was nervous because I had been in my house for the past year, wondering, “Is this relevant?” I was really pleasantly surprised with the response that we’ve gotten.

Humphrey: Do you go back and read your book?

Blakeney: I read it when I first got it. But I have read it so many times, because the editing process was so much harder than the last books. Then another four or five months goes by between the time it’s totally done and to print. And then, you know, you get the finished book in your hand.

Humphrey: I couldn’t even open my book when it first arrived. It’s a little weird. Maybe you were like that with your first book—it’s like hearing your own voice.

Blakeney: I totally get that. And, you know, I get that way with my work sometimes, but I think the books are such an epic project. It’s just so packed with so many different sides of myself, it does make me vulnerable. But when I look through it, I don’t see myself. I see my team and my husband who co-wrote the book with me, and all the experiences that we had together creating it. So I just feel a lot of pride, and I’m excited to be putting this stuff into the world.

You mentioned the anti-establishment thing, and I don’t necessarily feel like I’m anti-establishment, but I’ve always felt rejected by the establishment. I’ve always felt like, Oh, you’re a blogger, you don’t fit into this or that. So I feel very proud of these kinds of projects for all the people who don’t feel like they fit in—not just the design world, but whatever establishment they have felt rejected from. Having this book and a community of folks who are allowed to be themselves in their homes and express themselves how they want—that’s what I want from my book. That’s what lights me up and gets me excited.

So I’m anti-establishment in the sense that, after feeling somewhat rejected by the design establishment, I had to just say, “Fuck it. I’m going to build my own community. I don’t need to tap into yours.” In that sense, the book is very empowering because I’m able to say, “I built this myself, and you can do this too.” I think that message is an important one in the design world and beyond: “You might not fit in, and that’s your superpower.”

Humphrey: For me, the book response is such a different feeling than other press I’ve gotten. People reach out after you get magazine press and say, “We saw this in a magazine. We want to hire you,” or “We saw this in a magazine, and I want to know where these barstools came from.” The response from the book has people reaching out to me who don’t want anything.

Blakeney: They’re reaching out because they’re moved.

Humphrey: Yeah, or they tell me they feel seen in their decorating choices. It wasn’t, “Hey, cool book.” They don’t want anything.

Blakeney: Well, they already got it.

Humphrey: They got it. And now it’s for them to use.

Homepage image: An interior featured in Decorate Wild | Courtesy of Jungalow