If you have disruption fatigue, know that you’re not alone. As digitally native companies have stormed the marketplace with a direct-to-consumer model, everything from mattresses to eyeglasses to olive oil has been disrupted. Even as you read this, there are scores of entrepreneurs in boardrooms pitching venture capitalists on a vision of cutting out middlemen and bringing high-quality goods to the masses at a friendly price.

Who can blame them? The global scale of the internet offers businesses a seductive reward: If you can make your product sing online, your total addressable market is ... Earth. That fact alone has powered much of the innovation of the past 10 years, as entrepreneurs have clamored to cut margins and leverage a planet-sized market to make a profit.

At least, that’s the theory. But as the online marketplace has gotten more and more crowded, two factors have put the squeeze on direct-to-consumer brands in the home world. The first is true of all companies doing business online: the rising cost of customer acquisition. “Google and Facebook are very expensive,” says Jonathan Bass, CEO and founder of D2C furniture brand Whom. “People don’t realize that being on the internet is as expensive as having a store on Fifth Avenue and 55th Street.”

The second is specific to home furnishings: purchasing frequency. While customer acquisition costs have followed a moon-shot trajectory, the average consumer doesn’t buy a sofa any more often than they did a decade ago. (By contrast, high-frequency products like makeup and razors are a perfect fit for D2C math.) As a result, digitally native companies in furniture and home goods have had to spend increasingly large sums of money to acquire a customer, who makes one purchase, then promptly disappears for six years. The math is brutal.

There is, however, a class of customer that purchases more than one sofa a year: interior designers. Many direct-to-consumer brands that launched with the intention of selling to a consumer audience of millions are now realizing the huge potential in reaching only a thousand people—as long as it’s the right thousand.

D2C Foundations

Roxy Te started her direct-to-consumer brand Society Social in 2011 with a light heart and a “let’s see how this goes” attitude. She had left behind the world of corporate fashion and returned home to North Carolina to help out with the family business, a wholesale furniture company with a manufacturing operation in the Philippines.

“I thought, Maybe I can create a brand or a retail arm that could be another avenue for sales,” she says. “I didn’t have formal training, but I have a factory that’s been making private-label furniture and decor for businesses for 30-something years. I took it seriously, but it was a side project.”

Then, as the fallout from the 2008 recession worsened, her parents’ company shrank and shrank. Te began to realize that rather than a side hustle, Society Social had become the main act. “I saw the business go from a ton of people to a skeleton of what it had been, and it was heartbreaking,” she says. “I realized I needed to grow as fast I could.”

Like many founders, Te launched her brand with herself as the first test audience. She was a design junkie, and had long lusted after the custom upholstered pieces that populated the pages of House Beautiful. A sofa in one of Tory Burch’s apartments served as a design lodestar; Te began crafting Society Social with a vibrant traditional aesthetic and customization options that were normally reserved for the trade. Tassels, yes. Trim, yes. Blazing hot pink upholstery? Also yes.

“I started the brand for that customer who wanted high design but couldn’t afford it—that was me!” says Te. “I had two upholstery pieces, and six bar carts—Mad Men was big. Every one of them could be finished in a custom color, and we had fabric options.”

Despite designer-friendly DNA, Te didn’t even think of the trade for the first seven years of her business. The reason is simple: the margin game.

FINE MARGINS

The gospel of the direct-to-consumer model is the elimination of markups that are traditionally baked into the cost of shipping, marketing, selling and retailing goods; those costs are slashed and the savings are passed on to the consumer, with the manufacturer pocketing a tiny profit on production. It’s how D2C brands are able to offer a luxury-ish product at an affordable-ish price (and why they are so focused on scale). It’s also the reason so many can’t simply sell products in stores and make money: Stores demand a markup that’s not baked into their business model.

So do designers. So for years, D2C brands like Society Social have balked at trade discounts. But as Te’s prices began to creep up from the absurdly low (in the early days, she charged less than $1,000 for a custom sofa) to the reasonable (prices for a similar piece now start around $1,500), the math began to change.

“As we adjusted the pricing structure and more people found out about us, we ran some numbers and I realized there was room for a margin,” says Te. In 2018, she settled on a 20 percent trade discount—enough to sweeten the deal for designers, but not so close to the bone that it threatened profitability. In the course of a year and a half, her trade business has grown 150 percent, and she’s made connections with high-end designers like Alexa Hampton.

A 20 percent discount is more or less the high-water mark for D2C brands. It occupies a sweet spot, significant enough for designers to make a small cut, but lower than a traditional retail markup of 50 percent (keystone is the industry term). Other brands, like The Inside, offer 10 percent. Splitting the difference, Denver-based furniture startup Sixpenny gives the trade 15 percent off.

Whatever the number, the basic mechanics of D2C businesses put a relatively hard limit on the trade margin they can offer—such companies generally can’t match the depth of discount offered by a local workroom. But in reaching out to the trade, they hope to offer the same thing they offer their civilian clients: speed, convenience and good quality at an affordable price.

As a result, generally speaking, the brands we spoke with weren’t hoping to compete with designers’ showstopping centerpieces. Instead, their goal was to become a trusted go-to for secondary items. In short, the play is: For the guest room, shop us instead of RH.

The high-value client

If some slightly more mature D2C companies have ended up backing into a designer audience, Bass is hoping to jump right in. The CEO of brand-spanking-new furniture brand Whom is making a concentrated effort to cater to the trade right out of the gate.

Bass’s company launched this summer with a high-volume marketing campaign featuring millennials partying on furniture (Bass: “The age of quiet, Leave It to Beaver marketing is over”). The company has since toned down the ads and is focusing more on conveying its sustainability practices and single-source production facility. But outwardly, much of Bass’s approach thus far has been about capturing attention in a crowded consumer market. Under the hood, though, he’s making a direct play for designer business.

“We felt from day one the design community was integral in making this work,” Bass tells BOH, a lesson he says he learned as the manufacturer of the Badgley Mischka Home collection. “Designers are in charge, and we want to make this an easy go-to for them.”

Whom offers a 20 percent discount to the trade and an extended selection of colors and customization options not available to consumer clients. And, at least for the time being, it’s giving designer clients a huge discount on shipping—a significant perk, since freight charges are often a massive “hidden” cost of furniture shopping.

Such efforts, Bass seemed to intimate, represent a paper-thin (or perhaps nonexistent) margin for Whom. However, he emphasized the importance of trade clients. For one, the potential lifetime value of a designer is far greater than that of the average customer. For another, getting big with designers has ancillary benefits.

“Our thought process was, as you build a designer base, you eliminate having to spend money for advertising,” he says. “If you look to RH, it became cool because the design community made it cool. And then the design community got screwed by them. The design community is savvy enough not to make the same mistake twice.”

Bass says 30 percent of his young company’s business is to designers, and that he’s receiving 40 or so trade program sign-ups per day. It’s too soon to say whether Whom can establish a permanent foothold in the trade. However, the mere fact that a direct-to-consumer CEO is strategizing around designers so intently is telling—competition in the space is heating up.

Custom made

One of the early qualities of direct-to-consumer businesses was a singular focus on one thing. The idea was that these companies would perfect a single item and attempt to completely own it—Casper for mattresses, Quip for toothbrushes. In recent years, the picture has gotten a little more complicated as companies have sought to extend their purview with new brand extensions, but it’s broadly true that D2C companies tend to be focused on getting a few things exactly right.

By contrast, D2C brands that want to win with designers have to be good at customization, and the ones that have made the most progress within the trade tend to have the capacity built into their DNA. But heavy customization presents its own challenges. It’s time consuming, and more difficult to scale. And capabilities that designers see as standard may confuse the general public.

Some brands are using digital tools to mitigate that risk. The Inside, for example, has a robust platform that helps shoppers understand customization options with visualization tools. Their play has been to replicate a simplified version of the workroom experience, but online, and straightforward enough that anyone use it.

Most small D2C brands haven’t invested as heavily in their tech platforms as The Inside. Ironically however, many of them offer a greater degree of customization—COM in particular is often a differentiating factor. Basically, the rule of thumb is: The more complex it gets, the harder it is to make it work smoothly online.

Society Social is shooting to occupy a happy middle ground. Te’s brand offers some custom capabilities—COM, choice of trims and tassels, custom colors for case goods and a wide range of fabrics—but stops short at specifying pieces down to the millimeter. Her website has some visualization tools, but assumes some level of customer savvy to envision the final product. As Te has changed the business to more consciously target designers, she’s made a happy realization: “Designers are the best customers. You don’t have to educate them, they get what all this stuff is for.” (She’s since developed a trade portal on Society Social’s website that allows designers to see their pricing clearly.)

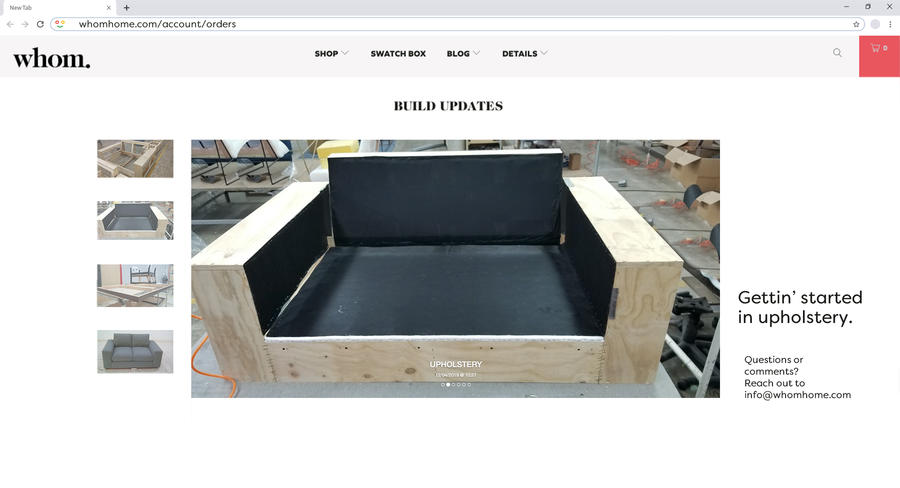

Bass too is shooting for a divide-and-conquer strategy: Customers who sign up for Whom’s trade program have access to a wider range of fabric options than the general public. A tool that allows customers to see photographs of their piece as it’s being built, he hopes, will allow Whom to compete for the attention of designers who don’t have time to schlep down to the workroom on the regular.

On the other end of the spectrum are brands like Roger + Chris. Founded in 2011 by TV veteran Roger Hazard and former tech exec Chris Stout-Hazard, the company has balanced an irreverent spirit (you can play Chesterfield Tetris on their website) with an ambitious goal: to essentially replicate the custom capabilities of a local workroom online, direct-to-consumer.

Roger + Chris offers a huge range of customization, not only fabrics and finishes but also heights and depths. Such capabilities make the brand a compelling option for designers (the founders estimate that at least 30 percent of their business is to the trade). However, their selling platform is the antithesis of The Inside’s: Rather than a system of menus and visualization tools, you’re emailing directly with staff to complete the order.

It’s a system that works well to handle the nuances of a highly customized order. It’s also not as easily scalable as a system of digital tools. Therein lies a paradox that all D2C brands who reach out to the trade have to contend with: Satisfying a massive audience of consumers and satisfying designers require different, sometimes mutually exclusive strategies. It’s tough to offer a full range of customization options and make it simple enough for anyone to understand and offer a trade margin and make a profit at scale.

For their part, Hazard and Stout-Hazard are happy with their corner of the market. “We’re not interested in doing everything in your home,” says Stout-Hazard. “We’re the right fit for some things—and when we’re right, we tend to be really right.”

Changing of the guard

If D2C brands are able to truly break through and claim a big slice of trade business, it will likely be due to a number of factors coming together—ranging from a declining workforce for local upholstery showrooms to greater competition among brands to technological innovation. However, the biggest force that may push designers to choose D2C brands is simply a generational shift.

Younger consumers are increasingly comfortable buying online, even for categories like sofas and mattresses—as are younger designers. Te has already seen a huge shift in the relatively short life of her business. “It was definitely a challenge getting everyone on board when we first started, to get them to understand this is what the market needed,” she says. “When I said, ‘I want to sell sofas online’—you should have seen the look on their faces.”

Bass is more or less banking on it. “Millennial designers are more accustomed to shopping online, that’s obvious,” he says. “Older designers might not be buying online as much, but they might have an assistant who is. So our question was, Who do we want to identify and communicate with? Our thought was to reach out to the younger designer, to communicate with them. … Digital brands that can do what workrooms can do, only online, and really offer value and convenience to designers—those are the ones that will win out.”

Homepage photo: Courtesy of Society Social