Hospitality design has finally dumped the outdated and overplayed conventions of yore: ugly curtains, boring carpets and tired furnishings. The hottest hotels, restaurants and shops are getting the residential treatment and grabbing all the Insta-attention. But how easy is the leap from homefront to concierge desk?

The way we dine, how we choose to relax and where we shop reflect contemporary cultural desires. The past decade in experiential consumption has seen a rather striking transformation—and behind it is an elite group of interior designers who specialize in reconceptualizing public spaces into increasingly unique, luxurious and unexpected venues. Hotel and restaurant chains no longer adhere to a monolithic, one-size-fits-all approach to interiors, and instead seek out interior designers who can choreograph the nimble dance of coalescing a sense of brand identity, place and a unique visual experience for clients.

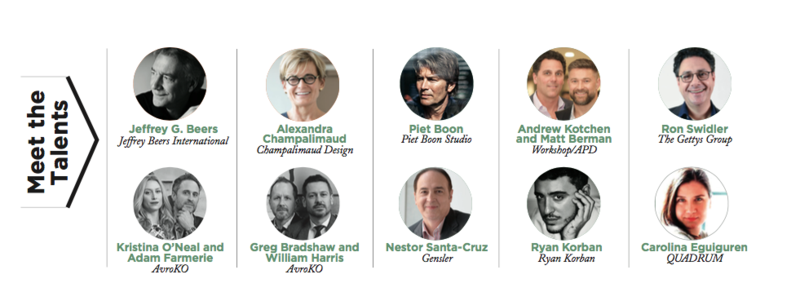

Across the board, designers say residential and commercial are increasingly informing one another. “There’s been a strong desire from travelers and hotel folks who seek out hotels for a more intimate experience—a home away from home—and less of a sterile environment,” says architect Jeffrey G. Beers. Conversely, he says, time in high-end hotels influences what guests want to come home to in their own residences. “People are more well-and internationally-traveled and have seen some of the best properties around the world. They want great living experiences at home that are more hospitality-driven,” says Beers. Interior designer Alexandra Champalimaud echoes that thought, “People who travel a lot these days are enchanted and influenced by what they see—the details are done with great rigor and precision and thought.” “You could say,” adds Matt Berman of New York-based architecture and design firm Workshop/APD, “hospitality is re-creating luxury homes and vice versa. It’s an interesting conversation, and exciting to see how they both speak to one another.”

BOH subscribers and BOH Insiders.