Architect Peter Pennoyer is as much a part of New York’s design landscape as the buildings he works on, from The Metropolitan Opera Club and the NYSE Luncheon Club to the Moynihan Train Hall clock in the newly restored Penn Station. He has always been a steward of classic architecture, and today he’s taking it a step further as his firm launches a new Conservation division headed by architectural conservation director Lewis Gleason, which will specialize in the technical aspects of historic restorations and renovations.

Historic projects are by no means new for Pennoyer, given that he’s harbored a passion for old buildings since he was a child. For decades, his firm has taken on projects that require architectural conservation expertise—specialist knowledge about zoning and tax laws, liaising with New York’s Landmarks Preservation Commission, material life cycles, historical construction techniques and, importantly, how and where those techniques tend to fail. But like most architecture firms handling historic projects, Pennoyer has, until now, hired third-party preservation firms, bridging new and old through a series of planning meetings and communication.

As far as Pennoyer and Gleason are aware, Peter Pennoyer Architects (PPA) is the first major American architecture firm to launch a dedicated, in-house conservation team—a move that promises to increase operational efficiency, whether surveying a building’s physical evolution or filing LPC permits. “It becomes a six-week versus six-month process,” says Gleason. PPA Conservation currently has a dedicated team of three, and while they build out the division, additional staff members and designers with preexisting conservation expertise are helping to lighten the load.

For work requiring a conservation specialist (about a third of the firm’s projects), PPA has its in-house team to grease the wheels in an area that’s notoriously cumbersome and loaded with red tape. Grassroots organizations and local stakeholders often have a sense of ownership over historic sites, whether a building or a monument, often bringing strong emotions and opinions into the negotiations. Then there’s the government to deal with—certain building classifications demand further bureaucratic hurdle-jumping. And that doesn’t even begin to cover the feats of engineering, building and logistics required to execute the actual architecture plans if they’re approved.

“The questions that always come up are: How do we get this material? How do we replicate this detail? This facade was built 150 years ago; how are we going to make this work?” says Pennoyer. “Ninety percent of the masons in the city won’t know what to do. We need a [specialist] stonecutter; we need a cast-iron manufacturer that might be out of Alabama or Utah.”

Materially and stylistically, a good rule of thumb in historical buildings is “like for like”—shorthand for replacing a broken-down component with the same material and profile that was there in the first place, or as close to it as possible. That can be an expensive undertaking when it involves cracked marble stairs or a rusted cast-iron railing. It’s the work of conservation experts to communicate to the client that while the nominal cost of the material may be higher than a mainstream substitute, the real thing comes with the greatest longevity, allowing it to remain for another hundred years or so and usher in a new era of architectural history.

Beyond the historical value and design cachet that comes with restoring old buildings, there’s also a strong sustainability angle. As Gleason points out, the greenest building you can build is the one that’s already built. And as Pennoyer adds, “People are interested in the responsible use of our resources, and a very clear direction is to work with something that’s already in the ground, where the stone and steel is there—not to turn that all into landfill.”

In envisioning the future of New York’s architectural gems, Pennoyer and Gleason take ample inspiration from other cities that build a bridge between old and new with beauty, grace and functionality. “New York is always looking to increase density,” says Gleason. “But I think we can show that there’s a way to move forward without completely giving up what we’ve built in the past. In cities like Milan, London, Paris, they have to find ways to contextually add and preserve, but in New York, it often feels like one or the other. I realize PPA is just one small piece of that, but I think we will be able to demonstrate that you can have it both ways.”

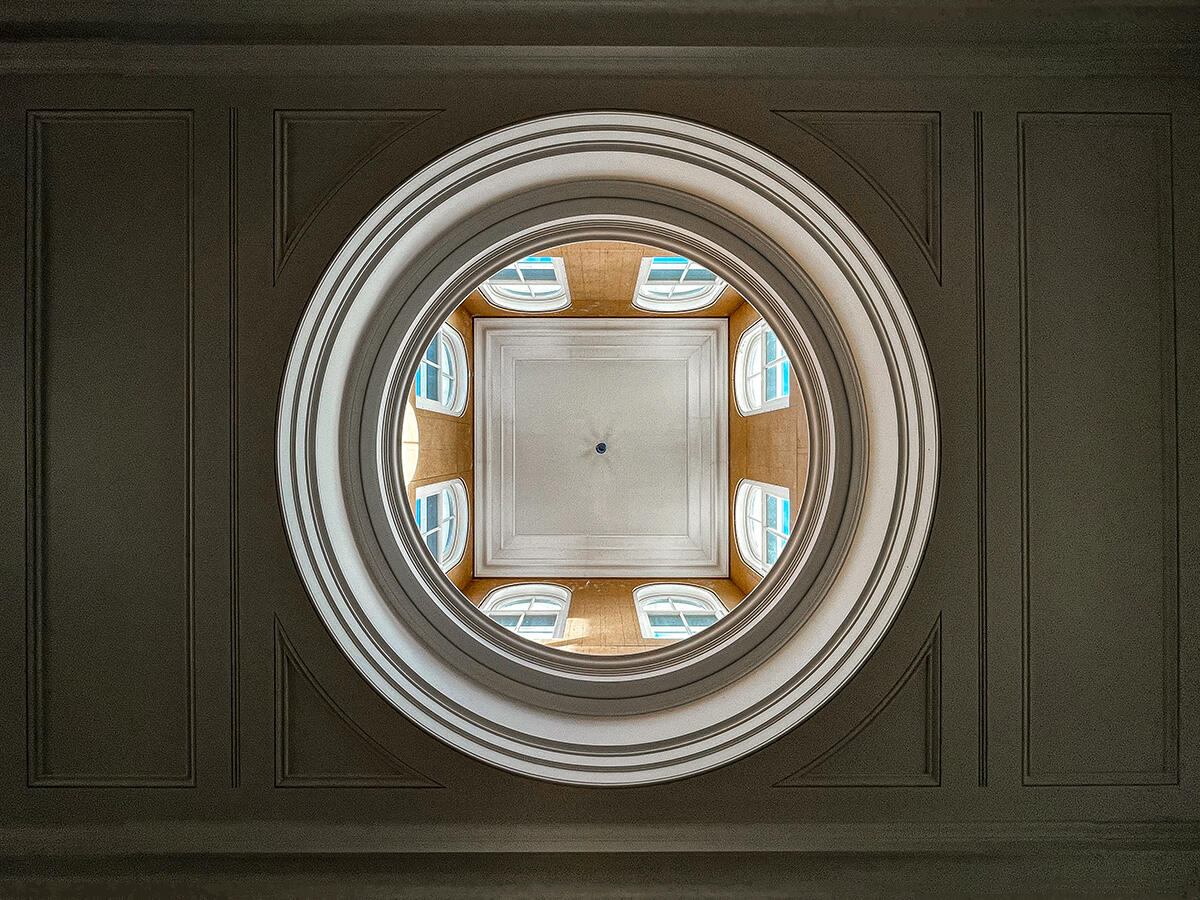

Homepage image: One of PPA Conservation’s current projects sees the team reimaging this Victorian home | Courtesy of PPA Conservation