A collection of figurines displayed in an exhibit during Milan Design Week is drawing backlash online. The antique glass figures, which include stereotyped caricatures of Black, Asian, Middle-Eastern and Indigenous people, were shown in an installation by Italian architect Massimo Adario as part of a larger collective show, Campo Base, featuring the work of six architecture studios. On Saturday, the pieces were removed from the exhibit after the event’s organizers began receiving complaints; yesterday, images of the figurines began to circulate on Instagram in a post titled “Racism is not a design motif,” which was collectively authored by designer Stephen Burks, curators Wava Carpenter and Anna Carnick of Anava Projects and publicist Jenny Nguyen of Hello Human.

“We were deeply offended to see racist glass figures at the #CampoBase show, which depicted Black, Asian, Middle Eastern and Indigenous people as sub-human, reinforcing demeaning and racist stereotypes,” read the post, which has been liked more than 1,200 times. “Our first question is how could something like this happen at Milan Design Week in 2023?”

The seven figurines date from the late 1920s and are the product of a Murano factory called I.V.A.M. In an email exchange with Business of Home, Adario wrote that "the artistic language is the same for all the figures, including the one that would appear to indicate the Caucasian ethnicity, since this figure is made in transparent/whitish glass. For this reason, it’s my opinion that there was no intent to caricature only one, or some, particular ethnic group, but probably all groups." Adario wrote that he had recently inquired the set and included it in the exhibit because the figurines related “volumetrically and chromatically” to contemporary sculptures elsewhere in the exhibit.

“I was aware that exhibiting the glass figures was risky, but had not imagined they’d be offensive. I had hoped that their juxtaposition with the contemporary pieces—in terms of content, language, and ‘aesthetics’—would have started a different kind of conversation,” wrote Adario. “Clearly, I failed miserably in conveying my original intentions. … These figures—whether taken as [a] whole or as single pieces—are indeed offensive to a broad range of people, and I regret having caused hurt and provoked anger.”

In an interview with Dezeen, Burks drew a connection between the figurines and a disturbing thread of design history. “We must acknowledge that the historical objects on display in the exhibition originated from violence,” he said. “We must understand how their creation in the 1920s was derived from an unequal system of cultural exploitation borrowing directly from European colonial practices of dehumanizing ‘othering.’”

Federica Sala, the curator of the Campo Base show, apologized in a statement. “We regret what happened and we apologize for the discomfort this has caused. It was by no means intentional to offend anyone and we don’t want to minimize this,” she wrote. “It is our intent to listen and learn from this experience as our objective was not to create division or conflict. … We hope to open a path that leads to discussion, clarification and a better understanding of cultural, historical and social relevance.”

In their post, Nguyen, Burks and Carnick also critiqued the media and design influencers who recommended the Campo Base show, and for being sluggish to draw attention to the figurines. “How can it be that the media and design influencers have portrayed this show as a ‘must see’?” read the post. “And how have the racist figures not shown up or been condemned on social media until now?”

Many of the articles about the exhibition had been written based on press images that had not clearly depicted the figurines. In a note added to its original write-up of the show, Sight Unseen apologized for “sending anyone to the installation who may have been triggered.”

“Unfortunately, we posted this story before seeing the space in person, and we were unaware of the vintage glass sculptures depicting racist motifs that were included in one of the installations,” the update read. “We will be leaving the rest of the post up with this note in order to facilitate conversation and transparency about these persisting issues in design.”

Nguyen is hopeful that a positive dialogue can emerge from the controversy around the incident. “We wanted to create a conversation about how the industry, and each role within the industry can work together to not only stop this from happening again, but also to eradicate racism and look at ways we can level the playing field for BIPOC folks,” she told BOH. “Stephen, Anna and I talked at length about this show over lunch in Milan and realized that the only way we can combat this is through communication, dialogue and education.”

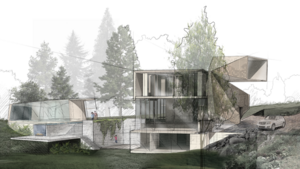

Homepage image: Massimo Adario’s Campo Base installation | Courtesy of Fuorisalone