At Business of Home, we pride ourselves on covering the wide world of design, from Italy to Indiana. Still, it was particularly thrilling to call Mallory Solomon, founder of Salam Hello, and reach her in a village outside of Kalaat M’Gouna, a small city five hours southeast of Marrakech. Solomon, an American former advertising executive who normally lives in Brooklyn, has been stuck in Morocco since mid-March.

“Trump had banned all flights from Europe. My family called, and they were like, ‘You better get home.’” Looking at rising infection rates in New York, Solomon had her doubts. Forty-eight hours later, it was too late, anyway—the Moroccan government had closed its international borders.

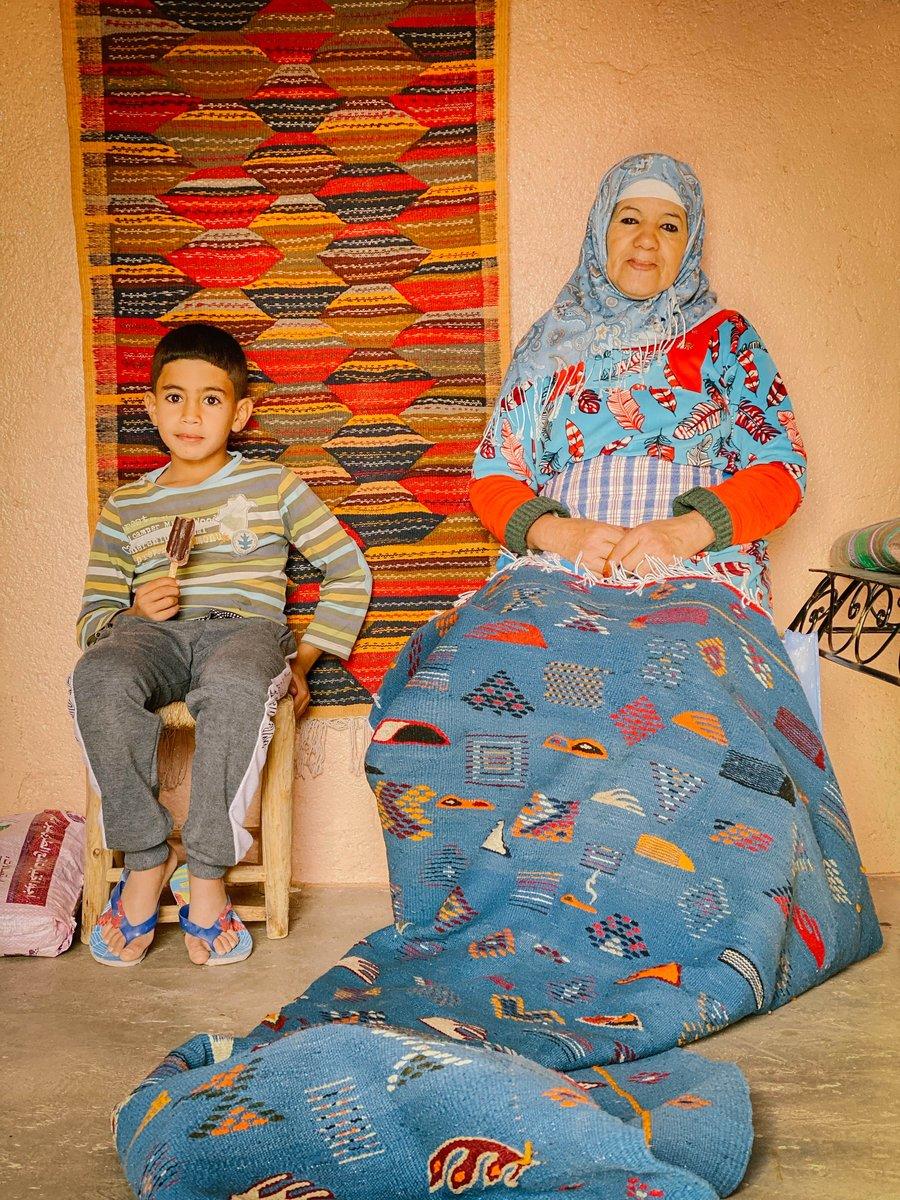

For Solomon, it wasn’t an entirely unwelcome development—she’s been using the time to connect with and build up Salam Hello’s talent pool. Her company, founded just last year, aims to bring together two parties who rarely meet face to face: Moroccan women weavers and the people who buy their rugs.

“When I came to Morocco as a tourist [in 2018], I, like most people, was buying rugs from bigger cities. I would walk into the souks, and it was always a man selling me the rug with the story of, ‘It was made by this woman, here’s the village it came from.’ But they couldn’t tell me any more about the woman or the history behind it,” says Solomon. “I left with a feeling of: Why can’t we connect with the women, or why aren’t the women in a power position to be selling these rugs?”

After digging a little bit, Solomon uncovered a troubling system. Berber women in remote villages weave the rugs, relying on traditions passed down for generations. Then, in small-town markets, brokers buy the rugs cheaply, sometimes by coordinating their efforts to underbid and drive prices down. From there, the rug is marked up several times before eventually being sold to a tourist. Brokers and shop owners pocket much of the profit, while most of the work is done by the original artisan.

Solomon devised a simple workaround, buying from the weavers directly and selling online. It’s the classic cut-out-the-middlemen disruptor’s playbook, but there’s a crucial twist. Instead of passing on a steep discount to consumers, Solomon’s aim is to simply pay the weavers more for their work. “I buy the rug from the weaver for what the souks will sell it to tourists for,” she says.

For buyers, the appeal of Salam Hello is less a fantastic deal and more the peace of mind that comes with an ethically sourced product—and the pleasure of knowing the name of the person who made it. (The point is driven home on the brand’s website, where individual rugs are named after their makers, e.g.: Latifa’s Everlasting Hanbel, or Naima’s Sun-Drenched Beni Ourain.)

Another crucial difference between Salam Hello and a more traditional retail industry disruptor: Unlike manufacturing toothbrushes or eyeglasses, it’s fantastically difficult to streamline an enterprise like traditional weaving. The network is spread out over a wide region (Solomon meets all of the artisans in person, then communicates through a translator via WhatsApp video calls), and most of the artisans don’t work in the standardized dimensions that American consumers are used to. “It’s always funny when you find a ‘vintage’ rug that just happens to be 8x10,” she says wryly. “It’s not vintage.”

Solomon is hopeful that a new customization program will make the process easier on both sides of the equation—buyers can get the sizes they want, and the weavers will start to see a demand for certain dimensions and change their process accordingly. She also hopes that a custom program will appeal to the interior designer audience that she’s looking to cultivate. Salam Hello does offer a trade discount of 15 percent—not as deep as some purveyors, but wholesale-style markups would be antithetical to Solomon’s artisan-focused approach.

“The clients that are good for Salam Hello are the ones who care about where each product came from. If they care about that story, they’ll want this product,” she says.

Looking ahead, Solomon hopes to expand the business—no easy task given the degree to which the company has been built on direct relationships. Then, of course, there are vested interests (brokers and souk dealers) who would rather Solomon weren’t there at all. She says she’s been followed by a broker, and that she’s gotten suspicious WhatsApp messages that seem to be fishing for information. That, coupled with the delicate issues that arise whenever a Westerner does business in another culture, are factors she is mindful of.

“I have told the women explicitly: ‘I don’t want you to only sell to me.’ They need to make more money, and if they have the ability to sell to other people, they can and they should if they want to,” she says. “I want to give them the tools to empower them but not force my values onto them, and to be respectful of what they want.”

However, she says the greatest danger to traditional rug weaving isn’t so much outside intervention, but generational death. As the teenage daughters of weavers come of age in an interconnected world, they are increasingly abandoning the practice in favor of more “modern” careers. And with the system working the way it does, says Solomon, why wouldn’t they?

“They’ll say, ‘Yeah, of course I know all about [weaving], but I’m not going to do it.’ Because they see that it’s really hard work, and a lot of them aren’t getting paid fairly for it.”

Homepage photo: Courtesy of Salam Hello