Stop me if this sounds familiar: You go to a showroom and discover a gorgeous new furniture line. The silhouettes are stylish and subtle. The craftsmanship is refined. It’s the complete package. You’re sold. You go home to give it another look online, and the brand’s website—all blurry photos, cringe fonts and broken links—looks like it was hastily thrown together in 1996. Why?

It’s almost a cliche to point out that the design trade has not been quick to adopt new technology, especially when it comes to buying and selling online. Often, that’s attributed to cultural inertia. The people—designers and the brands that sell to them—don’t really want to change, so change doesn’t happen. Or so the thinking goes.

There’s probably a hint of truth to that argument, but it overlooks the basic structural challenges of the industry. Selling commodity-like products—light bulbs, socks, even iPads—online is a solved problem. But the trade doesn’t sell commodities. It sells infinitely customizable goods in an extremely complicated way. Amazon has figured out how to move paper towels. But imagine if every customer needed a CFA for their paper towels, and you could get paper towels in any color, shape, size and pattern. Now imagine if customers could place reserves on paper towels. It’s not just a slightly more complex problem—it’s an order of magnitude more difficult.

Of course, it goes without saying that trade brands don’t have the same money to spend on technology that Amazon does. Most are small to midsize companies, selling to a relatively small number of designers, who themselves may not be digital natives and have no desire to shop online.

The resulting landscape is this: Getting e-commerce right for interior designers is more complex than it is for general consumers, the demand is less, and the resources to meet that demand are fewer. Is it any wonder that change comes slow?

That doesn’t mean it won’t come. Wise to the fact that the rising generation of designers will expect them, trade brands have begun to more seriously invest in e-commerce tools in recent years. At the same time, off-the-shelf solutions have gotten more adaptable, and a host of marketplaces have sprung up to fill in the gaps. We’re in the midst of a slow-moving but undeniable shift: The trade is figuring out how to do business online. It’s complicated.

THE ONLINE LANDSCAPE

Holly Hunt’s website didn’t exactly look like it was made in the mid-’90s, but until recently, it’s fair to say that one of the trade’s most respected brands didn’t have a digital presence to match. The Chicago company was already in the process of a revamp, but when president Marc Szafran joined at the outbreak of COVID last year, efforts to roll out a new and improved Holly Hunt website were “turbocharged.”

“[At the outset of the pandemic], the need for what e-commerce can bring to the table became amplified,” Szafran tells Business of Home. “The website needed to reflect the look and feel of the brand, but the most important thing was: How can this be a tool to enhance what we’re already doing?”

The new site, which debuted earlier this year, is a testament to both the opportunities and the complexities of doing business to the trade online. In place of a static product gallery, there’s now a dynamic marketplace that allows designers to browse and purchase in-stock product online (that’s after logging in with a trade account—the site anticipates designer anxiety by clearly advertising that “online purchases are limited to design professionals”). In the broader world of online commerce, it’s nothing out of the ordinary. But for a brand that has spent decades oriented around selling through showrooms, that’s a significant leap.

Szafran says that Holly Hunt has seen an increase in new accounts through the site, and a significant spike in in-stock shopping (up 70 percent for furniture and 52 percent for accessories). So far, the numbers suggest the investment in the website is paying off. But it’s worth noting that Holly Hunt has started by selling in-stock furniture and decor only. Soft goods, made-to-order and custom product—all crucial elements of the company’s business—are yet to come. Szafran says this is because custom goods are infinitely more complex to spec online, and the brand was hesitant to debut the functionality before it was polished.

For example, Holly Hunt is working on a configuration tool for custom furniture—easily the most complicated product to sell online—but Szafran says it’s too soon to say when it will roll out. Even soft goods, debuting over the next few weeks and ostensibly a simpler sales process, take a ton of finessing to sell properly to the trade. Reserves, CFAs, up-to-the-yard stock—these are all complicated functionalities. Dye lots, he says, were a unique challenge to overcome; Holly Hunt’s forthcoming tool allows designers to ensure the color is consistent across different bolts of the same fabric.

Whatever the product, designers need more information than consumers do to make a purchase, which presents a challenge for brands in the trade. Of course, every challenge is an opportunity in disguise, and the demands of selling to designers have led to a lot of compelling experimentation.

Kravet, hardly a newcomer to the e-commerce game, long ago rolled out the core functionalities designers buying fabric require (stock availability, ordering samples, etc.), but in recent years has implemented some intriguing features. For example, designers can search the brand’s stock by a complete color palette, adjusting a series of sliders to dial up options that fit the bill. (Looking for fabric that’s 50 percent pale green, 50 percent light blue? Kravet’s site coughs up 270 options.)

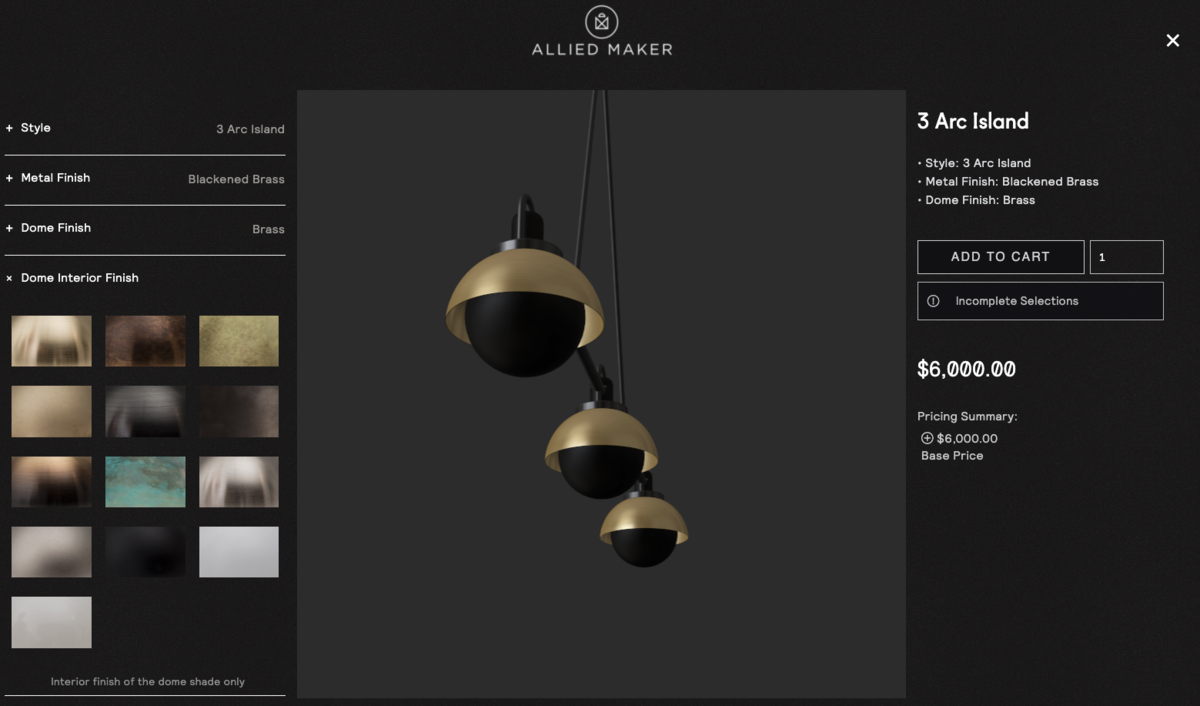

Much of the seriously cool tech in designer-driven e-commerce is based around visualization. Though Allied Maker, a Long Island–based lighting brand, is a relatively small company, it boasts some remarkably advanced configuration software. The site allows users to design a 3D model of a fixture in real time, which can be digitally rotated for inspection before purchasing.

It’s a sleek tool, designed for professionals but branded and executed in a way that feels more like something you’d come across in the world of consumer luxury. That’s intentional. “We really wanted to be the company that you come to and our tools are just so much better than anyone else’s that you keep coming back,” says co-founder Ryden Rizzo. “Way more people are going to visit our website than our New York showroom. It had to be perfect.”

Of course, not all e-commerce technology has to be this impressive to be useful. For many brands, developing a shoppable website is less about sophisticated tech and more about reaching new customers, or simply meeting their existing customers where they are.

Saltwolf is a prime example. Started in 2020 by Lindy and Jordan Williams, the Boulder, Colorado–based brand has no showroom representation and no traveling reps—it mimics the basic business structure of a direct-to-consumer company, but to the trade. The bet, says Jordan Williams, is that forgoing the classic model will allow the brand to reach designers in thriving secondary or tertiary markets that don’t have a robust network of showrooms.

“We’ve had this recognition that there are a lot of designers doing great work with great clients on great budgets who don’t live in a market that orbits around the design world as we know it,” he says. “There’s a customer base working in what we call ‘under-resourced geographies’ that’s willing to give us a shot.”

Somerselle, a digital-only multiline started in 2020 by New York–based entrepreneur Anderson Somerselle, doesn’t have a showroom either. Somerselle, something of a digital evangelist‚ left behind a role at a more traditional fabric showroom partially because higher-ups wouldn’t invest in better e-commerce tools. “If people aren’t thinking about the digital future, it’s a recipe for closing your doors,” he says. “People have fully embraced e-commerce. The way that interior designers start to shop for inspiration is on Instagram, and from there, they go to people’s websites. If your website isn’t user-friendly or shoppable, you lose traction.”

Somerselle, the site, is his bet on that future. His platform is based less on cutting-edge technology and more on the functionality that drives day-to-day business. “Designers want to be able to order samples and check pricing without having to go back and forth over the phone or wait for an email,” he says. “Making that work online is not so complicated, and we can do reserves and CFAs as well.” Though he is toying with opening a physical location, the traction he has generated so far has convinced Somerselle that he has space to grow working online-only for now.

ROADBLOCKS

With the opportunities come significant challenges. The first is building a website. The biggest issue there is that most off-the-shelf solutions are built for consumer e-commerce, not for the trade. That’s especially true as brands look to integrate the front end of their site with a complex production process. The really hard stuff is often invisible.

“All the software out there, all the consultants that are supposed to know everything about e-commerce software and ERP [enterprise resource planning] software—they are not equipped to handle [high-end custom] furniture company needs. There’s no one who knows how to set it up,” says Rizzo, who estimates that Allied Maker spent $300,000 on its site, to say nothing of the hours he and his team put in. “We turned our software upside down to make it work for this industry—we customized everything. It was definitely a challenge.”

That’s especially true if brands are looking to build a custom website from scratch. Szafran declined to specify how much Holly Hunt has spent on its site but indicated it was as high a priority as its new blockbuster Los Angeles showroom. Selling to designers is generally not as cheap as selling to consumers.

It’s also not as simple. E-commerce works best when it’s frictionless. That ethos is fundamentally at odds with the way the design trade works. When Saltwolf started to advertise on Pinterest, Williams says its ads were routinely flagged by the platform. The reason? Saltwolf requires a trade account to log in, and Pinterest’s algorithm is skewed against a site it views as having a clunky user experience.

Brands are also faced with the tricky decision of whether to display retail pricing to browsers before they log in with an account (Saltwolf does, Holly Hunt does not)—standard practice in e-comm, something of a third rail in the industry. The rules of the open internet are often at odds with the customs of the trade.

That may not change anytime soon. The good news is that on a modest scale, it’s getting increasingly easier to tweak off-the-shelf solutions for the peculiarities of the design trade. Somerselle, like many boutique brand owners, simply tweaked Shopify templates to fit its needs. There are remaining technical challenges to work out (organizing the disparate inventory data that comes in from his represented brands is particularly knotty); still, Somerselle says the process was not overly complex and cost somewhere in the neighborhood of $15,000.

It’s clear that designer e-commerce is a white space that entrepreneurs are rushing to fill. On the one hand, the Adam Sandow–owned online sampling engine Material Bank recently purchased Clippings, a U.K.-based software tool that is poised to compete with Shopify within the trade. On the other hand, a bevy of marketplace businesses, like SideDoor, Bellvine, Design Trade Services and Daniel House, are all looking to attract brands that would rather outsource the complexity of e-comm to a third party. There will undoubtedly be more tech solutions coming.

Ironically, one of the thorniest problems of designer-driven e-commerce is not technological but cultural. When trade brands go to market, they often rely on a network of showrooms and reps with territorial exclusivity over a particular region. There, too, the nature of e-commerce presents a unique challenge. What happens when a Texas designer buys from the website of a brand (or showroom) based in New York? Does their local rep get a commission? What about a designer based in Texas, working in L.A., buying from a website based in New York—who gets a margin there?

On a boutique scale, these dilemmas can be handled on a case-by-case basis. Somerselle has been working on the honor system, hammering out individual arrangements with partner brands to determine who gets which slice of what. It works. But for large-scale brands, it’s complicated to come up with a single rule that applies to every instance. That alone is a huge impediment to trade brands experimenting with e-commerce—most are locked into relationships that make it awkward.

“That is a bear of an issue, for sure,” says Szafran (partially due to the complexity of territorial agreements, Holly Hunt only sells Holly Hunt Studio online—not the represented brands the company carries in its IRL showrooms). “It is on the list of things we’re trying to work out. … Anything you can do in a more traditional showroom, you should be able to do through our site, and we’d love to be able to roll out e-commerce to rep vendors, but there are some serious practical challenges to making that work.”

It’s possible that over time, territorial exclusivity will erode and new deals will be negotiated. It’s also possible that technology will bend itself to the trade, and sophisticated software will be able to determine whether it was a rep or an algorithm that closed a deal. In the end, whatever’s easiest for designers will likely win the day.

THE HUMAN TOUCH

One interesting commonality: None of the brands interviewed for this piece imagined that even the most advanced e-commerce solutions would ever replace the need for salespeople. There, too, the trade has fundamental qualities that make it resistant to radical change. In the world of consumer goods, a human being doesn’t need to be deeply involved with the purchase of a 24-pack of paper towels. A $24,000 custom fabric order is another matter entirely.

However sophisticated the technology gets, the trade is a human business, based on relationships. Yes, it will get easier for designers to check stock levels, request samples and place orders online. But the infinite complexity of custom and the high stakes of high-end design—where tiny mistakes can cost tens of thousands of dollars—suggests that interior design will always require a high-touch sale.

That’s borne out by the data. Though customers sometimes place orders independently through Somerselle’s site, he says the sales process almost always starts with a personal connection. Rizzo estimates that only 20 percent of Allied Maker’s orders come through its site independent of human interaction. In the trade, a great e-commerce experience doesn’t take the place of a sales staff—it supplements it.

“[Our site] doesn’t replace that one-on-one interaction. It should never replace it,” says Somerselle. “This is a business about relationships; people want to feel like there’s a human on the other end, not a robot.”

Homepage image: © Sodawhiskey/Adobe Stock