David Kleinberg cuts straight to the point when asked why he decided to name equity partners at his interior design firm: “My impending old age,” he laughs. Jokes aside, Kleinberg wanted to know that his firm would continue on without him.

“I have people who have worked here for 10, 12, 16 years who are very essential in the growth and ongoing success of the company,” he says. “The logical thing to do was to have a very clear understanding of what the company would look like at the time I fell off my perch.”

Kleinberg had been on the other side of the equation during his 16-year tenure at Parish-Hadley, and saw firsthand how a firm can fall apart when the principal is no longer in the picture. “We had at various times had conversations about the long-term designers becoming limited equity partners, but it never came to anything,” he says. “It was always in the back of my head, so this was an easy continuation of a conversation I had had 20 years prior.”

It’s an issue more and more designers are grappling with. “Interior designers probably don’t start their businesses thinking that it will go or will need to go beyond themselves,” says Peter Piven, a management consultant to design professionals with two decades of experience. It’s only after they’ve grown their firm that designers start to pay closer attention to what the future looks like for their employees and clients, or, as Piven notes (and Kleinberg made clear), “they may have begun to recognize their own mortality.”

To understand the key points a designer needs to consider when thinking about succession, we spoke to four veterans who have put plans in place for the future of their firms.

Date Before You Marry

There’s one major commonality with every designer spoken to: They had a long working relationship (usually 10-plus years) with the person (or people) they named partner. “It’s akin to dating,” says Jamie Drake, who merged his firm with Caleb Anderson’s in 2015. “Get to know a person well before proposing marriage.”

At the time of the merger, Drake and Anderson had known each other for eight years; Anderson had started as a summer intern, then worked for three years at Drake Design Associates. “If you know a candidate well, then you need to trust your gut and your knowledge of that person’s strengths and weaknesses,” says Drake.

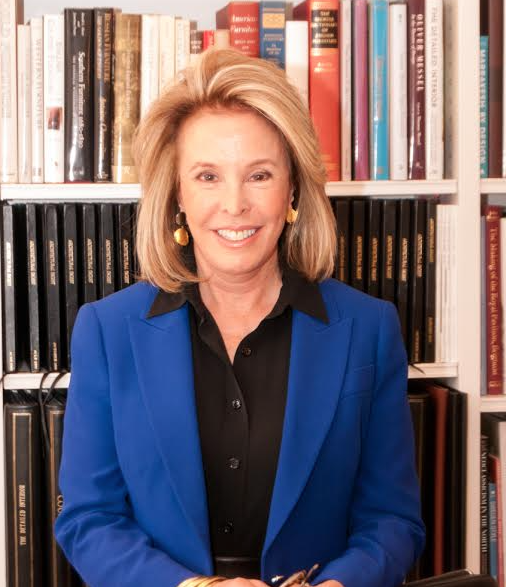

Bunny Williams had worked with Elizabeth Lawrence for more than a decade before naming her partner. “If you’ve worked with someone for 14 years,” says Williams, “you’ve seen them handle project after project. You see how they manage clients, how they deal with the back part of the business. And when you see all of that work out really well, you know you’ve got somebody that can carry on on their own. We had the courtship for long enough, it was time to cement it.”

Emphasize Loyalty and Longevity With All Employees

It’s not just the potential partners that should feel a sense of responsibility to the firm; it’s an ethos that should be cultivated across the board. “Whenever I interviewed people, I always talked about wanting employees to be in it for the long haul,” says Kleinberg. “I wanted people who felt that they could grow their careers here.”

To incentivize employees to stick around, Cullman & Kravis, which adopted a small-group management structure in 2015, offers an employee stock option plan to give them a vested interest in the company. “Designers should realize that design is collaborative and give credit to their colleagues from day one,” says co-founder Ellie Cullman.

Ask Yourself the Right Questions

There’s a lot a designer should take into consideration when thinking about a succession plan. Piven offers a starter list of questions to kick off the process: “Do they have employees who they see as future partners? Can they be educated and mentored? Are they entrepreneurial? If not, are they willing to recruit someone who has those qualities? Are they willing to share ownership and profits? Do they have dates in mind for divestiture and retirement? Do they wish to consider other options?”

The question-asking goes for both parties. Swartz says that young designers need to fully understand the commitment before agreeing to a partnership. “What are the additional responsibilities you’ll be taking on, and do you actually want to take them on?” she asks. “All of a sudden you’re involved in so many more things.”

Do It for the People, Not Your Name

Succession planning shouldn’t be driven by vanity. “My goal wasn’t truly legacy driven at all, by the literal definition of the word,” says Drake. “I wasn’t concerned with my name going on in perpetuity.” It’s a sentiment echoed by Williams and Kleinberg.

A designer needs to look at succession planning from a business perspective, and think about what will be best for the people who have supported the company and helped it grow. “You want to give people a sense of permanence,” says Kleinberg.

“Designers have to see beyond their ego about it,” says Kleinberg. Creating a path forward is about incentivizing employees to stick around. “People spend a lot of their lives working,” he says. “And if they stay at a company, it’s nice to know that it isn’t going to disappear when the principal disappears.”