Small-batch everything is having a moment. It’s happening in food, fashion—and home furnishings. Artisans in four places where craft is flourishing today share what it means to commit to making things the old-fashioned way.

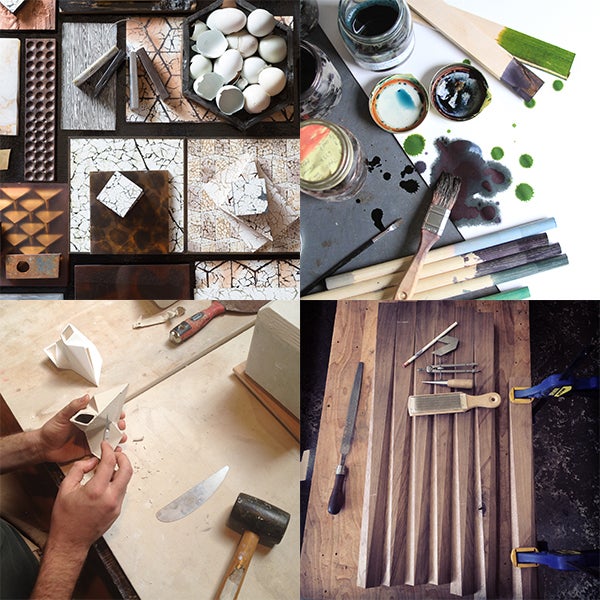

There is an undeniable romance to objects with an origin story. From the curve of a hand-hewn wooden chair and the gravitas of a wheel-thrown bowl to the allure of a one-of-a-kind marbled wallcovering, the magic of artisan-made items is in how they effortlessly elevate the everyday. And while mass-produced product seems to dominate the conversation these days, makers of all stripes are experiencing a renaissance of sorts within pockets of the country where artisan innovation is quietly thriving.

“People who appreciate craftsmanship are interested in collecting future heirlooms, not just picking something out of a catalog,” says interior designer Brad Ford. He should know. He is the founder of two initiatives dedicated to contemporary makers: Field + Supply, an annual high-end craft fair in the Hudson Valley, and FAIR, a New York Design Center showroom that represents makers across the country, like California furniture designer Chuck Moffit and the furniture and lighting design studio Workstead, based in Brooklyn and Charleston, South Carolina.

“Clients from coast to coast are beginning to appreciate not just the talent, but also the narrative and nuance of these designers and the materials they use,” says Ford. But the burgeoning demand for all things handmade doesn’t make producing laborious, time-intensive pieces of furniture and textiles an easy feat—or a simple way to earn a living. Success is predicated on balancing various, often conflicting, factors like an inspiring environment, ample materials, a place to showcase work, and support from a like-minded community. As the real estate mantra goes, “location, location, location” can make all the difference. We asked artisans working in four hotbeds of American craftsmanship about their life’s work and the realities, good and bad, of their creative communities.

BOH subscribers and BOH Insiders.