One of the many ironies of the coronavirus era is the degree to which it has turned the established order on its head. Over the past two months, factories that normally churn out thousands of pieces a day have been shuttered, while tiny artisan workshops have kept humming along. Makers are outpacing manufacturers. The strangeness of the moment isn't lost on design writer Alisa Carroll.

“Some larger facilities have to cease function, but the small makers are able to continue their practices,” she says. “It's almost like a pre-industrial revolution moment."

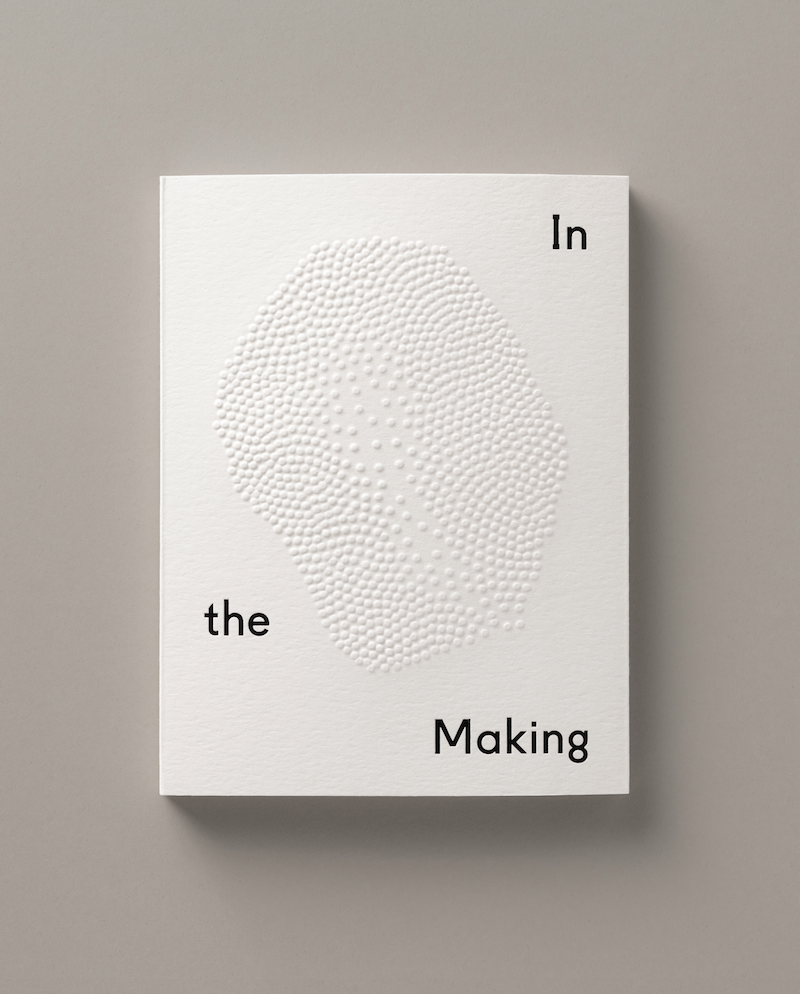

Carroll is the editor of a recently released book, In the Making, that compiles interviews with contemporary artisans, ranging from Brooklyn, New York–based plaster maestro Stephen Antonson to Philadelphia glassworker John Pomp. The book was produced in conjunction with San Francisco showroom De Sousa Hughes as a celebration of two decades in business; however, it’s just as much a celebration of contemporary craft, a kind of yearbook for some of the design trade’s most recognized names.

Business of Home chatted with Carroll about the trait all makers have in common, how they’re faring in the time of COVID-19, and the process of creating the book (which, with a limited 1,500-copy run and a nail-embossed cover referencing a work by German sculptor Günther Uecker, itself feels much like a maker’s object).

What defines maker for you? What does that word mean today?

There’s a spectrum. You have single makers, like Kristin Colombano of Fog & Fury, who is literally in her San Francisco studio working on handmade felted fabrics. And then you have Altura Furniture, a team of six guys working in a studio out of Portland, Oregon. Then that goes all the way up to a big house like Liaigre. They’re all around the world, but they’re still employing craftspeople doing each of their disciplines.

The last decade has felt like a good one for makers—I feel like the design media pays more attention to the concept than ever. Why do you think that is?

Maybe it’s a result of the spotlight shifting to them. There have always been makers who have worked in these traditions, but it’s started to intersect with the zeitgeist—people reacting to the digital revolution and feeling like our generation still needs to connect with things that are sensual and tactile.

What sets apart the really successful makers from the hobbyists?

One of the things that really gave me faith coming out of [putting together the book] was that there are showrooms like De Sousa Hughes where you can be represented as a maker, take care of your family, support a team of artisans and have a lifelong career. [But] you have to be able to put things into production and continue to innovate and create new pieces over longer periods of time.

I think John Pomp’s an amazing example of this. He’s been able to systematize production so that there’s repeatability, so he can have this whole team and international presence. But he himself is still glassblowing all the time. To me that’s a miracle.

What are some of the business challenges for makers?

There’s this beautiful dance between creating something that’s a singular piece each time and having an understanding and appreciation on the designer side that there could be variations on a piece. An appreciation that the woodgrain is going to be slightly different each time—that wabi-sabi sensibility. Sometimes that can be a challenge in educating people: This is handmade, there’s going to be a little bit of variation.

What about the makers themselves—did they share any traits in common?

I loved the fact that these are people who would be doing this no matter what. I just interviewed [California-based makers] Randy Tuell and Victoria Reynolds, who said, “We’re basically unemployable. We would be doing this regardless.”

One of the things that’s always fascinated me about makers is that they’re these idiosyncratic people often working in gritty workshops, but they make expensive objects and their clients tend to be extremely affluent. It’s an interesting dichotomy.

When you look at the tradition of bespoke or handmade furniture, it hasn’t changed a lot since the 17th century; it’s always been this special thing [with a certain kind of patronage] like artists and the art world.

When any client or homeowner ends up looking at the process and what it takes to actually make that piece, you see that the pricing of it is actually not unreasonable. It literally takes weeks and weeks to conceptualize the piece and illustrate it and create the mold from hand and then cast and refine and patinate it. … It’s an art! Part of what we were hoping to achieve with the book was to dive deeply into the rigor, the physicality, and mental and bodily intelligence it takes just to make one of these pieces.

I suppose one reason that makers are enjoying success right now is that there are so many more ways to show the process, with social media, than there were two decades ago.

Totally. Especially right now.

Speaking of right now: How are makers faring in the thick of the COVID-19 era?

When things started, we all thought it would come to a screeching halt. At least [in San Francisco], a lot of designers are continuing to work on their projects. At least when orders are getting placed, they can start making deposits, they can do all the conceptual and rendering work, even if they can’t produce everything and ship it. So I think makers are really relieved that they’re able to keep orders coming in.

Homepage photo: Plaster artisan Stephen Antonson | Lucas Allen