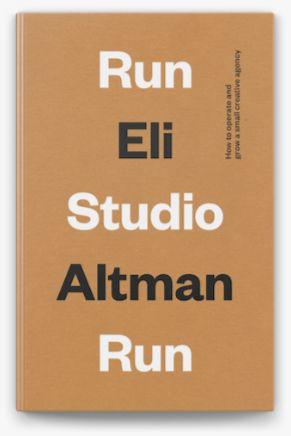

Designer Stephanie Sabbe purchased dozens of business books, but never came across one that she could actually get through. Then she found Eli Altman’s Run Studio Run.

While there are countless ways to approach leading a firm, industry insiders have long agreed that design schools often fall short when preparing students for the realities of entrepreneurship. After all, running a design business is just that—business. To compensate for this, Stephanie Sabbe has self-educated through business books since founding her Nashville design firm in 2010—and the one that stands out from the crowd is Run Studio Run, written specifically for entrepreneurs in charge of creative studios with 20 employees or fewer.

Run Studio RunCourtesy of Eli Altman

Ready to dig in?

This article is available exclusively for

BOH subscribers and BOH Insiders.

BOH subscribers and BOH Insiders.

Want full access?