It’s not easy to make something as classic as the coffee table book feel new. Which is why it works best when it’s unintentional. For this installment of Open Book, we dive into two new releases—one from an established leader, the other from a new voice—that have reimagined what a design title can be. Approachable, light and fully in command of their purpose, both titles relish the simplicity of a good idea, full stop.

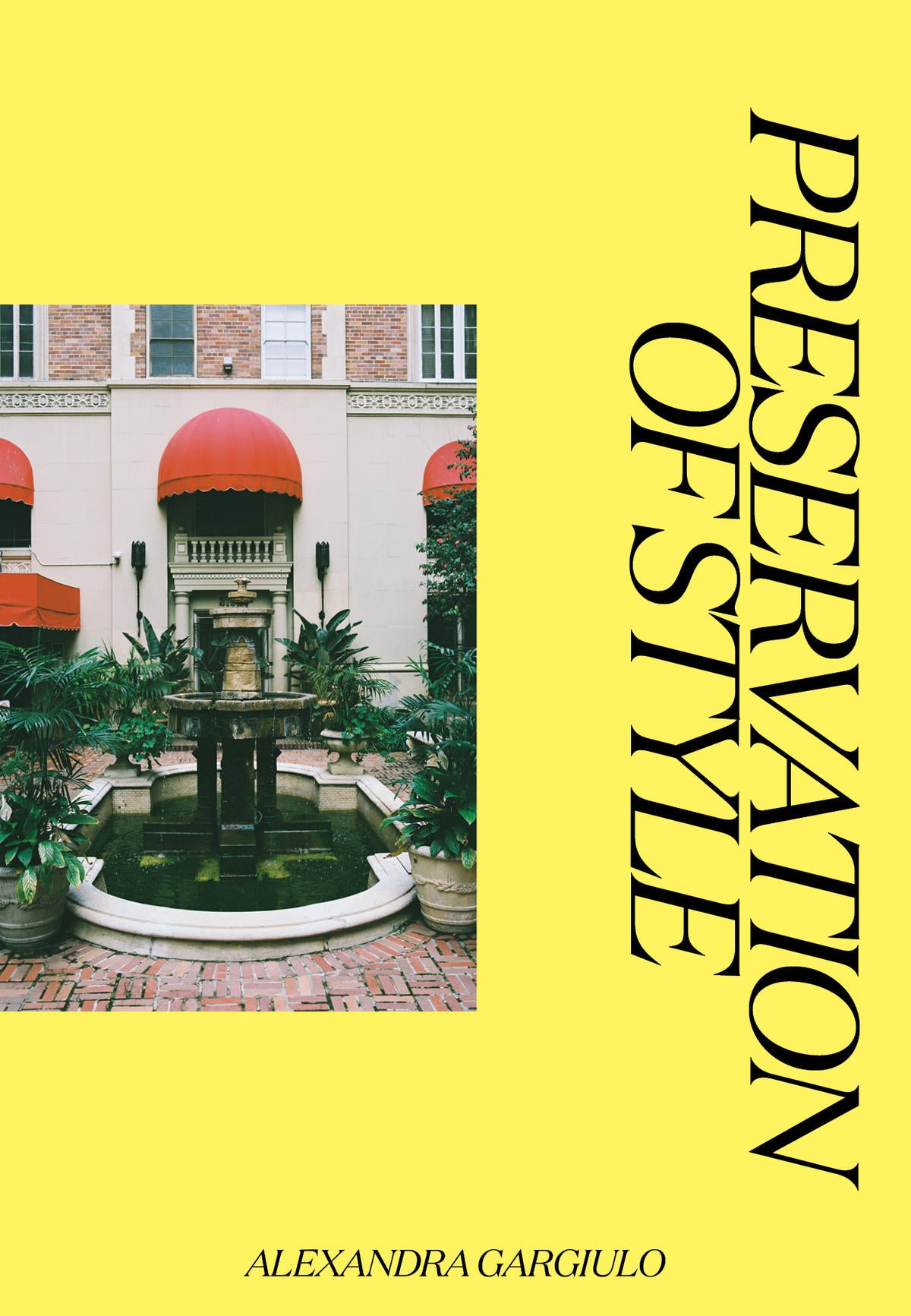

In Preservation of Style, author Alexandra Gargiulo embraces the outsider view in a genre we know so well. A look at three Los Angeles neighborhoods, hers is a visual survey of art deco and revivalist buildings from the 1920s and 1930s. With minimal text and a modern eye, it’s also a self-published project. During her walks to and from law school, Gargiulo would muse about the buildings she passed daily. Now a real estate investor and artist, the L.A. native spent three years researching each property to produce a book that spotlights preservation and timelessness within one of the world’s most seductive landscapes.

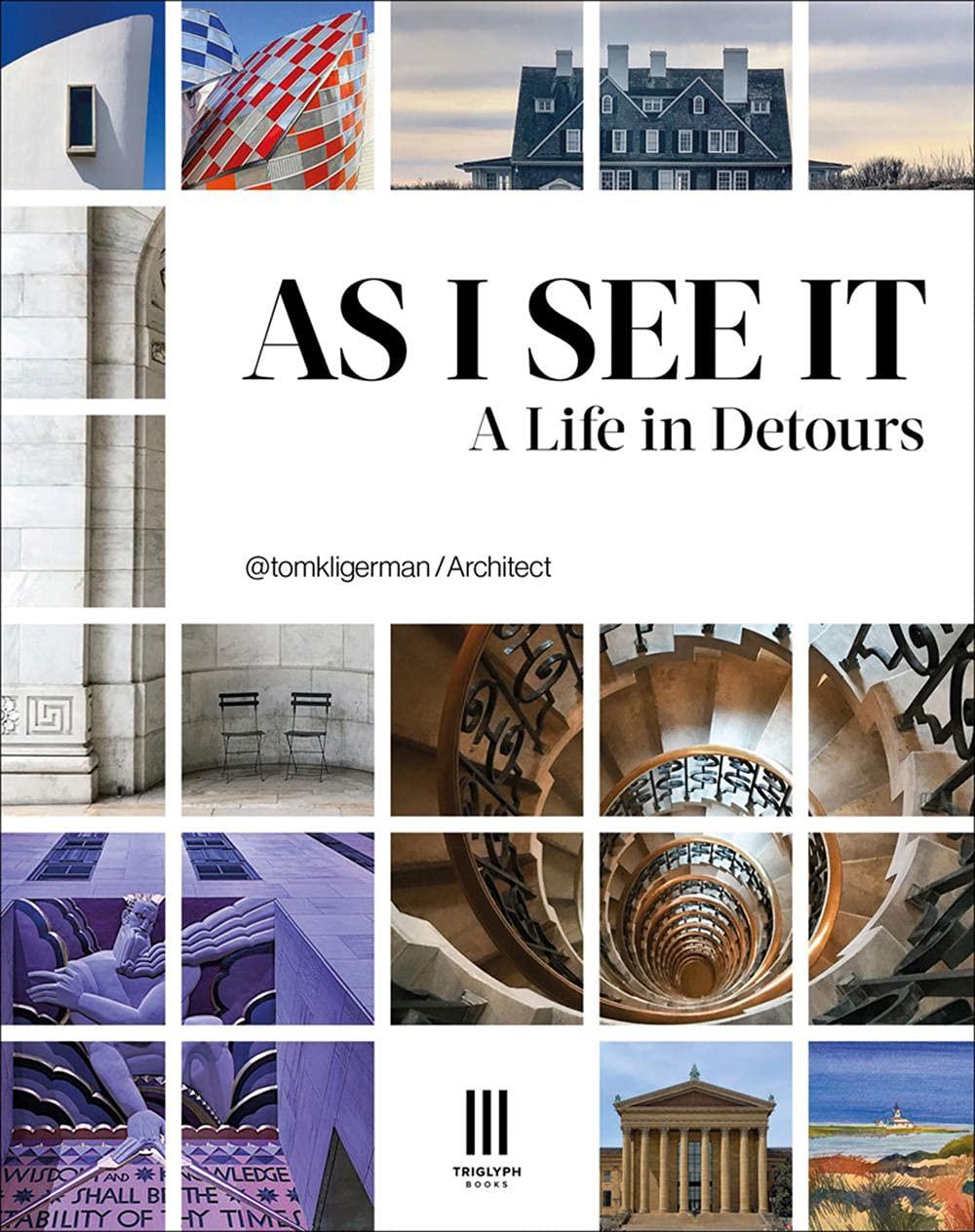

Thomas A. Kligerman, noted architect and partner at Ike Kligerman Barkley, created a completely new aesthetic experience with As I See It: A Life in Detours. The book—which started with a call from Triglyph Books in England—captures the unique duality between source and subject, featuring photos taken from Kligerman’s robust Instagram feed and anchored by personal essays that reflect on a life unconcerned with any digital medium. As a world traveler, Kligerman understands the impact of place, particularly in the face of a global pandemic. As I See It energizes its first-person perspective with storytelling and witty banter—and the adventurous addition of QR codes lead to unexpected places.

Here, the two authors meet for the first time to talk about what it’s like to cut new paths without really meaning to.

Alexandra, since you’re not in the design industry per se, tell us about your background and how this book developed.

Gargiulo: Aesthetically, I was always very interested in architecture and art, which led me to major in art history. One of the things I’ve always loved about L.A. is that it’s such a hodgepodge of architecture. I lived in the El Royale on [North Rossmore Avenue], which is a historic building. I just always thought it was interesting that some of these buildings in Hancock Park and Koreatown looked like a building you would see in Geneva or Paris—but the city’s not that old. I had a strong research background from law school and threw myself into the research of [these places]. The more I learned about the law of historical preservation, the more I got intrigued by the story and concept of some of these older buildings in L.A.

Tom, you were very clear in your introduction that travel is important to you. But this was COVID-inspired project, right?

Kligerman: I started Instagramming around 10 years ago, when my daughter showed me how to do it. I found it easy, and started posting a bunch. I remember thinking, Well, at some point it’ll become clear why Instagram is going to be important. As many magazines are disappearing, I realized that Instagram was sort of a replacement for [publication opportunities]. That’s one reason why I started doing it. Another is that I like taking pictures. I liked being part of a community of normal people who aren’t necessarily professional photographers but who take beautiful images. I find it fascinating. It’s like anything—you try to train your eye, but the more photographs you take, the more you begin to see opportunities. I like the instantaneous aspect; you take a picture and you post it.

[As for] the book specifically, I do love to travel. Every year, I go on a sabbatical for about a month. Nobody can find me except my assistant and my wife. I’ve lived in Rome, New Mexico, Mississippi. When COVID hit, I was in India on my sabbatical, and I had to run home and couldn’t travel. So I started thumbing through all my photos—it was like a little escape. I have 60,000 photographs on this phone now—it’s insane. And all of a sudden [Triglyph] called out of the blue and said, “Hey, you want to do a book on your Instagram?” So that’s how it happened—if they hadn’t called, [the project] never would have occurred to me.

Alexandra, had you ever put this kind of content out prior to your book?

Gargiulo: No. I’ve actually never connected much with Instagram, which is bizarre for my generation, but I’ve always really loved tangible things like books. So, everything I took was for the coffee table book.

Kligerman: It’s funny you mention that, Alex, because one of the things I tried to do in this teeny little book was blend [the traditional aspect of books] with the sort of blogosphere or [digital realm]. We have a library at my office with 6,000 books on design and architecture—soon to be 6,001 when I get yours. And I love the permanence, the smell, everything about them. And I thought it’d be kind of cool to add these QR codes sprinkled throughout, and each one takes you someplace unexpected. So I tried to blend the printed world with the [digital world].

I have a question for Alex. Is this your first book, and did you like doing it?

Gargiulo: Yes, and I did like doing it. There were so many different stages. At first, it was figuring out how to curate what I wanted to show versus just “all the buildings that Alexandra loves in Los Angeles.” And then it was taking the pictures, which I wanted to do on film because I thought that that matched the process of the way the buildings were built. The hardest part was that I had spoken with a pretty well-known publisher in the design space, but they wanted the book to be less about buildings and more about culture, [whereas] I always saw it as being more about the buildings and less about the culture. I thought, I can figure out how to do this myself.

Kligerman: That’s interesting. This is my third book. The other two are on the work we do at our office, and in both of those cases, we actually had an agent. I think you’re brave. I mean, I was the editor of my high school yearbook. That was my experience.

Gargiulo: So was I, actually.

Kligerman: Oh, really? Probably a different year for me. I loved it. Did you work with the graphic designer?

Gargiulo: I did—an editor and graphic designer.

Kligerman: Isn’t it an amazing thing when they show you the first pass at the layout? I think that’s one of the great things about writing a book—you have time to stop and think about things, but it’s also a time when you look at yourself through someone else’s eyes—a writer and a graphic designer. In this case, I did the writing. I think no matter what field you’re in, doing a book is an amazing exercise.

Gargiulo: Yes. Because there’s the creating it and the making it, and the making it involves all of these painstaking details that seem very far from the creating. And then there’s the selling it part.

Kligerman: That was the biggest surprise for me. No one tells you what a huge part that is. As important as it is to do this as a tool for self-reflection, at some point, you want your voice to be heard by others.

Thinking about the visuals and format, what size are your books?

Kligerman: I think it’s 5-1/2 by 7-1/2. You could put it in your purse; it’s very small.

Alexandra, yours is beautiful and oversized.

Gargiulo: It’s 10-by-13.

What was the thought process behind the size of these? You sit sort of in opposite corners.

Gargiulo: For me, I’ve always loved the big art design book. Also, the way that we shot the building influenced the size. Any historic building—before 1972 [or thereabouts]—that you’re taking photos of from street view isn’t subject to copyright. So, obviously, Tom, those are all your own images, but when you’re going and getting other people’s images, this could be a huge thing in terms of consent and cost.

So keeping that in mind, the photos we had taken were head-ons of the buildings, some of the signs, and then some of the little details that are pretty important in both art deco and revival styles. Having the photos on a bigger page allows the reader to see the whole building and then kind of zoom in on the details.

Kligerman: Yeah, mine was a little bit the opposite. I wanted to be in some ways like the experience of looking at Instagram. So these are bigger images than would be on your phone, but it’s still related, in a way. The pages are set up like Instagram, with a location at the top and a little caption at the bottom. I wanted it to be kind of a physical manifestation of Instagram. Also, I wanted it to be purchasable—it’s $17.95—something that you could pick up easily [and browse on your way to] checking out [while] buying a bunch of books.

Alexandra, did you take the photos yourself or work with a photographer?

Gargiulo: I worked with a photographer [Julian Burgueño] who specializes in taking photographs on film and works in fashion. We kind of took them together.

And how did you both approach the text? Because that’s minimal and distinct in both of your books.

Kligerman: The text is pretty much all new. We produced the whole thing in about 10 weeks, but I was thoughtful and did spend time thinking about my captions. The idea was to create a trip, a kind of voyage, a little escape book for people during COVID. You can look at it for a minute or for 15 minutes.

Alexandra, your book is not super text-heavy. Was that because you wanted this to be mostly a visual journey?

Gargiulo: Yes. In the first draft of the book, I had a lot more text. When I was originally working with the publisher, some of the positive feedback I took away was to have less text and let the images sink in and speak for the kind of the story I was trying to tell. I also included quotes. If you read all of the captions, the foreword and the quotes, you really have enough. I’m not the one to speak on every architectural aspect of these buildings, because that’s not my field, and there’s so much to say about that. I was trying to say something different than [focus on] every detail of the way the building was constructed.

The mood you both create is light—it isn’t this big, heavy philosophical thing.

Kligerman: It is light. Like Alex’s, [my book] is not meant to be any kind of definitive tome on architecture. It’s quick thoughts on different things—some are sort of humorous, some are serious, some are just an observation. I guess if you read the whole thing, you learn something about me—it is a little bit of an autobiography. It’s funny—we’re doing another book on the office, Alex, and it’s got an intro, a preface, an afterword and heavy captions.

We’re in a time when, unless you’re getting a degree or a historian or a serious reader, the world has changed—people don’t necessarily want to pick up a book and see all that text. I think it intimidates and puts some people off. We’ve just gotten used to things like Instagram or Facebook snips, or even blogs. I don’t know if that affected you, Alex.

Gargiulo: I completely agree. There’s a great coffee table book that really inspired me called Los Angeles Palms. And it’s very small, very thin—just pictures of 64 palm trees across L.A. I love a book that’s on a super niche subject. At the bottom, it has the cross streets where the palm trees are, and then in the back, it has one page about palm trees with two columns in Times New Roman. That’s it, and it’s great.

It strikes me that a lot of the world went into episodic viewing during the pandemic. How did you decide to pace and format your books?

Kligerman: It’s basically these pairs of pictures. But like a song, it needs a chorus as well as the verse. So then we then decided to have six or eight little autobiographical mini stories dispersed through the book and overlaid on the pairs of pictures. We tried to give them interesting titles—“Beetle Cats I Have Known,” “Two Queens and a Camera,” “The Good Old Humber.” Beyond that, [I included] some of the conversations I’ve had on Instagram as another overlay. So there are different elements to make it not too monotonous. It was almost like a building. There was a structure to it. We started off with the broad brush, then began to develop a little more and got into these sections. And dispersed are these QR codes that if people take the time to look at them, it kind of takes you into another pacing of a different kind.

Alexandra, how did the formatting and pacing change when you went from working with a publisher to doing this project yourself?

Gargiulo: There were some good things. The book is structured by chapters, and I use three neighborhoods. It was always going to be about Hancock Park, Koreatown and Miracle Mile, because kind of the focus on apartment houses in L.A. in the 1920s and 1930s. More apartments were built in L.A. in the ’20s than almost any other time because it was when the city was growing and people were moving here for the film industry. So I started with chapters, with chapter openers, then a montage [which offers] a preview, and then I take it building by building. In each chapter, we profile five or six buildings, and those kind of anchor the chapter, along with the quotes in between.

The quotes are so charming.

Kligerman: Are these quotes by famous people?

Gargiulo: Yes. The quotes by well-known people are there to set the backdrop. Because all of these revival buildings were built to make the city look old, including some of the signage with names like El Royale, St. Germaine … to try to make the city feel like Europe, which is super Los Angeles.

I think it brings context. A lot of people didn’t respect Los Angeles architects as much because everything had this fantasy and whimsical feel. So, the quotes kind of anchor that, you know—like William Faulkner lived in one of the buildings, so there is a quote from him about L.A. being a little ridiculous. There is Andy Warhol, who wrote about how L.A. is like plastic.

I think one of my favorite ones was Emily Mortimer.

Gargiulo: About how Los Angeles is a beauty parlor at the end of the universe.

Both of your books have departures in the pacing. Tom, you have the QR codes, and Alex, you include building permits.

Gargiulo: For every building, when I started my research, I pulled the original permits, which was pretty easy to do. The majority of these buildings have no preservation, no designation, no name—it was all very quick. That was the best way to find out the date, the architect, things like that.

And the price in some cases?

Gargiulo: Yes—how much they were going to pay for construction or things like that.

Alexandra, you had the opportunity to go back to a site to shoot it again or reflect on it, but Tom, you didn’t have that advantage because you captured these experiences in the moment.

Kligerman: Yes. They were taken all over the world. So I had photographs of Japan or Israel or Italy or wherever, and I couldn’t go back. There were some technical things I had to deal with. When you post on Instagram, it dumbs down the pixels, so you can’t take an image off of Instagram and print it in a book, because the resolution is much lower. So, there are pictures I wanted to put in the book, but all I could find is the image on my Instagram, so with those I’d have to redo them. Ironically, there was one photograph of a hotel in Century City that I had taken in 2010 and I wanted to juxtapose it to a stepwell in India. It’s funny—the one picture I did go back to reshoot was in Los Angeles.

Tom, your timeline for this book was fast. You said around 10 weeks?

Kligerman: Yeah, something like that. They wrote in February and we wanted it to come out for Christmas. So the schedule was really compressed.

Alexandra, how long did Preservation of Style take?

Gargiulo: The whole process was about three and a half years. I was laissez-faire about it for the first couple of years, and then I started to really focus on the making it part. It took me a while to figure out the logistics of printing it myself, and I wanted to print it with a really high-quality printer, which is the hardest part, to find someone that is familiar with books like this. And there were some global shipping delays and things like that.

Kligerman: Where was it printed?

Gargiulo: It was printed in China.

When you work with a publisher, you have the advantage of all the technical know-how and their handling. But to self-publish is to inherit all of that stuff. Was that a big learning curve?

Gargiulo: It was. I was lucky, I have a really great editor [at Te-Mata Studios] and she had done books before. She worked for Mario Testino for a long time, so she knew about the print file process, which can be very tedious and difficult.

Kligerman: Every time you do a book, yo learn something new. With the latest book I’m working on, I’ve learned about different kinds of paper: Italy has certain sizes; and it’s cheaper to print in China, but the shipping is much longer …. It’s like a three-dimensional puzzle.

What was the challenging part of the process? Were there any happy accidents?

Gargiulo: For me, it was the decision to self-publish. At first, I was really overwhelmed. Also, I had a four-month global shipping delay with COVID. There was a container shortage and then the ports were backed up. The printing and shipping took nine months, and the Long Beach Port was almost 90 days backed up to clear customs.

That ended up working out in my favor in releasing the book. Releasing a book in the fall, like the gift-guide season coming up, is much better than releasing a book in February, right after the gift-guide season ends. So I think from a PR and sales standpoint, it is better.

Tom, did you have any happy accidents?

Kligerman: As far as difficult parts, I thought this [process would be] a breeze. I thought, I’ve got all these pictures, I’ll just send them in. But it took a long time to assemble them—again, probably because I didn’t have high-res [versions]. Things are a lot more work—it’s like Thomas Edison, you know, 2 percent inspiration, 98 percent perspiration. So it was simply more work than I expected at a very busy time.

As far as happy accidents, I generally like meeting people, interviewing for jobs, getting the job. I like working with clients and builders. The happy thing for me has been the two book launches, one in New York and one in London, which were really fun. I I think there were about 90 people at the London opening. I didn’t know anybody, but it was in Robert Kime’s gallery in England, and everybody’s in coat and tie. It was so elegant. It was this beautiful fall evening. The people side of [the process] has been pretty fun, and working with everybody at Triglyph Books has been fantastic.

Any favorite responses or reactions?

Gargiulo: [It’s been really nice to] see how supported you are. We just did a book launch at Clare V., a [retail fashion] chain based in Silver Lake where we’re selling all the books. It’s really great to see when brands want the book, especially doing this myself and going the self-publishing route.

[My other favorite moment was capturing a] building in Hancock Park designed by an architect called Max Maltzman who did The Ravenswood. They ran out of money during the first year of the Depression in 1930, so the building, which was going to be his version of art deco and revival together, sat without a roof for five years. Then in the 1940s, the army bought it and made it an apartment building, [which was then] going to be torn down to build a big co-living space there. When someone who lived there told me that, capturing it in this book made me feel really good, like I had accomplished something in memorializing this building and its story that’s not going to exist anymore.

Kilgerman: Wow. [For me], it’s the reactions I have from people who are close friends and say really nice things. And then there are people who follow me on Instagram who write and say, “I just got two copies of your book and it’s incredible. How do I get it signed?” It’s a really nice feeling that people [saw] it and read it and took the time to write—even one nice sentence, or a photograph of the book on their dining table with the wrapper just taken off. So, it’s just a very nice feeling.

Homepage image: An estate featured in Tom A. Kligerman’s As I See It: A Life in Detours | Courtesy of Tom A. Kligerman