Sprawling, net-zero spaces leverage creative new technologies and methodologies—proof, once and for all, that sustainability comes in all sizes.

In recent years, sustainable living has been practically synonymous with small spaces—micro-apartments are lauded and Marie Kondo has made it trendy to live with less. It’s a correlation that’s simple and easy to understand: A smaller building footprint means a smaller carbon footprint. So it follows that large homes, especially newly constructed ones, can be frowned upon by green enthusiasts as wasteful energy hogs that are bad for the environment. But it doesn’t have to be that way.

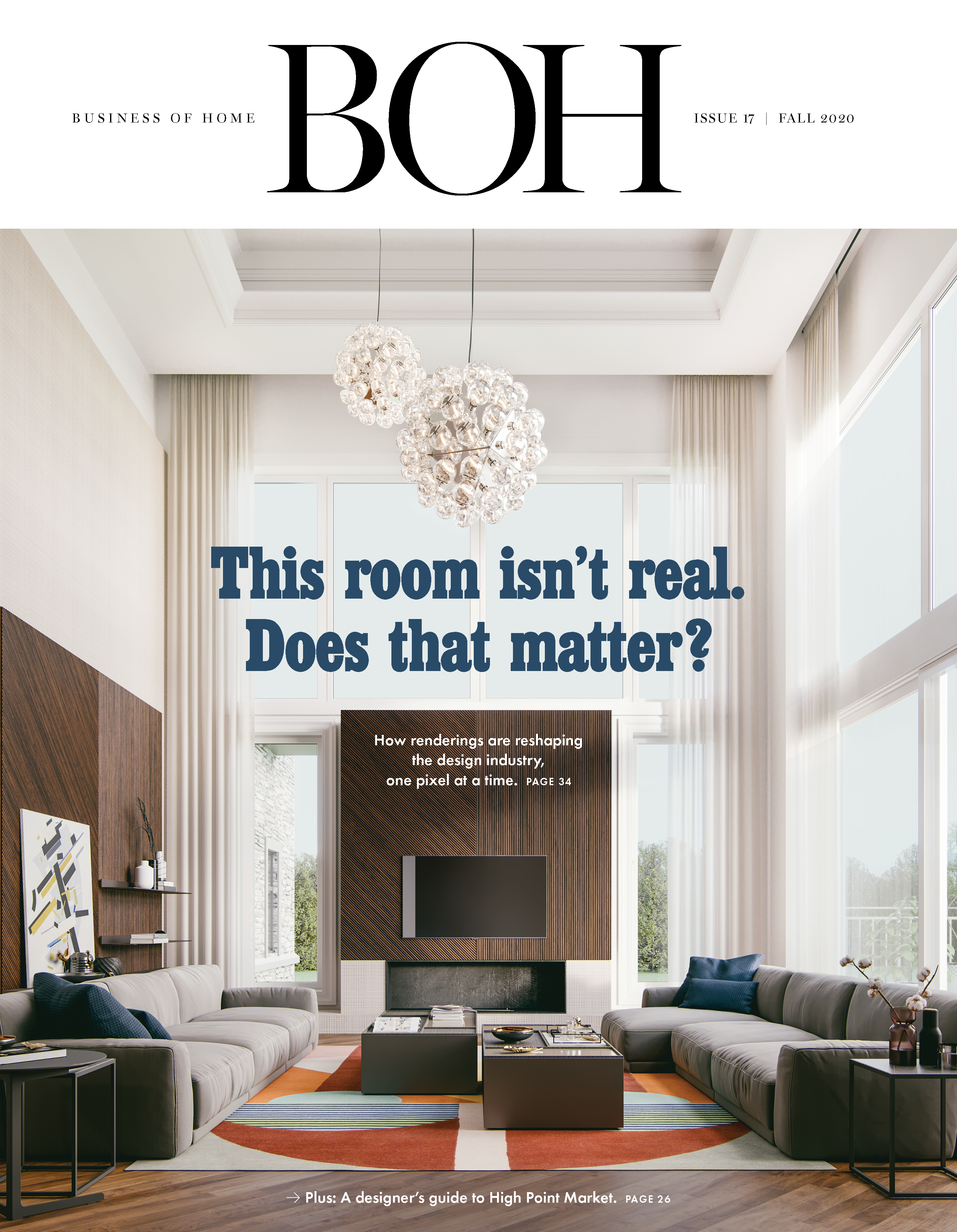

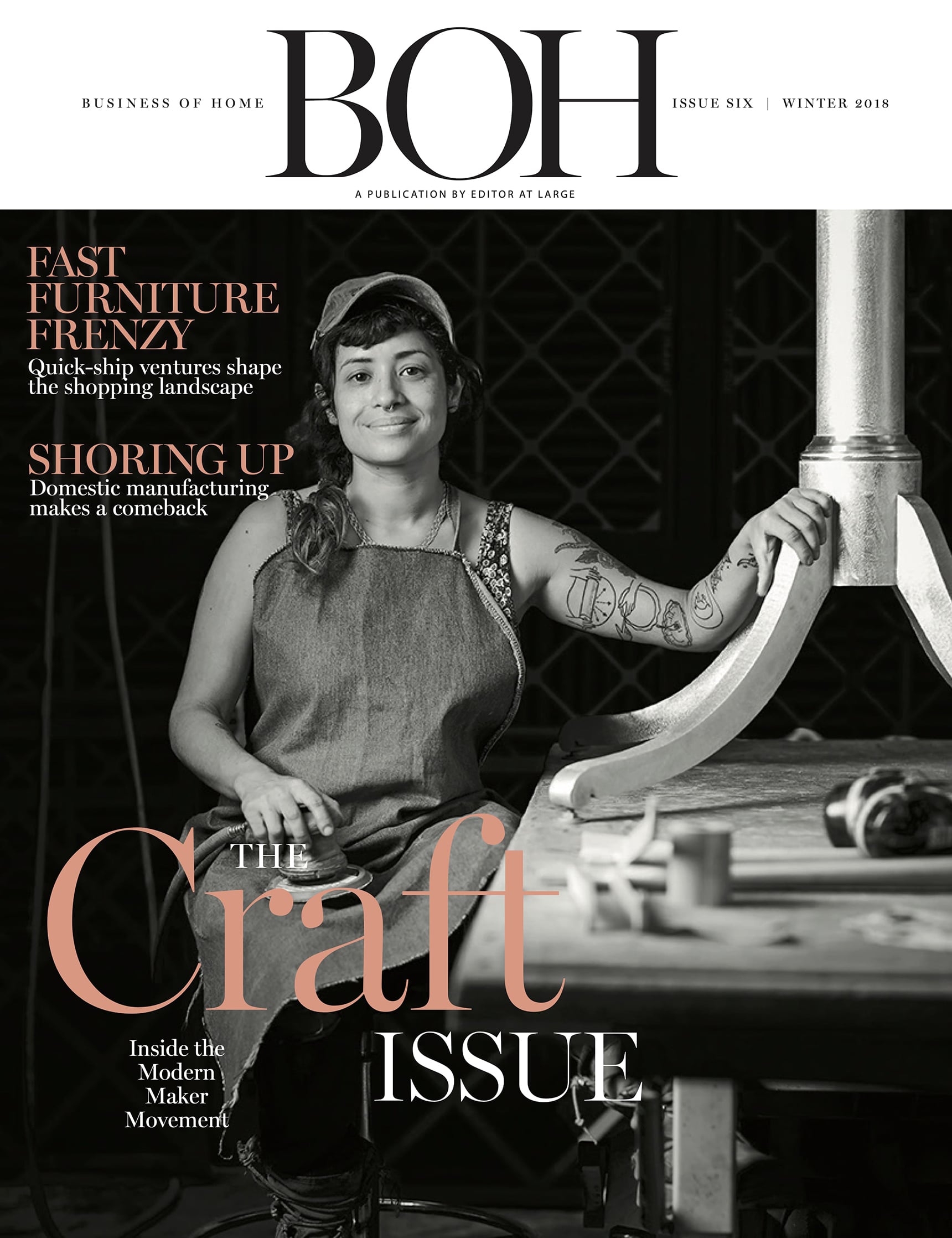

The homeowners drive Teslas, so the firm installed two electric vehicle charging stations in the garage.Matthew Millman

Ready to dig in?

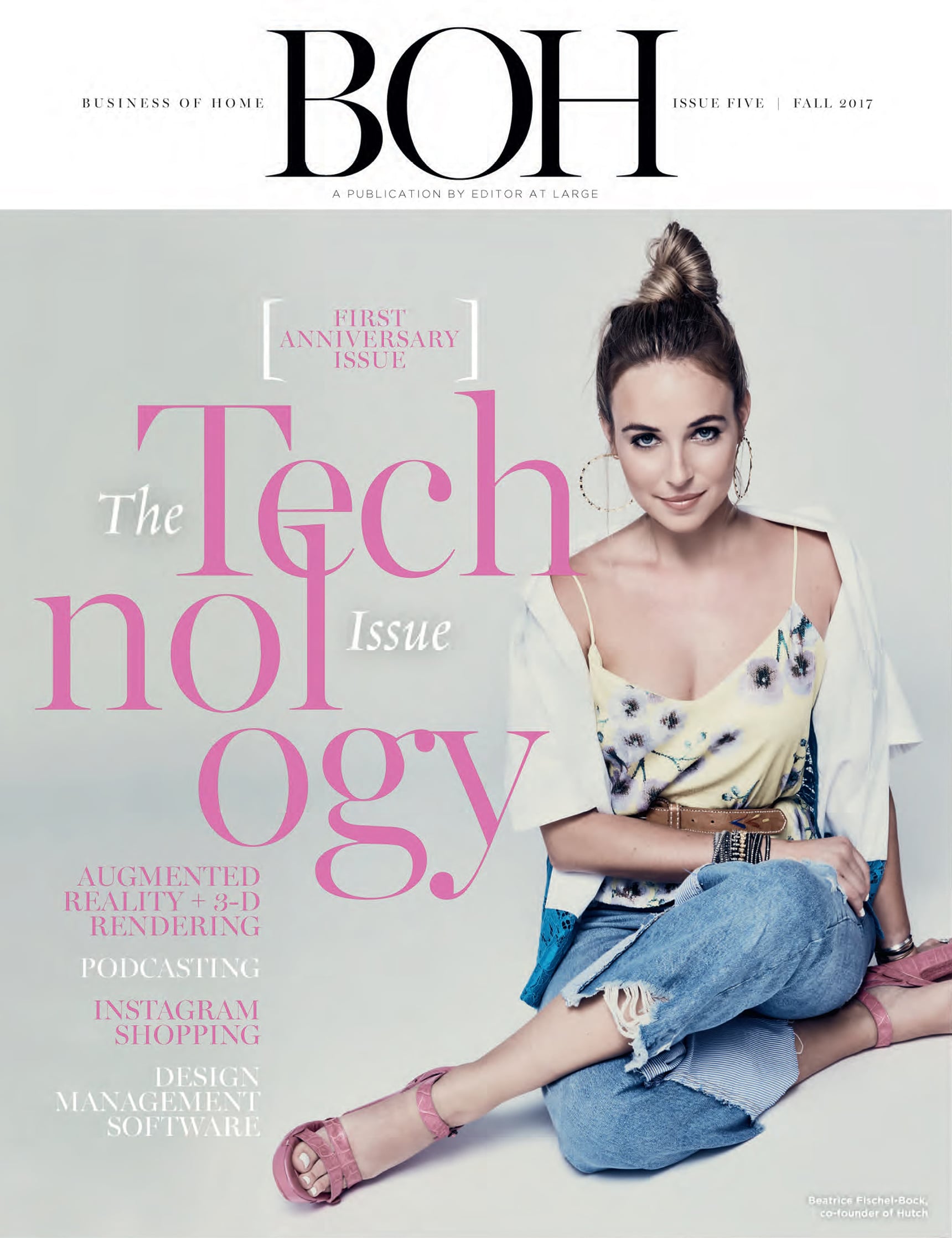

This article is available exclusively for

BOH subscribers and BOH Insiders.

BOH subscribers and BOH Insiders.

Want full access?