Arthur Elrod designed homes for Walt Disney and Lucille Ball. Milo Baughman made his furniture. James Bond fought henchwomen in his living room. Yet the interior designer who defined Palm Springs modernism in the 1950s and ’60s has largely faded into obscurity. Now, journalist Adele Cygelman resurrects Elrod’s work in a compelling new book, Arthur Elrod: Desert Modern Design (Gibbs Smith).

“People have been so interested in the architecture and furniture of the period for so long that it’s sucked up all the energy in the conversation,” Cygelman tells Business of Home. “I think people are starting to get tired of that, and more interested in the interior designers.”

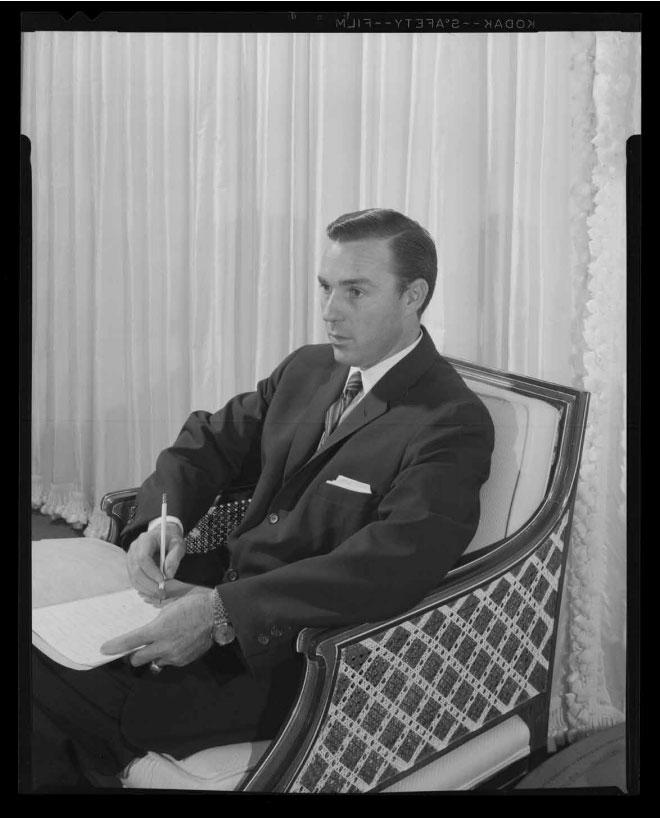

Cygelman’s book, as much a biography as a monograph, presents a thorough portrait of the decorator as a young man. Born in 1924 in South Carolina, Elrod was a farm boy, but he didn’t stay one for long. After attending Clemson, he made his way to the West Coast and never looked back. In Los Angeles, he studied interior design and took elocution lessons to lose his drawl. His early projects fit the prevailing Southern California style of the era: a moody version of Spanish colonial dominated by browns, beiges and heavy heirloom furniture.

After moving to San Francisco in 1952, Elrod began to chart his own course. He was commissioned to create a museum installation for General Electric to celebrate the 75th anniversary of the light bulb, and the experience was a revelation. His “Celestial Room,” a mock “nighttime” penthouse, demonstrated advanced lighting equipment and ignited a lifelong fascination with new technology. From this experience, Elrod learned the importance of carefully controlling all aspects of a room, from the furniture to the lighting, for maximum effect.

It was in Palm Springs, however, that Elrod found his muse. He opened up shop in the desert village in 1954, and his small firm was an immediate hit. Just as Elsie de Wolfe cleared out the cobwebs of Victorian style half a century earlier, Elrod began sweeping aside the trappings of Spanish colonial. The furniture got lighter and sleeker. The rooms got airier. And most importantly, Elrod brought a new palette—emerald greens, swimming pool blues, canary yellows—to the desert. “He had a saturated palette unmatched by anyone except maybe David Hicks,” says Cygelman. “Elrod was working like the color field painters of the era, but in 3-D.”

The designer’s interest in new materials and technology placed him firmly in step with the Southern California architects of the 1950s and ’60s, who were pushing the envelope of modernism. Especially in the desert, spacious, open-plan ranch houses enclosed in glass were fast replacing adobe bungalows. Elrod enjoyed fruitful partnerships with the architects he worked with, and no matter the style, his homes tended to feature sophisticated stereos and lighting systems.

Elrod was ahead of his time in another crucial respect: self-promotion and media savvy. In advance of his move to Palm Springs, he took out a series of illustrated ads in local papers that boasted the furniture brands he sold exclusively and established a charming aesthetic for the firm. More importantly, the ads led to editorial coverage in the papers, where Elrod remained a fixture for decades.

And long before hordes of online influencers began pursuing strategic relationships and sponsored content, Elrod made the most of his handful of celebrity clients. A pair of homes he designed for Ball and Desi Arnaz led to extensive press coverage and a branded ad for Bigelow carpets that the meticulous Cygelman unearthed (“Only the best would do for Mr. and Mrs. Arnaz’s dream home”).

Elrod went on to design homes for the likes of musician Hoagy Carmichael and Disney, but the designer’s most famous project was for himself. In 1968, he collaborated with architect John Lautner on an atomic-age fantasia in Palm Springs, now known as the Elrod House. The home—with its iconic circular glass-enclosed living room, concrete UFO roof and incorporated boulders—is a sleek modernist triumph, with a drop of camp. It endures to this day, partially due to a prominent scene in the James Bond film Diamonds Are Forever.

The house was also notable for a less splashy reason: Elrod incorporated a pair of eventual continental classics—Pierre Paulin’s ribbon chair and Gaetano Pesce’s Up chair—into the design long before they became staples. Cygelman anecdotally credits him with bringing European furniture to the desert.

At the tragically young age of 49, Elrod died in a car crash that also claimed the life of a design associate, William Raiser. His most iconic interiors were mostly removed in renovations throughout the following decades and his reputation began to fade away. Cygelman attributes his disappearance partially to the ephemeral nature of an interior designer’s work. However, she thinks Palm Springs might have had something to do with it: “He was out in the desert,” she says. “He was published, but people weren’t paying him the same attention they were to designers in New York and L.A.”

Even in Palm Springs today, Elrod is mostly only remembered in connection to the iconic house that bears his name. His love of vibrant colors, however, has endured. “The design world can be so monochromatic and afraid of color,” says Cygelman. “But not in Palm Springs.”