Back in 2016, Los Angeles–based designer Jonathan Olivares was working on a piece of furniture specially for the Philip Johnson Thesis House at 9 Ash Street in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Built in 1942, the home, now owned by Harvard University Graduate School of Design, was a precursor to Johnson’s Glass House. In the end, Olivares developed a daybed made entirely out of woven textiles, which made its debut at Milan Design Week last week.

The original thesis house included a Ludwig Mies van der Rohe Barcelona Daybed, and Olivares, according to Danish textile brand Kvadrat, his collaborator on the project, “wanted to echo this for the space with a contemporary approach to the daybed.” He went on the hunt for an upholstery-grade textile to pair with a carbon fiber twill weave textile. The result? The Twill Weave Daybed and the Twill Weave textile.

Olivares had previously collaborated with Kvadrat for its Hallingdal 65 installation during Salone del Mobile in 2012, as well as on projects with brands including Nike, Knoll and Vitra. Of their latest partnership, he says, “The construction of this textile was informed by the twill weave and color of carbon fiber cloth. Carbon fiber is used in the construction of lightweight and strong components within the automotive, sailing and sporting industries. The development of a sister textile in wool allows designers to pair the rigid or flexible components of carbon fiber with a soft, upholstered component, resulting in a total object made entirely from twill weave cloth.”

The daybed itself is entirely composed of the fabric. As the brand notes, it is “constructed with a traditional twill binding, the textile’s full-bodied, magnified structure of diagonal lines [and] uses voluminous woolen yarns, making it akin to carbon fiber. This first textile was dyed to the same color as carbon fiber.”

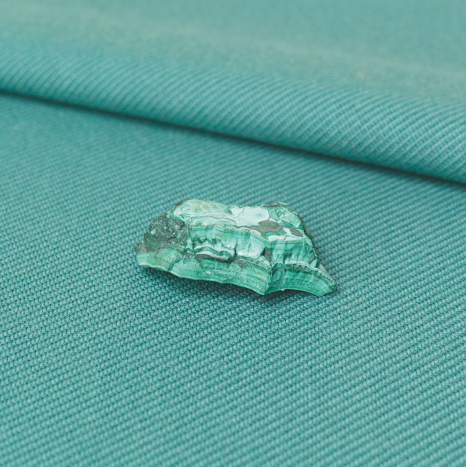

Olivares’s dye influences are drawn from raw natural sources. “With so much human and industrial meddling in the colors available to us, I became interested in peeling back the layers of intervention,” he shares. “This led me to visit the Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies at the Harvard Art Museums to study the minerals that were used as pigments before the advent of synthetic colors. Looking at the rocks and minerals—azurite, chromite, cinnabar, clay hematite, copper, galena, gold, graphite, green earth, gypsum rosette, Indian lake, indigo, lead white, malachite, Pozzuoli earth, realgar, willemite—I was viewing raw, unprocessed color. These colors stand for the earth, for a humbler interaction with it, and for less human intervention with natural phenomena. These are colors I can get behind.”

All the pigments used within the collection hailed from the Forbes Pigment Collection, which is part of the Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies, and, according to Narayan Khandekar, the center’s director and senior conservation scientist, “largely put together during the career of the Fogg Museum’s second director, Edward Waldo Forbes, director from 1909 to 1944. Forbes revolutionized the profession of museology in many ways at the Fogg Museum—which he considered a laboratory for art—and in doing so, laid the foundation of conservation and technical art history as scientific disciplines which continue today.”

“Part of this work was to accumulate pigments and their raw sources so that he would have reference standards in order to identify materials used by artists in making a work of art,” continued Khandekar. “Understanding the decisions an artist makes is as close to a conversation we can have when the artist is no longer alive, and the pigment collection is a way to ensure that this conversation is accurate. The collection has been shared with institutions in the U.S. and around the world, and continues to grow. At present, there are approximately 2,500 samples, and the pigments are still being used for their original purpose. The use that Jonathan has chosen is a first for this collection, and is something that would have been unforeseen by Forbes.”