A prediction: In 10 years, we’ll look back on this time as the last gasp for trade exclusivity in the interior design industry. It’s been a long time coming. Thirty years ago, interior designers were the lone gatekeepers to a walled garden filled with the world’s best product. Over time, the openness of the internet has chipped away at those walls, brick by brick. COVID has only accelerated the trend, as brands and makers (even custom makers) have scrambled to get their businesses online. Whether they’re selling through an open marketplace like Houzz or Perigold or their own Shopify site, once the genie is out of the bottle, it’s not going back in. Eventually, everyone will be able to buy everything.

The good news is that interior designers—who have learned to sell their artistry instead of their access—may never have needed trade exclusivity in the first place. But there’s no denying that the openness of the internet has put designers on their heels in conversations about markups and pricing. Lynsey Humphrey, a Park City, Utah–based interior designer and entrepreneur, has just launched a new digital platform, SideDoor, which she hopes will level the playing field and put designers back on the front foot in this new era.

“In the last five to 10 years, we’ve seen an influx of e-tailers that have signed up the vendors that are supposed to be selling [exclusively to] us,” Humphrey tells Business of Home. “Designers are tastemakers in every community locally and nationally, they have big followings on Instagram—then they get circumnavigated and shopped. That shouldn't be the case.”

There are a few different ways that designers can use Humphrey's platform. The most basic: as a huge digital multiline showroom. Designers can apply for access with a resale number and business license, and once they’re in, they can browse product (with listed designer pricing) from over 150 vendors, ranging from Universal to Caracole to Stark Carpet. Transactions are one-click, and SideDoor manages shipping and delivery.

Giving designers access to a wide variety of trade-focused brands, many that would normally require minimum orders, was reason enough to start the company. “Most of the industry is one- or two- or three-person studios that don’t have that buying power [to meet minimums], or don’t want to pigeonhole their buying into one vendor,” says Humphrey. “As a designer, I was always having to call a vendor and negotiate and say, ‘Hey, I’m worth taking a chance on.’”

However, SideDoor’s buzziest hook is a series of tools that allows designers to curate a selection of products, sell them on their website or social feed with shoppable links, then pocket the difference between designer pricing and the retail price. It sounds simple, but the implications are profound—especially for e-designers or those who want to turn a robust social audience into a revenue stream.

Take, for example, a designer who wants to sell an e-design client (or a follower on social, or a visitor to their website) the Taylor nightstand by CFC Furniture, a product that’s available to the public on a variety of e-commerce marketplaces for about $1,600. If the designer provides the client with an affiliate link to purchase the nightstand through a big marketplace, they’d be lucky to earn a commission of 7 percent, or roughly $112. If the designer goes through SideDoor, they’d make the difference between designer pricing and retail, or a little over $400. Same product, same sale—but almost four times the profit.

Humphrey, who is self-funding SideDoor, says the company earns revenue by buying from vendors at showroom pricing tiers. Though initially she considered a monthly membership fee for designers, her intention is to keep the platform free.

The tantalizing prospect of putting together a compelling digital mood board, inserting a few links, sitting back and raking in 30 to 50 percent profit on whatever sales roll in, says Humphrey, has already enticed 5,000 designers to set up a SideDoor account since its launch in early September, who have begun pushing through hundreds of sales.

On the vendor side, 150 brands currently sell through the site, and Humphrey is adding more as quickly as their data can be formatted. (She says getting the inventory and datasets of various brands’ systems to all work in the same program has been her 12-person staff’s biggest challenge thus far.)

“[A lot of these] vendors didn’t really want to have to go online. They liked the old way of selling, but they saw this onslaught [of large e-commerce marketplaces] and thought, You know what, if designers and brick-and-mortar is going away, we’d better shore up,” says Humphrey. “However, we’re not approaching vendors with your typical, ‘Hey, get on e-comm!’ request. Our approach is: ‘This is who we are, do you want to participate?’ If they do, they’re much more apt to give us the resources we need.”

The site’s tools essentially replicate the structure of classic 20th-century interior designer transactions, but applies them to 21st-century e-commerce and affiliate marketing models. There’s a lot of nuance and complication in making that happen. For example, SideDoor shows clients a retail price that includes freight costs, meaning its displayed prices are often a bit higher than at its e-commerce competitors, who frequently absorb the cost of shipping. However, the site automatically strips branding and product names from its listings, making it more difficult for clients to “shop,” even if they’re so inclined.

There are challenges and limitations to the platform. A big one: SideDoor doesn’t offer returns. That alone may scare away some potential clients, though the designers who spoke with BOH with said the site’s service was excellent and that they were able to get questions about product answered easily.

Additionally, SideDoor doesn’t allow designers to set their own pricing—users aren’t allowed to charge their clients over or under the “retail plus shipping” price automatically generated by the site. The platform also doesn’t sell custom product, and though it covers a good range of price points, most brands are clustered toward the middle—users won’t find too many extremely budget options, nor is it rife with $15,000 sofas.

Finally, as the site is still in its early days, its interface and tools are still being finessed. From an end-user perspective, SideDoor doesn’t yet resemble a hyperpolished corporate e-commerce site. However, it’s (very) early in the site’s life, and Humphrey and her team are listening to feedback from designers and tweaking the user experience accordingly.

BOH spoke with three designers who had used SideDoor as part of its early launch, all of whom happened to focus on e-design as a core aspect of their business. It’s easy to see how appealing the platform would be for e-designers, who tend to work by devising a design scheme, then having clients purchase product themselves. In e-design, most of the revenue is made on per-room fees, and designers are lucky to pick up a few dollars here and there with affiliate links. Earning a trade margin on product could easily double their profit.

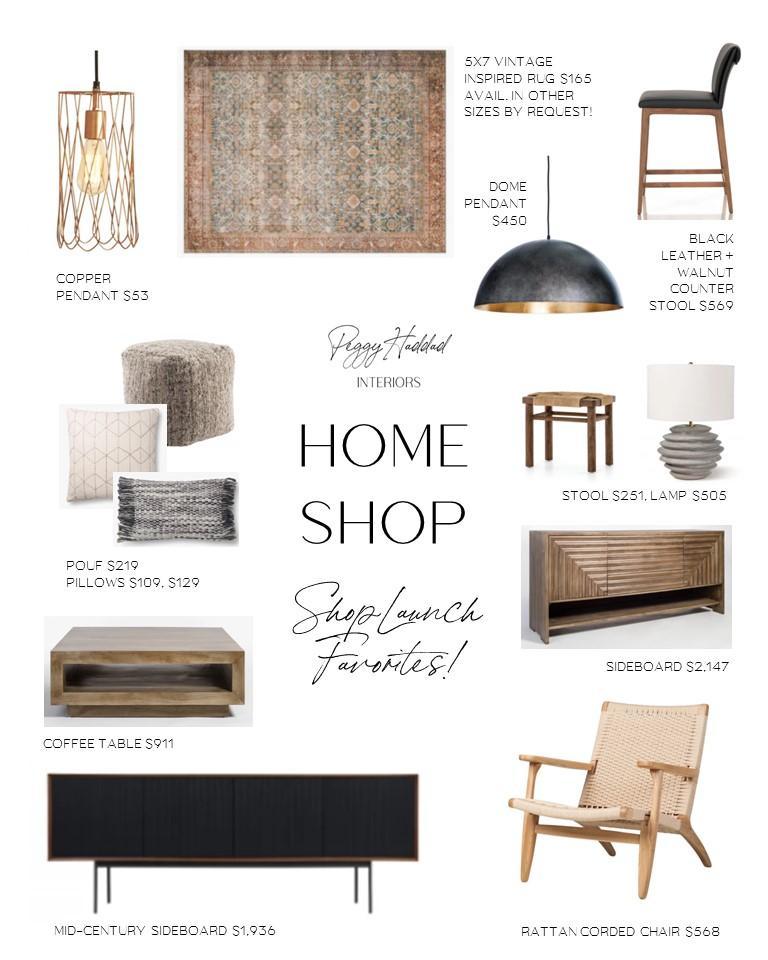

“I’ve used SideDoor for two projects, and the percentages are so much higher,” says Peggy Haddad, a Denver-based designer who focuses on virtual design. “It’s really big for my business—a game-changer. Typically, I would give clients a shopping list that was all retail. There are retailers out there who sell trade product, but the retailers are the ones who’d get the commission.”

Interestingly, the designers I spoke with seemed as much energized by SideDoor’s mission as its potential. Humphrey, who speaks with an infectious “we’re all in this together” energy about the design trade, has clearly struck a nerve.

“With the internet and HGTV and Wayfair, and these huge conglomerates, they’re using our talent, but we’re not reaping any of the benefits,” says Vanessa Wolf, a Seattle-based designer who does both in-person and virtual design. “You can get shopped any day of the week, and even when you do earn [an affiliate commission], you’re only getting a tiny percent and the rest of it is going to a big corporation. ... The bottom line is we as designers need to innovate.”

Homepage photo: Shutterstock