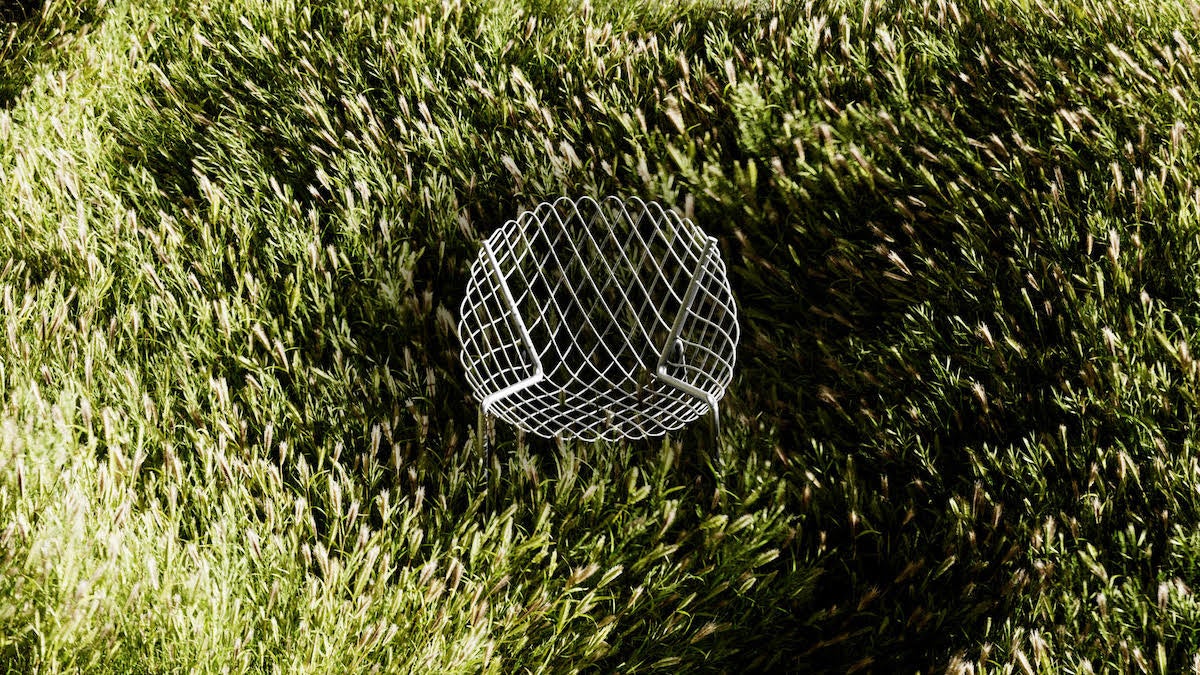

Last week, the Los Angeles–based furniture startup Dims released a line of outdoor furniture by Dutch designer Christian Heikoop, called the Logos collection, into the (physical) world. Soon, it will release the same collection into the virtual world—its first round of NFTs. “Crypto and smart contracts had been on our radar for years, but once NFTs took center stage last year, we started to understand how some of the technology could be harnessed for what we do,” says Eugene Kim, Dims’s founder and CEO.

For the uninitiated, NFT stands for “non-fungible token.” The technical explanation: NFTs are fixed records on a “blockchain”—a network of connected computers that create an unchangeable, unhackable ledger of transactions (cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin work on a blockchain). If the preceding sentence flew far, far over your head, think of NFTs as digital collectibles. These are online baseball cards your mom can’t throw away.

NFTs have mostly made headlines for their crazy prices, driven up by speculation. Maybe you heard about digital artist Beeple auctioning his piece Everydays for $69 million? Or perhaps you caught wind of the Bored Ape Yacht Club, a series of 10,000 cartoon ape NFTs that sell for upwards of $200,000 each? (Jimmy Fallon, Justin Bieber and Paris Hilton all own one.)

Those are the flashy stories that grab headlines. Out of the limelight, NFTs are a playground for innovation. That’s true even in a famously old-school category like furniture, where many experiments connect the digital world with the physical. For example, early last year 3D artist Andrés Reisinger designed a series of “impossible” pieces of furniture that supposedly could only exist in the digital realm, and pocketed $450,000 when he sold them as NFTs. Soon after, Danish design brand Moooi figured out how to manufacture one of the pieces and began selling it. (At $3,400, the real thing goes for far less than its NFT counterpart.) Only months later, Christie’s auctioned off a collection of digital-only furniture by Misha Kahn as NFTs; each lot came with specifications allowing the owner to 3D print a physical version of the design.

Into this burgeoning landscape comes Dims. The brand is releasing a collection of 2,000 NFTs in stages, with a starting price of $100 for the first batch. Generally, NFTs can only be purchased with cryptocurrency, but Dims partnered with a service called Venly that intermediates the transaction so customers can buy in with good old-fashioned American dollars.

Most NFT projects resemble art or collectibles. Dims’s launch has some of the same characteristics—a limited run, a shimmering animated GIF—but puts them to a different use. Each NFT is technically a collectible, yet it is also a permanent coupon entitling the holder to 15 percent off all Dims merchandise for life (including the real-life Logos chair, which retails for $595). Owners can keep the NFT or sell it on the open market.

“We’re intrigued by the potential impact of purchasers being able to easily sell or transfer their Logos NFTs—possibly even for a profit—which could power an organic referral mechanism,” says Kim.

The proceeds Dims hopes to raise from the sale, says Kim, will go toward recovering the cost of engineering, tooling and prototyping the chair itself. In that respect, the NFT sale is something like a high-tech, after-the-fact Kickstarter campaign—one that could serve as a model for future product launches.

The brand already has a unique production model, only manufacturing individual pieces once it amasses preorders directly from consumers. If Dims can find success selling furniture NFTs, it will be able to cover both development and manufacturing costs before putting in a single order with its workshops. “If we’re able to create the scaffolding for this to work for us one time,” says Kim. “I believe that it enables us in the future to support a renaissance in emerging design. And not just (for Dims)—other designers will be able to crowdfund new projects into life without having to find a brand to finance them.”

Kim is no stranger to alternative modes of funding. Last year, he raised more than $600,000 through the crowd investing platform Republic, which allows entrepreneurs to auction off fractional shares of their business in exchange for cash. “The last company I worked for before starting Dims was a crowdfunding company,” says Kim. “It was very inspiring. We were working with people to bring new things into the world without having to beg rich people for money. That feeling has never left.”

Indeed, up until only a week ago, Kim was pursuing a version of the NFT campaign that felt more explicitly like an investment and fundraising arrangement. In the previous incarnation, buyers of the Logos NFTs bought rights to royalties on each unit sold. Once the chairs started making money, holders would receive direct payments in cryptocurrency.

Kim says he paused that model at the last minute to wait for more clarity on how NFTs would be regulated by the government. But the vision is still a compelling one, he says. It’s not hard to see why. If designers and brands can sell NFTs to fund the development cost of a project, and the holders of the NFTs receive royalties automatically, you’d have a very tidy system. If shoppers one day buy Dims with crypto, it gets even tidier—a kind of closed loop of funding and purchasing that would require very little middle management.

“It’s not going to happen overnight, but I absolutely think a version of [that system] is going to happen,” says Kim. “Crypto is here to stay, and the technology is game changing.”

Homepage photo: Dims’s Logos NFT | Courtesy of Dims