The signs are in the air, and people are starting to talk. The estimate-shattering Mario Buatta auction. “Grandmillennial” becoming a thing. The Shade Store collaborating with Samuel & Sons. Is vibrant, joyous traditionalism about to take over the world?

If it is, Annabel Westman has picked her moment well. Westman, an English textile historian and author, has just published a definitive study on the history of British trimming, Fringe, Frog & Tassel: The Art of the Trimmings-Maker in Interior Decoration. The book, which charts over 600 years, can be appreciated both as an academic text and as pure eye candy. For those who want to dive deep, there’s plenty. If you’re not a big reader, but looking for gorgeous tassel extravagance, there’s plenty of that too.

Business of Home spoke with Westman to hear about her research methods, the surprising political dimension of lacemaking, and what exactly a friar’s knot is.

You’ve been studying trims and tassels for a long time. Was there a jumping-off point? The trimming that started it all?

It was a particular curtain at Osterley House. I was working alongside a person who was doing the conservation … it was wonderful. It was such an attractive way of finishing an edge, and I thought, Ooh! I just got this thrill of how things could look—and how things don’t look today.

In your book, you reprint classic paintings, but instead of discussing the art historical significance, you’re zooming in to see the tassels and trimmings in the background. I loved that. Tell me about your research process.

Well, when you look at a painting you think—is that actually real? Is the painter just making up the trimmings? Are they just making this look pretty, or did this actually happen? In some cases, it was just making an effective design, but in many cases, they are quite true to what was created. The fascination I found was matching up original documentation with paintings—it brought the paintings alive.

You would find a painting of a historical home, and then find the actual bill for the work that was done, and match the two together?

I’ve been terribly privileged to have been able to examine all these things—in the future they can’t be studied, because they don’t exist anymore. I remember them being in situ, I’ve seen them being retired, I found them in the drawers of stately homes. So I feel as though I’m on the end of a line.

One interesting aspect of the trimming trade was that originally, it was a female-dominated profession. Women owned their own businesses. Then around 1550, men took over.

In England in the 16th century, life had become more stable. When life becomes more stable, more attention is given to decoration. More people were paying attention and buying trimmings, and when men realized there was money to be made in this trade, they took over. Women ended up working for men—whereas before they had employed people.

There was also this political dimension, where you had French trimming makers coming into the trade, and English makers fearing the loss of work. It feels not unlike a contemporary debate about immigration and jobs.

Let’s say the Brexiteers missed a trick there. With anything, when people fear for their jobs, they get rather violent. When these immigrants were fleeing religious persecution in their own countries, they settled here, and some of them were bringing new ideas, and the English felt threatened.

Tell me about the economics aspect of it. It wasn’t cheap.

Trimmings was a luxury trade, but the expense was in the materials, not in the work. The original trimmings makers were called lacemen. They could be successful and make a lot of money, but they employed people—often in the home, who weren’t paid much at all.

Forgive the comparison, but it’s almost like the gig economy is today—you can work from anywhere!

Well, with gold thread, maybe they wouldn’t. Gold thread was quite expensive and that would have been monitored very carefully. But trimmings weren’t made in factories. There’s a quote [from 1747] in the beginning of the book: “It is chiefly done by women, upon the hand, who make a very handsome livelihood of it, if they are not initiated into the mystery of gin-drinking.”

Which means: You could do it from home, unless they hit the bottle. It is a trade that’s very flexible, and it was done by children, by women, by old men who needed to earn a penny or two.

You cover a lot of ground—from 1320 to 1970. Tell me about big shifts in style for trimming.

In 1660, with the restoration of the monarchy, we went completely wild—we’d been 20 years in austerity and suddenly there was this desire to be colorful and to introduce new things. A lot of things were coming in from France. We had Louis XIV on the throne in France, we had Charles II on the throne here in England, who had lived in foreign courts and wanted to emulate foreign courts. It was a period of really vibrant trimming.

What’s another?

The discovery of Pompeii and Herculaneum in the second half of the 18th century … paintings on the wall showed trimming with droplets. The whole idea in the second half of the 18th century, what they were seeing in paintings on walls in these cities, they were copying. The style of trimmings that came at the very end of the 18th century had its origins in the classical world.

One of my favorite parts of the book is the glossary. There’s no standardized vocabulary for these techniques, so you end up with all these wonderful, unique terms like lizarding and none-so-pretty. What’s your favorite?

My favorite is friar’s knot. One of the reasons for the decline in trimmings is we don’t have any proper terminology. I think that led to the detriment of the art. But there really never has been—each trimmings maker would use different terms for the same thing.

I kept coming across the term friar’s knot in documentation and kept thinking, What on earth does this mean? I was fortunate enough to come across a reference and I knew where I could find the original trimming that it was describing. I looked at the trimming and thought, Gosh, that’s what this is!

What is a friar’s knot?

Strands of floss silk which are knotted. Only a friar wears a knotted belt—the trimming is copied from that. But then in the 18th century, with friars not being around much anymore, they came to be known as different things. Sprigs. Or flies—like a fisherman’s fly. Now they’re called faggots [Ed. note: in England, the term faggot refers to a bundle of sticks.] It’s a term that has gradually changed.

The book stops in 1970. What led to the decline of intricate trimming?

I thought, Where do I stop? I could have stopped in 1914—[during] the First World War, it began to decline. You’ve got the end of the Edwardian era, but then you get into art deco and they weren’t popular. But there is a really interesting strand that I wanted to record—alongside the Arts and Crafts movement and art deco, whilst they discouraged a lot of trimmings, there were people who were still encouraging them. There was this growth of connoisseurship and historicism. People began to look to the past and began to want to re-create it. You’d have a wonderful re-creation of a 17th-century interior done in 1912.

Were there specific people who were keeping the traditions alive?

You had the American tastemakers, particularly Nancy Lancaster, who came over to England and reintroduced color. Instead of just copying, she brought in a new color inspiration and design sense that reinvigorated that country house style. She and other ladies of her period continued it. And then Sibyl Colefax and John Fowler became involved—I ended it in the ’70s because John Fowler died in 1977. He loved trimmings—Nancy Lancaster said he was terribly interested in “the extras,” and all of his designs have trimmings. When he died, it was really the end of an era.

Do you think intricate trimming will come back?

There are signs that it’s coming back, in different ways. … There are certain designers who are using them. It’s a question of whether people will pay for real extravagance of what they can be. It truly is an art form.

Do you have trimmings in your own home?

I have one or two tassels hanging here and there. … I’m not a collector, but I do have a few. They’re wonderful things just to look at.

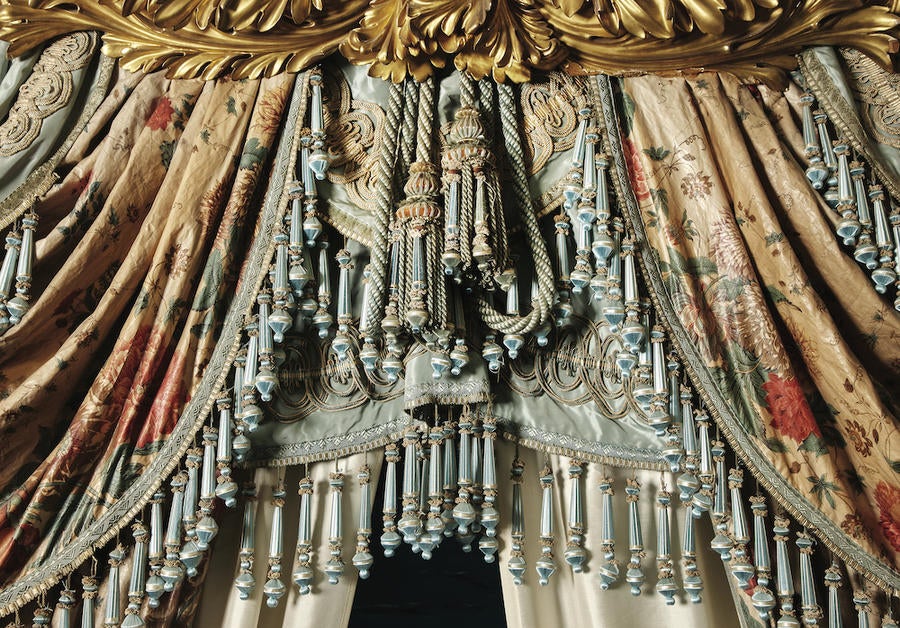

Homepage image: Detail of silk, vellum and wire ‘festoon’ fringe on Queen Elizabeth’s bed, c. 1685 (pages 56–57) | © National Trust