Five years ago, a client became enamored with the photorealistic renderings she spotted on a real estate pamphlet and asked Seattle-based designer Jessica Dorling to provide one to help her visualize a living room design. There was just one problem: A high-quality rendering can cost upward of $1,500, a fee most designers pass on to the client. This one ultimately chose not to pay for it. “I could never get clients to invest in that,” says Dorling. “You could put that $1,500 toward so many other more impactful things.”

Renderings were, and continue to be, a hallmark of the luxury residential and commercial real estate experience. And many designers find ways—often working with overseas vendors—to deliver them more affordably. But they are still an expense that many clients push back on. AI may fundamentally change that dynamic now that generative image tools are making it easier, faster and cheaper for anyone to create renderings from the comfort of their own studio (or home office, or taxi ride). The possibilities are as endless as the prompts. Though platforms like ChatGPT, Midjourney and Nano Banana notoriously struggle with scale and accuracy—especially when it comes to patterns, textures and three-dimensional floor plans—they are growing more sophisticated every day. They are also growing in popularity among designers, who are increasingly employing those generative models during the design process to help clients imagine what a space might look like with, say, a large-scale mural on their dining room walls, or a boldly repeating fabric on their living room sofa.

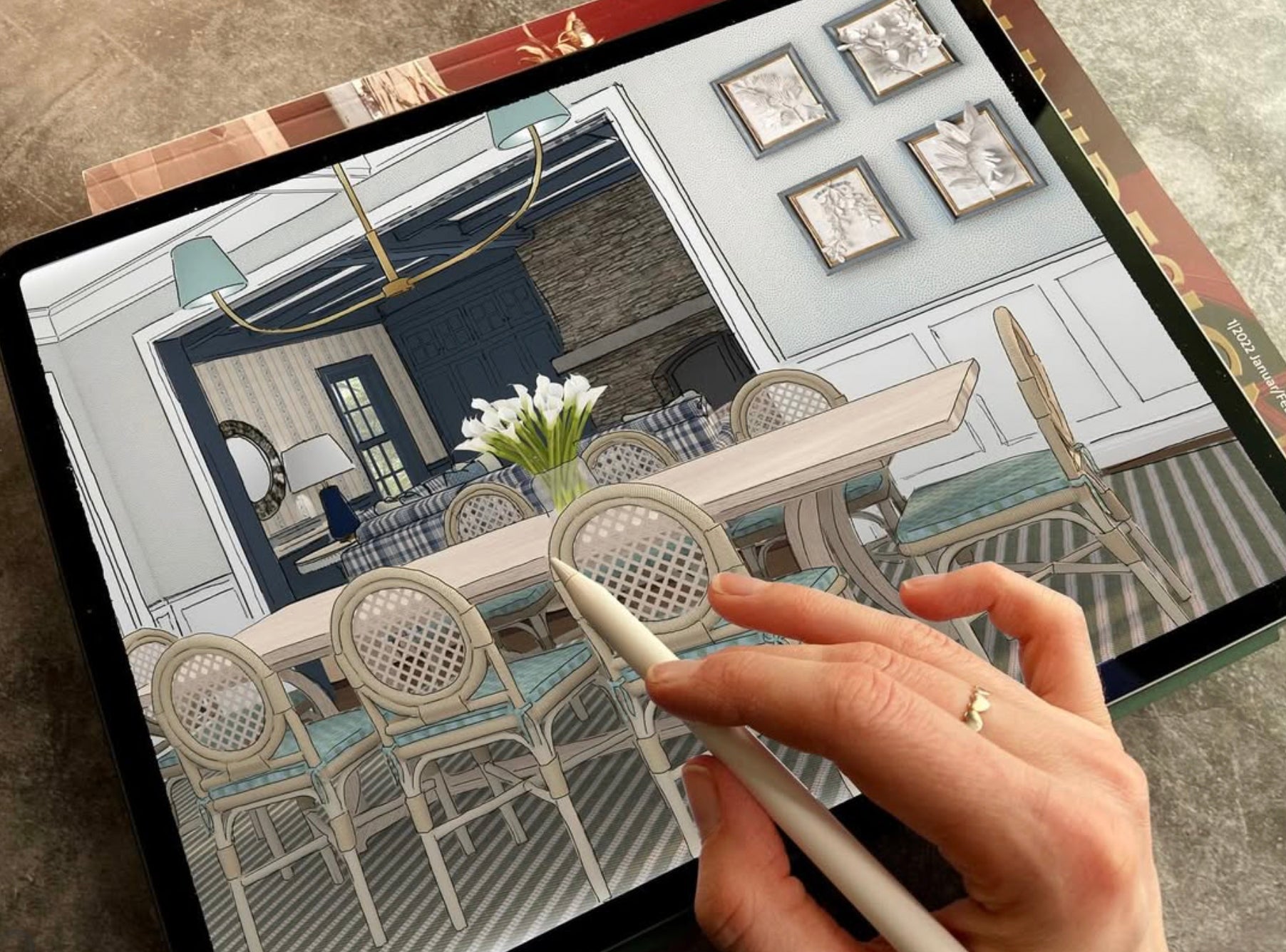

“It’s a game-changer for me,” says Dorling, who has experimented with ChatGPT over the last couple of years. “No matter how much you explain something to a client, things can be lost in translation. If you can provide a visual, it takes all the ambiguity out of the conversation.”

Adds Ridgewood, New Jersey–based designer Kristina Phillips, who also uses ChatGPT: “It’s an extremely valuable tool for visualization. In the past, if a client wanted to see what a specific wallpaper looked like in a room, I would have to go on Pinterest or Instagram or the manufacturer’s website to see if there was an image I could show them. Sometimes there was nothing out there. If they get the technology to where it looks better and more professional, I would use it for every room.”

Given the meteoric rise and industry-wide embrace of generative image tools, if designers—and clients—are now creating their own room sketches and AI-generated photos, what happens to the businesses that specialize in renderings?

Jenna Gaidusek, a Charleston-based designer and the founder of the consultancy AI for Interior Designers, says that the technology has not advanced to the point that designers can use AI for technical drawings or floor plans. However, for simply getting an idea across to clients, it’s good enough. “For the visual parts of a presentation where you don’t need the accuracy, [renderers are] already being phased out,” she explains. “I haven’t rendered for a client in almost two years. Traditionally, firms have paid thousands of dollars to get one or two images of their concept to be able to sell it to the client. Now we can do that in 90 seconds and show clients three views on the spot.”

Gaidusek has developed a proprietary AI design app, but she also relies on a multistep process, feeding mood boards, floor plans, and Canva-created images layered with actual products, plus prompts gathered from client meetings and concept presentations, into Nano Banana. (Dorling also uses Canva-generated images to improve ChatGPT’s performance, and stresses the importance of exceedingly specific prompts to achieve better, more realistic results.)

Of course, human renderers have a preferred place among the perfectionists, the heavily bankrolled and the technology-averse, but for the designers who commission them, there’s also a rapport, an ease of interaction that amounts to a sort of unspoken design language.

“There’s just so much I know about how these designers make their decisions, and to be able to inform an AI and image generator—that kind of nuance and detail feels like an impossibility,” says Kristi Carré Freeland of the hand-styled renderings she creates through her firm Carré Designs in Boulder, Colorado. “I know that, like, designer A always prefers 1/8-inch grout lines, whereas designer B likes to play around with the size of their grout lines depending on the project. There’s just too much precision involved. And that’s what our clients pay us for. They come to us not to be the imagination that AI can come up with, but to be a really precise team member that communicates things clearly to the rest of the parties involved.”

There’s also a learning curve: It takes time and effort to master prompting AI tools to achieve the kind of image that might replace a rendering. Plus, some rendering agencies are already putting processes in place to incorporate AI into their own workflows. “A lot of our designer clients just don’t have the time or energy [to] learn all of that on their own, in addition to everything else that they’re doing,” says Carré Freeland. “I don’t know how high the motivation is to learn it when they can call us and know that we’ve already done that work for them.”

Gaidusek and many renderers themselves expect that AI will ultimately benefit rendering businesses in the long run. Improvements in workflow and project management will not only shorten rendering times and decrease the level of administrative work that goes into creating images, but she says it might allow the agencies—at least the ones who adapt to new industry standards—to take on more clients (for lower rates). “They might lose some lower, entry-level positions as they start using the technology in their workflows, but they already know what they’re doing,” she adds. “They can just reestablish themselves in a different way.”

If that model takes off and more rendering agencies begin to offer AI-supplemented services at lower prices—and if designers start to incorporate AI-generated renderings more fully in their own firms’ processes—a human editor with real design expertise will still be crucial.

“The designers that have been doing this in the real world for a long time—those are the ones who immediately know when something looks off,” says Gaidusek. “I’ve been posting this type of stuff on my Instagram since 2023, when it was really, really weird, and the ones that comment and take out the things that are really odd that nobody else sees—those are the designers. Those are the ones with the critical eye, because they’ve been trained. It’s the people that come in as a DIYer or don’t have any formal training that wouldn’t be able to see those things. But that’s why you hire a designer in the first place.”

On the other hand, that could be why designers hire a renderer in the first place. “I do think that at the high end of the market, there’s still always going to be this need for the human touch,” says Mickey Mayo of New York–based visual production company Mayo Studios. “There’s a really clever balance that can be struck, where AI and other tools can be implemented to offer efficiencies, but there still needs to be that trained eye or that expert touch to really make a distinctive brand or distinctive product or distinctive design really, really come to life and resonate.”

There’s no denying that the images penned by human hands can more credibly be defended as works of art than those created with tools like ChatGPT and Nano Banana. For that reason alone, there will always be a market for them, especially for those with larger budgets. “I see the value of hand sketches and artistry being this luxury service in a world of AI that is oversimplifying and dehumanizing,” predicts Gaidusek. “When you have artists and people who can sketch, that commands a premium price going forward.”

Additional reporting by Aidan Taylor