In Business of Home’s series Shop Talk, we chat with owners of home furnishings stores across the country to hear about their hard-won lessons and their challenges, big and small—and to ask what they see for the future of small industry businesses like theirs.

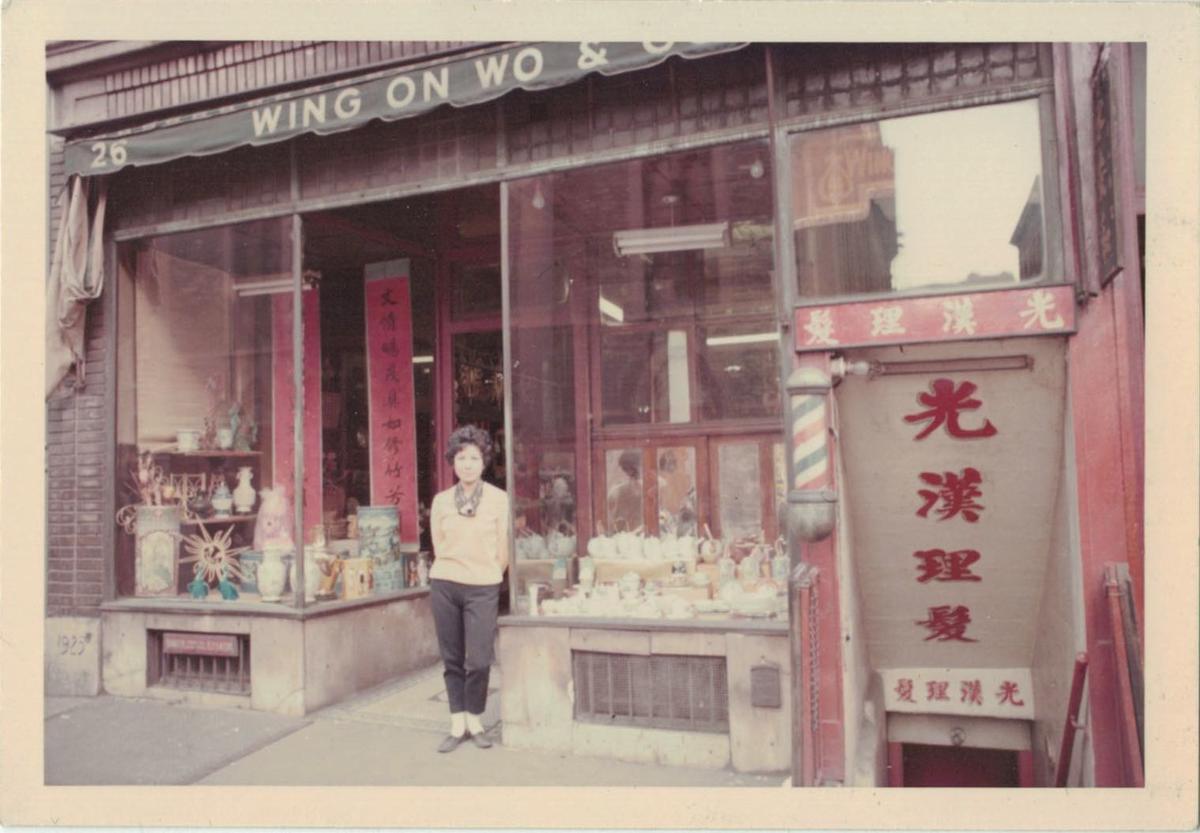

This week, retailer Mei Lum discusses her role as the fifth generation to run the iconic store Wing on Wo, the oldest continuously operating store in New York’s Chinatown. For 130 years, the store has offered a taste of home to the neighborhood, first via canned goods and hot food, and later with imported porcelain and home accessories. Since taking over in 2016, Lum has focused on buttressing the business from gentrification and creating a community initiative, the WOW Project, which seeks to preserve Chinatown’s creative culture through projects like public art and events, youth mentorship and mutual aid.

What’s the background of your store and your role there?

The shop has been in my family since 1890. When I was small, it was under my grandmother’s wing, and she was sourcing all of her porcelain from Hong Kong with my grandfather. I would come to the shop after school, and my grandmother would be cooking dinner and an afternoon snack for me in the small kitchen in the back. As customers came in, I would work the register and help out where needed.

When did you take over? Did you always know that’s what you were going to do?

The shop has always been a space where I spent time with my family—our informal living room. Turning it into my workplace has been a journey, working in collaboration with my family and trying to find our stride. In 2016, my family came to a pivotal moment of potentially shutting our doors and walking out into the sunset. I had a plan of going to graduate school for international development, and never really imagined myself becoming a small business owner.

My approach to running Wing on Wo is very nontraditional. I needed to do it on my own terms, figure out ways to integrate a social mission, and make sure we were considering what was happening here in Chinatown. At the time I took over, I also founded a community initiative called the WOW Project, which uses arts and activism to push back against cultural displacement and gentrification.

Chinatown has a very strong legacy of patriarchal systems, and I don’t think it’s common to see a female, femme, queer, trans-owned business. Looking back, that was an insecurity of mine. I didn’t expect to do this. I considered, many times over, going to business school because I felt like I needed that accolade to really call myself a small business owner.

What are some of the displacement issues in Chinatown?

A lot of longtime residents are being pushed out of their homes because they’re paying a rent-controlled or rent-stabilized price, and the landlord sees those units as being undervalued. We see a lot of longtime businesses pushed out or shuttered because there’s no next generation to take over, and that leaves a lot of empty storefronts. We’ve seen an influx of art galleries popping up, which is a common sign of gentrification—an easy way for landlords to clear out a commercial space and hike up the rent, because art galleries just paint the walls white and hang art. It’s pretty easy in terms of maintenance. The WOW Project is also addressing cultural displacement: These art galleries think they’re bringing arts and culture, but in fact, there has been a century of that foundation built by the people who established Chinatown. [We are] making sure that this culture and these traditions don’t get lost, and that there’s continuity.

Do you have relationships with some of the other long-standing businesses in Chinatown?

Because I do a lot of community work and I'm quite involved, it feels natural to have relationships with these folks. And because these families have been in the neighborhood through generations, the relationship is held with different members of my family and almost gets passed down. We all say hello on the street and catch up when we bump into each other. Especially during COVID, our community banded together for the advocacy of economic relief here in Chinatown, because if we didn't, we wouldn't have gotten access to funds, especially with the language barrier and the challenges that come with being a cash economy. I always try to uplift and collaborate with the other businesses, and it feels really special to be able to do that.

How would you describe the vibe of the store?

When I stepped in, I really didn’t want to change it too much. I wanted to make sure that my grandmother, who’s 91, and my great aunt, Betty, who used to be a co-owner of the business, were still able to recognize this place and feel at home. So we continued specializing in Chinese porcelain. A lot of our pieces are hand-painted. I would say it’s about 20 percent my grandparents’ pieces [sourced] from Hong Kong, and the other 80 percent is porcelain sourced from the porcelain capital of China, called Jingdezhen, by me and the Wing on Wo director of product, Nate Brown. Up until 2019, we were going at least once or twice a year to hand-pick the porcelain that fit into the aesthetic of the shop, that felt authentic to the history and legacy.

Because the porcelain my grandmother sourced was basically from the 1980s, a lot of those patterns are not being produced anymore. So we go to different flea markets and storage spaces and rummage through basically dead stock that folks in Jingdezhen have acquired. We also work with individual artists based there—young ceramicists who are making their own work and reinterpreting different traditional styles of Chinese porcelain. Then we work with small studios to make custom pieces reinterpreting traditional elements to be more modern.

This holiday season, we’ll be launching our very first artists’ line, collaborating with New York–based artists to create unique pieces and producing them with artisans in Jingdezhen. The collection has a theme of ritual and ceremony.

Who is your typical customer?

We’ve really homed in on our customer base in the past two-ish years. Our demographic is predominantly young, like a 20- or 30-something Asian diasporic person interested in learning more and connecting with cultural identity. That's something special that WOW does—we’re not only selling pieces and porcelain, we’re also connecting to a larger conversation about identity, sense of belonging, living memory, and how pieces go beyond just material use.

What’s one of your favorite items in the store right now?

I've always been obsessed with gourds because of their symbolism and cultural significance. They signify the origin of life, and have such an interesting form and shape. We recently got in these beautifully hand-painted gourd vases that I think are incredible and fun and playful.

Is there a specific product that you can’t keep in stock? Something that customers always gravitate toward?

We have these really fun Tang lady plates, based on Tang Dynasty women, made by an artist in Jingdezhen who wants to stay anonymous. They all have expressions of sass and joy. They’re also topless. So, a lot of people think that they’re so fun. I use my Tang lady plate in the morning, and it just makes me feel happy and sets a really good tone for the rest of the day. Those are super, super popular. We’ve restocked them five times already and they always sell out.

What advice would you give yourself if you could go back to 2016, when you took over the business?

Sometimes working at Wing on Wo feels like I’m working at a hundred-year-old startup that’s just waking up after taking a long break. Speaking to the level of confidence and trust—or lack of trust—that I had in myself in the beginning, I would probably say: “Trust your gut. Trust your intuition. It’s OK to make mistakes.” Over time, I’ve learned that trying things out is the only way that you’re able to know what works and what doesn’t.

What’s the store’s biggest everyday challenge, and biggest existential crisis?

I hold a lot of different roles in the shop—I am the director of the WOW Project, and I’m also the shop’s strategy buyer and marketing person—so I think balancing those and making sure that I’m able to fully show up for the people I work with is always a challenge. Making sure that my family feels valued [and] engaged and are working on things that they enjoy has been a journey, for sure.

An existential challenge is that I really want to hire somebody outside of the family. My mom runs our e-comm; my dad is the shipping and packing department. We all run the retail storefront on the weekend. It wasn’t until COVID and the lockdown that we were able to really double down on our e-comm. Now it feels like we have twice the amount of work and the same team. It’s come to a point where we really need help in order to scale and grow. But who is that? Who can join the family dynamic of real talk all the time, of random disagreements? That integration worries me a lot, but I think I’m just going to have to pull off the Band-Aid and go for it before the holiday season. I’m confronting that existential crisis.

The e-comm experience on your website is just gorgeous. What was it like to invest in that?

I met the photographer we work with a few years back. She was emerging at the time, too, and we’ve kind of found our stride together, which felt really collaborative and generative. The challenge of building our e-comm platform, as well as social media, has been: How do we authentically translate our story in a way that feels like who we are, instead of like we’re performing? How do we come off as modern but also traditional? It was tough in terms of color palette, photo style. Our website now, which we relaunched a few months ago, feels like the closest to what we’re really working towards.

Is there something you wish more customers understood about your business?

I feel like our customer base knows who we are, but I sometimes get the occasional total misunderstanding [where I have to clarify] that we’re not a big company—we are literally four people working behind the scenes. We’re not Amazon; we can’t fill orders so quickly or immediately. If you really want to support small businesses, you have to also open your mind to what it looks like behind the curtain.

You’ve talked about gentrification, but are there other New York–specific challenges other retailers might not know about?

The way that Chinatown is framed to outside perspectives is that we are a tourist destination—it’s cheap here, the quality is low, we’re selling pieces that were produced in China. We do have folks from out of town that don’t know who we are and stumble upon us. We sell high-quality products, there are actually individuals making our pieces, and we don’t bargain. Coming up against the stereotypes specific to Chinatown has been challenging in the past, but I think it’s also part of the education piece—how we talk about our products and how we source them [is part of] resisting that stereotype.

What do you think the future is of small businesses like yours?

It feels like there is another chapter to our legacy in the ways we’ve updated with e-comm and social media. I think small businesses need to continually adapt to the times, while also not losing who they are, and that’s hard. Across from us is Hop Kee, which is one of the oldest restaurants here in the neighborhood. Through the pandemic, they said, “We do not do online orders. We’re not going to use apps like Seamless or Grubhub, because that goes against our ecosystem.” I totally get it, but also there is a point of survival, of needing to make ends meet, needing to pay the bills. I would love to see a way for small businesses to have a space in New York, to be prototyped and incubated in a way that feels less high-stakes. It’s especially hard in New York to rent a storefront and just try it out, because the level of overhead and investment is so much higher than in other cities.

What’s a great day as a shop owner?

I take care of my grandmother and make her lunch every day. Engaging her in the process of running the business and seeing the joy on her face is one of my best days. I started this series called “Po’s Picks” during the thick of the pandemic, when I featured her favorite pieces in the shop and made it a weekly Instagram story series. Filming those was really fun, light and playful.

Homepage photo: The interior of Wing on Wo | Photo by Ricky Rhodes