In the world of traditional design media, it’s business as usual. A celebrity—Diplo, in a tank top—is on the cover of Architectural Digest, and just in time for summer, outdoor-furniture roundups can be found at every turn. But lurking below the surface lies a shadow media where the vibes are different. There, Polly Pocket is a small-space pioneer, the color palette of contemporary decor is suffering from “poo-ification,” and overhead lighting is a metaphor for the male brain. Welcome to design Substack.

For the uninitiated, Substack is a platform for publishing email newsletters. Launched in 2017 by two entrepreneurs and a former journalist, it’s pretty low tech as disruptive technology goes. The innovative touch was mainly a clever bundling of features—including, crucially, a payment tool—that allowed anyone to start a newsletter, get subscribers and (hypothetically) make money.

Early on, Substack lit up with political commentators, poets and entrepreneurship gurus. Over time, it became a home for fashion writers, lifestyle influencers, chefs, DIYers, gardeners and a woman trying to learn 12 languages in 12 months—name a topic, there’s a newsletter for it. But, possibly because ours is a visual industry—or maybe a tech-averse one—interior design was slow to get in on the craze. (The feeling may be mutual: Substack has only a general “design” category that lumps in shelter content with graphic and industrial design.)

Over the past year or so, it has felt like the tide is turning. A handful of design writers have launched buzzy newsletters that are gathering steam, while designers themselves are starting to experiment with the format. Interior design on Substack feels less like a ghost town and more like a frontier village, welcoming newcomers by the day.

FREE FOR ALL

Substack attracts unique voices, at least partially because of its business model. Traditional design publications make money through a complicated mix of advertising, subscriptions, affiliate revenue and newsstand sales, creating a web of incentives that can flatten what ends up getting published. (In a nutshell: If it’s not going to go viral, pop on a magazine rack, spike affiliate sales, or highlight an advertiser, why do it?) Newsletter writers, by contrast, mostly make money when someone finds them interesting enough to pay for access to what they have to say. Consequently, people on Substack tend to say interesting things.

“I realized I was in the habit of buying design magazines, but I would never read them. The writing in a lot of circumstances was just descriptions of images—it didn’t really reflect the conversations about interiors and decor that I was having,” says David Michon, a longtime design editor and the author behind buzzy Substack For Scale. “Even some of the writers of those very articles I wasn’t reading—you would meet them at a party and they’re sarcastic, critical, observant people. The writing they were asked to produce was not really as good as the conversations we were having. … Like a lot of personal projects, [For Scale] came out of a desire to produce the thing I felt was missing.”

For Scale is Substack par excellence: a vital, joyfully weird publication that absolutely could not exist within the context of traditional design publishing. Tackling everything from the pretension of discourse at Milan Design Week to Williams-Sonoma CEO Laura Alber’s pronouncements on AI, Michon explores the design world in a tone that shifts—sometimes within the same sentence—between academic, mock-academic, earnest and snarky. Buzzwords rendered ironically in all caps are common.

The newsletter is, at first glance, a little obtuse, which does nothing to hurt its cache: Michon has amassed almost 8,000 subscribers and has become a savvy name-drop among the design world’s cognoscenti.

The most engaged-with posts, he says, are “in the category of things that a lot of people are thinking but no one is saying”—like, for example, the tendency for design to be polarized toward either quiet luxury browns or explosive color. A representative excerpt: “The world of SOCIAL MEDIA loves two things: poo brown, because it looks soothing to whizz past in a scroll; and, the arresting vibrancy of hyper-pop rainbows. The former is supposed to be SOPHISTICATED, the latter is supposed to be “UNIQUE” or personality-driven. Both are, in fact, now generic.”

But, Michon adds, one of the joys of the publication is slipping out of the zeitgeist and writing about things that are willfully off-trend. “I just started drafting a story about the Tolomeo lamp. There’s no news about it. There’s no anniversary. It would be impossible to pitch this story to a design magazine. That’s what’s so fun and thrilling about [writing a newsletter]—it can just be: ‘You know what? This week I’m interested in the Tolomeo.’”

Substack-as-sandbox was part of the draw for Leonora Epstein, former editor in chief of Hunker and author of a Substack called Schmatta. “I was realizing that I had a lot of things to say that didn’t fit into the way web publishing works, where you’re chasing virality or an SEO hit,” she says. “There are not a lot of publications that would say yes to 1,300 words where I talk about Edith Wharton’s influence on rich people and how it connects to Succession.”

Schmatta isn’t quite as out there as For Scale. Epstein shares shopping guides and indulges in the time-honored design-media tradition of inventing trends (her slightly tongue-in-cheek contribution to the genre: Grotto Girly, a look that’s “giving grifter, scammer, naïf,” and is characterized by “texture, beach, shell-shine oblivion tinged with ethereal indifference”). But the publication is far more personal, idiosyncratic and, frankly, hilarious than the usual fare—would Elle Decor, for example, run an article with the headline “This AI decorating tool turned my daughter into a giant butt plug”?

“For me, Schmatta is a way to reframe the narrative around design to be more casual, humorous and grounded in reality,” says Epstein. “I feel like I’m channeling a voice that’s breaking the fourth wall between editor and reader in a way that wouldn’t work at a publication with multiple editors and contributors. … Even though it’s on a miniscule level [compared to consumer publishing], I’m able to see engagement. Every time I post, there are new subscribers, people are talking to me, designers and editors are reacting, and it does confirm to me that there is something to trying to discuss decor in a way that’s not so traditional.”

Lily Sullivan’s Love and Other Rugs is a case in point. Sullivan, a former style editor at Domino, left shelter publishing behind to do a stint at sexual wellness startup Maude—she often describes herself as a “retired vibrator salesman”—but found herself missing the home world. When she started kicking around the idea of writing a book, a newsletter emerged first. Two years later, it has almost 3,000 subscribers.

Sullivan’s Substack is difficult to define. A mashup of dating memoir, design blog and shopping guide, Love and Other Rugs takes well-trod media genres and Frankensteins them into something charmingly new. One edition starts with a double entendre (“one night stand or two?”), recounts dates both good and bad, muses on grief, and ends with a quick five-point shopping guide for side tables.

“I don’t want to say I’m the only person that could have written this, but I had so much experience in home, and so much experience in understanding relationships, sex and intimate care—those two things were very much at the forefront of my brain,” says Sullivan. “It started as a little bit of an on-the-nose joke, like, ‘Can we compare men to furniture?’ But the comparisons kept writing themselves. I’m working on one now about windows and naked neighbors, but also about exposure and what it’s like to document yourself on the internet, and I’m also sharing the best window treatments. They all somehow fit together.”

Not every shelter Substack is a genre experiment—some are just thoughtful musings on design. Former Curbed editor in chief Kelsey Keith’s Ground Condition is a reliably sharp take; Business of Home sustainability columnist Laura Fenton writes a newsletter on small spaces; and a bevvy of former British design journalists write about everything from renovating old houses to “shopping, dogs, hens, LIFE.” You don’t need a hyperniche concept to succeed, but eyeballs on the platform do tend to coalesce around strong voices, unique perspectives, confessions and hot takes.

“A lot of Substackers feel like we’re writing for ourselves, and that’s the most exciting thing. The audience is responding to the fact that it’s not controlled by anyone else—we’re not on a seasonal calendar or tied to trends,” says Sullivan. “It’s wholly our own.”

PLATFORM FATIGUE

Some start a Substack to get outside the confines of traditional media. Others come to escape the algorithm. While Instagram is still the de facto town square of the industry, you don’t have to look too hard to find designers who have come to find the platform completely exhausting, or at the very least robbed of much of its early joy. What was once a place to share and discover has become, for many, a frantic marketing exercise. For now, newsletters offer the promise of a more thoughtful alternative.

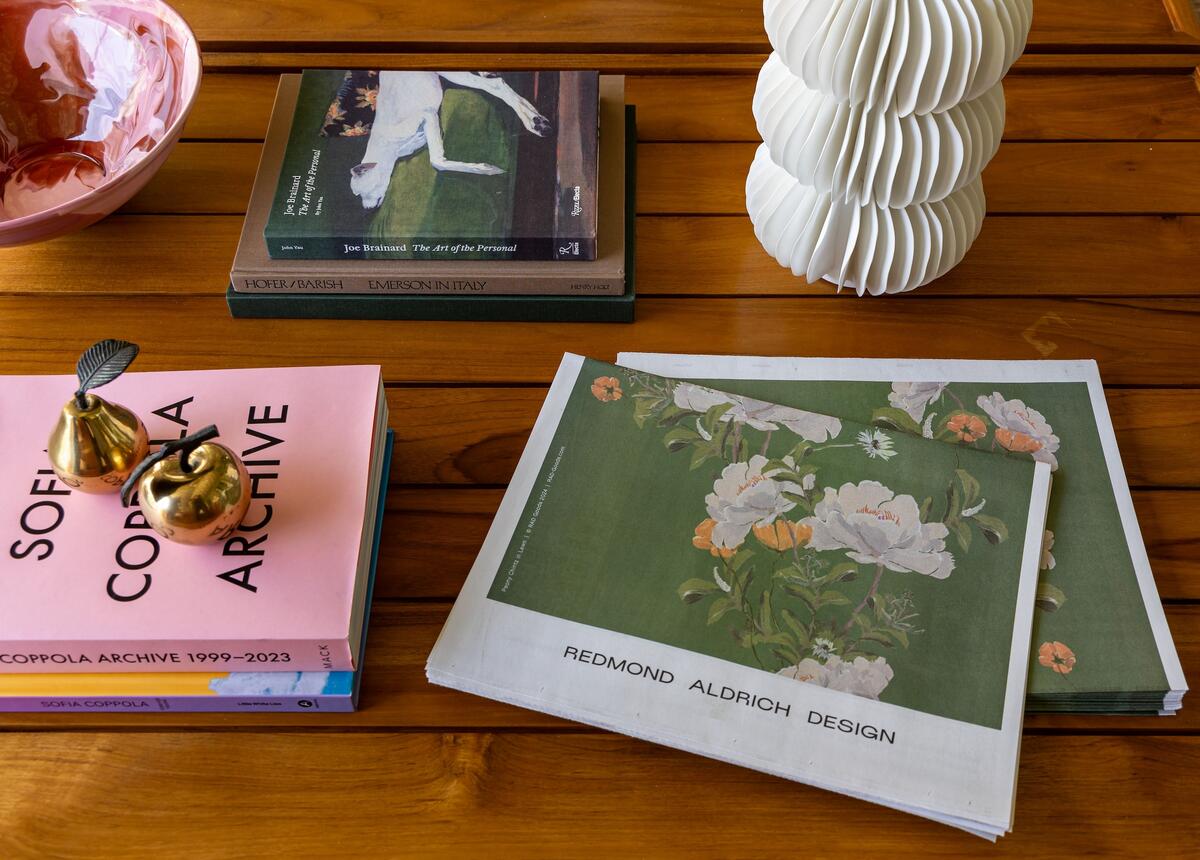

“There’s a lot of fatigue with Instagram. It’s a very low effort-to-reward ratio,” says Chloe Warner of Oakland, California–based firm Redmond Aldrich Design. “If I’m honest, I don’t even like it that much; it’s more that I’m addicted to it. I feel gross every time I put the phone down—it’s like, what was I even doing there?”

Warner arrived at Substack after following a variety of writers on the platform. Last year she decided to start a newsletter of her own that would chronicle the experience of running her firm, her thoughts on design and, as she jokes in her inaugural letter, “fun and sleazy things like listicles.”

The result was RAD Minimag, a mix of inspirational content, design analysis and cheerful-but-real insight on running a growing business—Warner’s post about creating her room at this year’s Kips Bay Decorator Show House in Palm Beach is among the more entertaining accounts of the showhouse roller coaster. The letter has grown to more than 1,000 subscribers, but Warner says the main reward is the depth of connection, not the breadth of reach.

“I’ve gotten really lovely in-real-life feedback—people call me about it, my husband’s friends read it. My book club clapped for me, and I was like, what? No one has ever complimented me on an Instagram post,” she says. “There’s a lot of connecting with people; it’s very tangible and real.”

Paris-based author, stylist and entrepreneur Ajiri Aki also came to Substack partially to get away from another platform—in this case, email marketing service Mailchimp. Aki had already done the difficult work of building up an audience, but found herself frustrated that the platform continued to raise prices. Why should she pay for a service, she reasoned, when she could migrate over to Substack and get paid instead?

Aki’s account, Notes on Joie, covers a wide range of subject matter, from musings on relationships to travel tips to the most recent finds for her e-commerce shop, Madame de la Maison. Like many newsletter writers, she has experimented with offering some content for free, while putting up a paywall for others. The results, she says, have been encouraging. “People really do want to support you,” she explains. “I have a founder tier, and part of the reward was that I would send napkins. But people would sign up, I’d reach out to them, and they’d never follow up on the reward—they’d just write ‘I love your work, I want to support it,’ which is really nice.”

Like Warner, a frustration with the constantly shifting Instagram algorithm has pushed her to double down on her newsletter. “I feel like Instagram is asking us all to do a chicken dance for free—forcing us to turn into videographers and making crazy reels,” she says. “Mailchimp was screwing me, Instagram won’t show my work unless I do their dance, and I was like—it’s time to get into Substack.”

RETURN ON INVESTMENT

The big question: Can you actually make money through Substack? In what will no doubt be a familiar refrain for platform hoppers of the past decade, the answer is: Yes, but don’t get too excited.

The economics of Substack are simple. Users can give their letter away for free, charge subscribers for access to certain content, or put the whole thing behind a paywall—the platform takes a 10 percent cut and adds a credit card transaction fee. Prices are entirely at the writer’s discretion, though most give away some aspects of their letter and charge between $6 and $15 per month for a paid tier.

There are those who make six- and seven-figure incomes through their newsletters (interestingly, one of the most popular, House Inhabit, is by a former home and lifestyle blogger who now writes about culture and politics). However, like many social platforms, Substack is more of a winner-takes-all tournament than a thriving middle class. The vast majority of newsletters will struggle to amass a significant subscriber base—that’s especially true in a category like design, where audiences have been conditioned to get content for free.

That’s not to say there’s no money to be made. Michon’s For Scale has around 500 paid subscribers, while Epstein says Schmatta’s base is growing steadily. Aki says getting a regular income stream from her newsletter has, at the very least, offered a reward that other social platforms haven’t delivered in recent years. “When you make a certain amount of money on Substack, it totally changes your attitude about Instagram and how much time to put into it,” she says, “When I’m making a couple thousand a month on the newsletter, I could care less about [Instagram] posts. The incentive changes everything.”

Substackers are also experimenting with other ways to monetize. Sullivan, for example, made a deal with DTC paint brand Backdrop to sponsor her first round of letters. The next volume, which launched in March, is backed by resale platform Kaiyo. Then there’s merch (For Scale has hats), events, and expansion to other formats—Sullivan, Michon and Warner have all published print editions of their letters.

However, for the most part, the Substackers reached by BOH treated their newsletter as something a little more than a side hustle, but a little less than a full-time job. Content creators see it as one piece of a larger puzzle that includes brand and book deals. Editors see it as a way to experiment, make connections and ultimately land more lucrative freelance work. Few and far between are those paying the mortgage with Substack revenue, and designers may find it even harder to justify the time sink. When asked if she hoped to get clients from RAD Minimag, Warner’s answer was simple: “No.”

What’s more, the platform isn’t exactly easy. Substack doesn’t require its users to pen 3,000-word ruminations on toile, and there’s a growing genre of those who mostly just curate inspirational imagery—but putting together a Substack letter is still more involved than throwing up a TikTok about Quiet Luxury. In a recent edition, Warner (half) joked: “You made it to the end! I’m thrilled! This took me approximately 300x longer than an Instagram post.”

But for all the challenges, there are undeniable rewards. In a rapidly shifting media landscape where print is niche, social platforms are all trying to out-TikTok TikTok, and Google is constantly tweaking its algorithm, there’s power in developing a direct connection to an audience through email. Long after all content becomes AI-generated interpretive dances, people will still open their inboxes.

Even if Substack doesn’t pay off in dollars, devotees tend to find the process of writing a newsletter far more enriching than churning out engagement-chasing social posts. Ours is a visual industry, and for some designers, writing may be more of a chore than a joy. But taking time to reflect on your business, your process—even your favorite side tables—can provide a benefit that goes beyond social clout or revenue.

“There’s a therapeutic aspect to writing and trying to compose something with words out of your work, even if it was experiential or visual,” says Warner. “Being able to put things in perspective and reframe things that were complicated and challenging at the time—that’s been huge, and I didn’t expect it at all.”