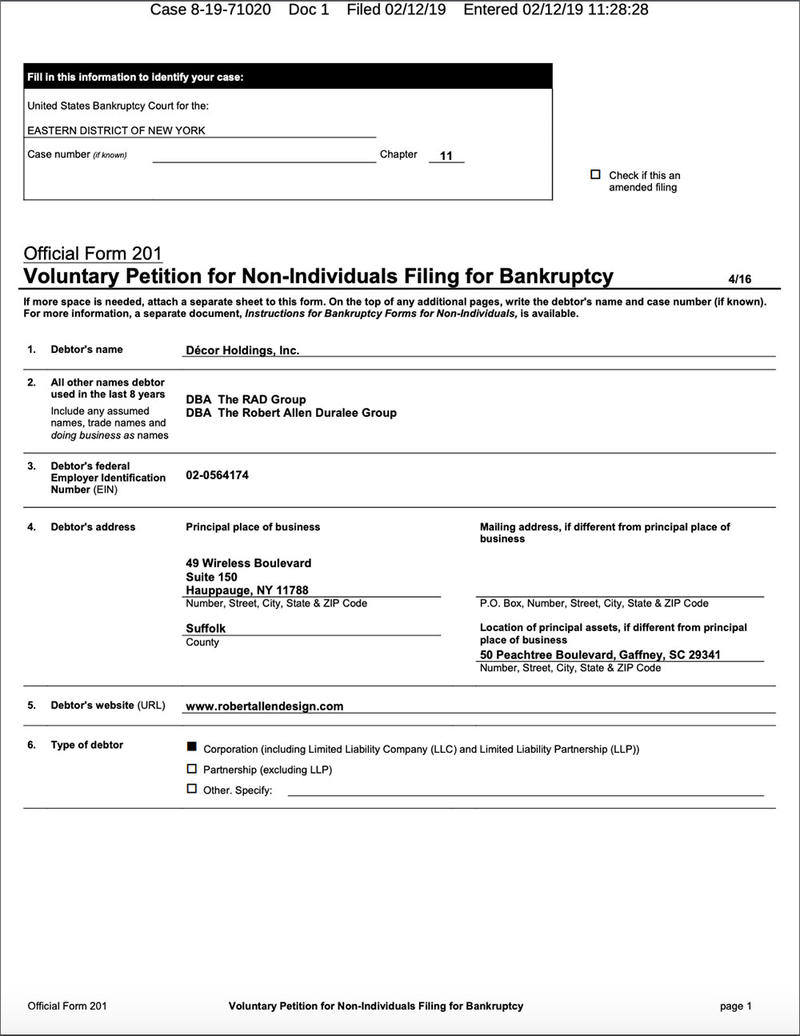

Earlier this week, Business of Home broke the story that fabric giant Robert Allen Duralee Group was filing for Chapter 11 bankruptcy. The development sent shock waves through the industry, leaving many wondering how to take the news and what to expect next. We took a deep dive into the bankruptcy filings and spoke to industry experts to get some clarity on the RAD Group’s prospects and the ripple effects on designers, creditors and the industry at large.

How did this happen?

In a word: debt. When Robert Allen and Duralee merged in 2017, both companies were carrying significant obligations. In joining forces, the pair hoped to streamline operations and form one profitable entity. Early outward signs were positive, and the new company’s leadership made changes that led to annual savings of roughly $10 to $12 million. Internally, however, RAD Group soon began to hit bumps in the road.

Bankruptcy filings reveal the newly formed company had difficulties uniting its two separate computer systems in order to cut down on operating costs. A more significant burden: duplicate showrooms. In many trade centers, both Robert Allen and Duralee maintained separate locations. When the companies merged, they found themselves unable to break long-term leases, forcing them to pay rent and staffing costs for two spaces when they only needed one.

Cash flow became a problem, suppliers weren’t paid, orders were delayed, and contractual disputes began to pile up. By February, the writing was on the wall.

Cash flow became a problem, suppliers weren’t paid, orders were delayed, and contractual disputes began to pile up. By February, the writing was on the wall.

A softening market was the final straw. The company reported a 14 percent decline in sales in both 2017 and 2018, and weathered several aggressive rounds of layoffs and cost-cutting measures—most recently in December 2018 and again in January 2019—but it wasn’t enough. Cash flow became a problem, suppliers weren’t paid, orders were delayed and contractual disputes began to pile up. By February, the writing was on the wall.

“It’s all about the debt,” David Klaristenfeld, vice president of Tulsa, Oklahoma–based textile company Fabricut and a former bankruptcy lawyer, tells Business of Home. “The debt was already high, and it gets close to unmanageable so that no matter what you do, you’re always playing catch up. Then you hit a hiccup in the market and it’s devastating.”

For Crans Baldwin, fabric industry veteran and founder of Darien, Connecticut–based consultancy Crans Baldwin & Associates, the bankruptcy calls to mind an experience he had working with textile designer Jack Lenor Larsen on a possible buyout of fabric house Kroll. At the time, both companies were struggling. After leaving a meeting with Kroll executives, Larsen dryly informed Baldwin that the merger was off: “Crans, I don’t think that two stale loaves of bread will make a fresh one.”

What happens next?

By filing for Chapter 11 bankruptcy, RAD Group can shed some of its debt and get out of its punishing long-term leases. (The filings indicate that they will likely terminate leases in 11 design centers by the end of the month.) The company has also secured a line of credit that will allow it to continue operating while it looks for a buyer. In a letter to employees, CEO Lee Silberman announced that he requested a hearing on the sale for the week of April 22. By then, Silberman writes, “We should know the results of our sales efforts.” In the meantime, Timothy Boates of RAS Management Advisors has been appointed to oversee the restructuring and sale. The company has also established a website for creditors and a hotline for customers with questions: 888-204-0582.

Will RAD Group be bought?

The company has said it is “aggressively pursuing multiple prospects” and working with “parties who have expressed an interest in purchasing Robert Allen Duralee”—strongly hinting that a buyer is already at the table. It may be hype, but it’s not an uncommon practice for distressed companies to court potential buyers before undergoing Chapter 11. RAD Group may well have already lined up what’s known as a “stalking horse” bid, the first mover in a bankruptcy sale. (In a recent example, Century parent company Rock House Farm acquired the three former Heritage Home Group brands, Hickory Chair, Maitland Smith and Pearson last fall.)

Stalking horse or no, Klaristenfeld is optimistic that RAD Group has a good chance to find a buyer. “[CEO] Lee Silberman is very smart, and I’m confident he’ll find a great partner,” he says. As for who might be interested in purchasing the fabric house: “It could be an international company looking for a foothold in the states, or another company in the states that has the same client but not the same product.”

What happens in the long term?

If the RAD Group is unable to find a buyer, the company will be forced to liquidate its assets to pay back the underwriting bank and its primary creditors. Staff will likely be let go en masse, locations will shut down, and inventory will be sold off at fire sale prices.

If the RAD Group is able to find a buyer, the company will likely go through a restructuring period to accommodate a partnership with its new owners. What that would look like is difficult to predict. However, freed from debts and burdensome leases, the company will almost certainly adopt a lean strategy.

Is the bankruptcy an isolated incident, or the canary in the coalmine?

Is the bankruptcy an isolated incident, or the canary in the coalmine?

What does the bankruptcy mean for interior designers?

In an email to customers, RAD Group asserted that it intends to “continue to operate its business as usual with anticipated improvements in service levels.” Though the email was accompanied by a mile-long legal disclaimer, there’s reason to believe that designers can expect normal service from the company—for the time being. “Now that they’re in bankruptcy and are funded, they’re granted a breath of fresh air to operate and generate some cash,” says Klaristenfeld. “They have the ability to buy themselves some time.”

What does the bankruptcy mean for the design industry?

The bankruptcy will have an immediate ripple effect on RAD Group’s partners. In its filings, the company indicated that it owed between $50 and $100 million to roughly 6,000 unsecured creditors and that no funds were available to pay them back. Though many of the biggest creditors (including Valdese Weavers, Sumec Textiles and Triplex Enterprises) are large conglomerates and can likely absorb the losses without going under, it will surely affect their ability to do business with other partners. Smaller companies may feel the pain more acutely.

Taking a broader perspective, the question remains: Is the bankruptcy an isolated incident, or the canary in the coalmine? It depends on who you ask.

“I don’t think this bankruptcy is a sign of where things are going,” says Klaristenfeld. “There are so few people who want to do what we’re doing. Even with DIYers, there’s still a tremendous design clientele. And it’s not an easy thing to stock 60,000 fabrics. For companies like us that have the inventory without a heavy debt load, we’ll survive the market and come out stronger.”

“I don’t think this bankruptcy is a sign of where things are going,” says David Klaristenfeld. “There are so few people who want to do what we’re doing.”

“I don’t think this bankruptcy is a sign of where things are going,” says David Klaristenfeld. “There are so few people who want to do what we’re doing.”

Baldwin takes RAD Group’s struggles as a warning against financially driven adventurism in the design industry: “Our industry is not, ‘If we invest X we’re going go get Y’ in the way you might think with a commodity product like soybeans.” He hopes that the decline of the RAD Group will have a positive outcome: a renewed focus on creativity among fabric designers. “Our industry has always succeeded when we took creative risks, not risks with investment banking opportunities. It would be great if what came out of this was everyone went back to their studios and said: ‘Let’s try something else.’”