Gustavo Reyes Gonzalez noticed his first symptoms in 2020: a persistent cough and shortness of breath, originally misdiagnosed as pneumonia. It would take about a year before the 34-year-old stonecutter learned the true nature of his diagnosis.

“[The pulmonologist] told me I had silicosis. I asked him what that was, and he told me, ‘You’re sick because of your work, because you’ve been breathing in silica,’” says Reyes Gonzalez. “I asked him, ‘What are we going to do? Is there any treatment?’ and he said, ‘There’s nothing we can do for you, because there is no cure for this disease.’”

Silicosis is nothing new—in fact, it’s been around since ancient times. The occupational illness, which has long afflicted quarrymen and miners, is contracted through the cutting or grinding of stone, which releases microscopic particles of crystalline silica dust into the air. When inhaled, prolonged exposure to this type of silica can cause damage to the lungs, including inflammation, permanent scarring and eventual respiratory failure. For centuries, it was a disease relegated to workers in their old age who had accumulated a lifetime of exposure. That’s changed since artificial stone hit the market in the 1990s.

“I’ve seen a few cases of silicosis in miners in the American West, but those have mostly been people in their 60s and 70s who have pretty mild disease and can live with [it],” says Robert Harrison, a physician at UCSF Health who specializes in occupational diseases. “What’s different about silicosis from engineered or artificial stone is that the disease is happening in relatively young people, and it’s extremely severe.”

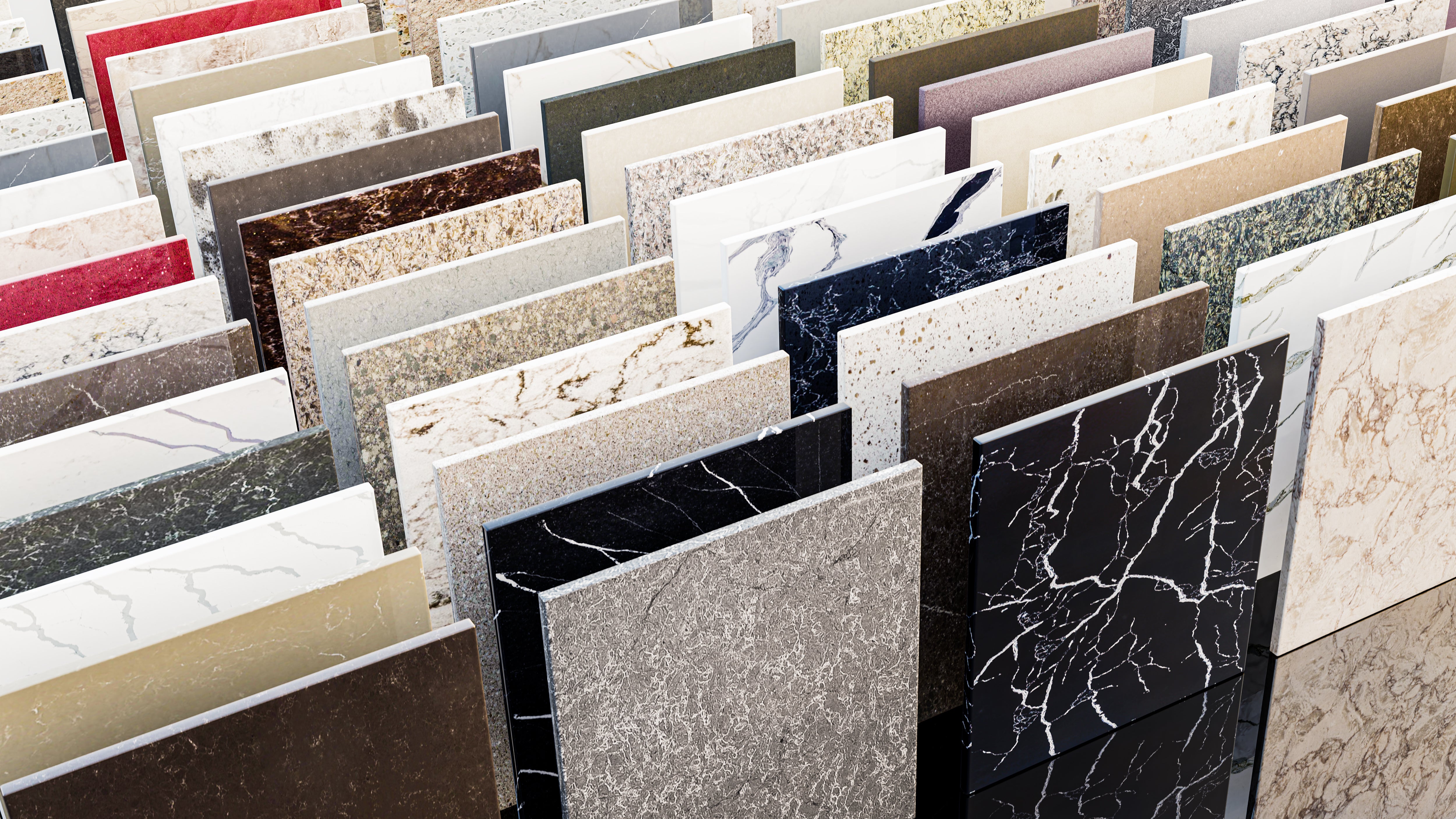

Compared to marble, which contains and releases little to no crystalline silica (less than 5 percent), or granite, which has a composition of 45 to 50 percent silica, artificial stone often comprises at least 90 percent—a jump that increases worker exposure drastically. For those who contract silicosis, it can be a death sentence.

On May 14, savvy strategist Ericka Saurit helps designers understand where Instagram fits into a holistic marketing program—and how to employ the platform to express what makes your business unique and use content to connect emotionally with your ideal clients. Click here to learn more and remember, workshops are free for BOH Insiders.

“When I got out of [the doctor’s office], I started thinking, ‘What am I going to do with my life?’” recalls Reyes Gonzalez. “I decided to keep working because I needed to save some money for what was coming. Actually, what I was doing was saving money for my funeral.”

While his medical journey is far from over, the events of this summer may lead to some financial relief. In what his legal team says is the first case of its kind to go to trial, the worker sued 34 manufacturers on the basis that their products are inherently hazardous and their safety warnings are insufficient. Last month, a Los Angeles County jury agreed, delivering a landmark decision in the case that awarded Reyes Gonzalez more than $52 million in damages and attributed partial liability to manufacturers Caesarstone USA (15 percent) and Cambria (10 percent) and distributor Color Marble (2.5 percent). While the case still awaits judgment—a process that will determine the exact dollar amounts liable parties must pay—and a likely appeals process, the decision could mean manufacturers are on the hook for millions.

“It is a complicated formula, based on both math and law. … I anticipate Cambria will pay around $11 million, Caesarstone around $13 million, and Color Marble around $8 million,” says attorney James Nevin, who is part of Reyes Gonzalez’s legal team.

Reyes Gonzalez is not alone. Health officials are discovering a startling number of silicosis cases cropping up across the country, many of them concentrated in California. As of August this year, the California Department of Public Health has identified 176 total cases of engineered-stone-related silicosis since 2019—counting at least 13 deaths and 19 individuals who have undergone lung transplants. As such, a slew of similar lawsuits are expected to hit the docket in the coming months: Brayton Purcell, one of the firms representing Reyes Gonzalez, is now managing 200 cases—including the first cases filed in Oregon, Washington and Colorado—while at least a dozen others are entering the court system. The firm’s youngest client is a 24-year-old worker already in need of a lung transplant.

According to manufacturers and legal experts, many of whom come down on different sides of the issue, the question of how to contain the growing silicosis epidemic is far thornier than it may seem. For the stone industry at large, it could be the start of a major inflection point.

After arriving in the U.S. from Mexico in 2007, Reyes Gonzalez found work as a stonecutter in Los Angeles through his brother, who taught him how to grind, polish and cut stone—at the time, mostly granite and marble. One day, a new kind of material came into the shop: an artificial stone slab, made by the company Caesarstone. At the time, that type of stone (also known as quartz, or engineered stone—not to be confused with natural quartzite slabs) made up only about 10 percent of the product that came into the shop, according to his estimate.

Over the next decade, those numbers would change radically. Around the country, engineered stone boomed in popularity, favored by consumers for its nonporous durability and lower price point compared to natural stone. By 2022, Reyes Gonzalez estimates that the shop where he worked was cutting 90 percent engineered stone.

Around that time, his health had declined so severely that he was forced to leave his job. One doctor estimated he had three to five years to live, while another placed his prognosis closer to one year. He credits his wife with saving his life: She managed to get her husband on a health insurance plan, and then the former stoneworker was referred to doctors at UCLA Medical Center and Cedars-Sinai, who were able to get him on the list for a double lung transplant. After a grueling nine-hour surgery, he finally got a new pair of lungs.

But the ordeal is not behind him. Reyes Gonzalez now has to take medicine daily for life, which puts him at a higher risk of contracting cancer (a side effect of the immunosuppressant medication used to prevent organ rejection), and his coughing fits damaged his stomach and diaphragm—which required an additional operation just a few weeks ago. All in all, his prognosis has been extended to 10 years.

Along with failing to provide proper protection and instruction, he blames stone manufacturers for hiding the risks of their products from workers. “They make the material. They know the contents of the material. They know what products are in the material,” says Reyes Gonzalez. “They should warn [us of] that, and they didn’t inform us anything about that.”

Manufacturers refute this claim, asserting that they’ve adhered to safety standards by attaching warning labels to their products and including information in the Safety Data Sheet, or SDS, that comes with each slab. But they also don’t believe the issue comes down to the product itself. Their stance is that silicosis is primarily a workplace safety concern—and that by following Occupational Safety and Health Administration requirements, artificial stone can be safely cut. Any punishment, they argue, should be levied against fabrication shops.

In at least one case, that’s precisely what happened. Last month, OSHA issued $1 million in fines against a small Chicago-based countertop maker, Florenza Marble & Granite Corp., after two employees in the company’s six-person fabrication facility contracted silicosis. An OSHA inspection revealed that the company did not have a safety program in place, leading to more than 30 health and safety violations.

In the case of Reyes Gonzalez, the fabricator shop that employed him, Silverio Stone Works, was not named by his legal team as a defendant in the case. This became a point of contention for Caesarstone, which went as far as suing owner Fernando Silverio Soto in an attempt to have him named as a defendant. In the final decision, the jury did also attribute partial blame to the employer, lumping the shop in with the remaining 70 percent of liability attributed to various other slab manufacturers and suppliers. (Reyes Gonzalez himself was also attributed 2.5 percent.)

In recent years, with the rise of silicosis cases and awareness, many manufacturers have ramped up their educational role in preventing the disease. Cambria, for example, established a program in 2005 in which fabricator partners are invited to attend the manufacturer’s learning center free of charge, with complimentary lodging and meals. The program, called Cambria University, is meant to share best practices around stone fabrication and installation, including dust control and material handling techniques that protect workers. Caesarstone has taken a slightly different tack in recent years, physically mailing out manuals and videos on health and safety guidelines to fabricators. In 2020, the company unveiled an online workplace safety resource, Master of Stone; Cosentino hosts a similar site called the Health & Safety Space.

Going beyond worker education and putting the impetus on fabricators to create stonecutting systems that are physically safer for their staff is a far bigger investment, requiring much more money, time and effort. Building a stone fabrication facility that can protect workers from the levels of respirable crystalline silica contained in artificial stone can cost anywhere from $100,000 to millions for a large facility that includes an effective ventilation system, air quality monitors, a setup for wet cutting (as opposed to dry cutting, which sends dust into the air), and personal protection equipment. Ideally, an employer should also provide some form of medical surveillance on an ongoing basis to ensure that a worker’s health is being maintained.

But fabrication shops across the country are by and large not major enterprises. UCSF’s research estimates there are more than 10,000 of these businesses throughout the U.S., and Harrison estimates that more than 90 percent of them have fewer than 10 employees. “While it is possible for fabrication shops to put in that equipment, it’s really challenging. Most shops are small,” he says. “I think it’s going to be very challenging to meet the safety standards [given how] the current supply chain is organized, understanding that the manufacturers are selling to importers and distributors, which are selling slabs to small shops that are competing on the price and are going to have a really hard time putting into place and paying for all the controls necessary to protect their fabrication workers.”

There is one other plan of attack for reducing cases of silicosis: banning artificial stone altogether. Late last year, Australia announced it had passed a nationwide ban on engineered stone in an effort to reduce cases of silica-related illness. The regulation came after studies found that nearly one in four engineered-stone workers in the country had contracted silicosis. Prior to the ruling, major brands like Ikea and hardware chain Bunnings had acted quickly to remove the material from their product ranges in the region.

It’s an approach that many major stone manufacturers oppose on the basis that banning engineered stone doesn’t eliminate the only product that presents the risk of contracting silicosis—crystalline silica is also found in other commonly used materials, like concrete (albeit in smaller concentrations). Plus, they assert that the lack of regulatory efforts in Australia was behind the ban’s passage, not the inherent danger of artificial stone.

“The decision was driven by the challenges of allocating resources to control, modernize and adequately enforce regulations,” Massimo Ballucchi, vice president of institutional relations at Cosentino North America, told BOH in a statement. “The Australian government plans to create a process to assess products for exemption from this nationwide ban, and Cosentino is working with them to demonstrate further research and evidence for safely working with lower-silica products.”

Cosentino has also taken up advocating for international industry regulation and enforcement. In California, the company has supported legislation geared toward ensuring that stone fabricators comply with health and safety regulations, and it collaborated with public health and occupational safety officials on plans to implement a permanent Cal/OSHA standard for worker safety and compliance. While the state did pass temporary emergency regulations following Australia’s ban, long-term efforts have fallen short: Last month, a proposed bill called the Silicosis Prevention Act was withdrawn from consideration.

Some in the field are hopeful about the potential for safer alternatives to artificial stone. Cosentino has made major strides in that respect: Nearly a decade ago, the brand began developing a low-silica product. Today, its entire Silestone product line has low crystalline silica content (less than 40 percent), and its Silestone XM line contains less than 10 percent. Experts say it could reduce the risks of exposure.

As for this summer’s landmark case, both Cambria and Caesarstone have stated their intention to appeal the Reyes Gonzalez decision.

“Cambria will continue to defend our position, including through a comprehensive appeals process with respect to the law in these product liability cases,” read a statement the company shared with BOH. “The jury agreed in the recent California case that the worker’s injury resulted largely from the negligence and failure of his illegal employers to follow basic, well-known workplace safety rules as required by law. In this specific case, any blame to Cambria is incomprehensible where Cambria had no relationship with the workers’ employers who failed to follow any OSHA regulations and safe work practices.”

For Caesarstone, the reasoning is similar. “We believe the verdict is not supported by the facts of the case, such as its failure to acknowledge the proactive measures we’ve taken over the years to warn and educate about safe fabrication practices,” read a statement the company shared with BOH. “We believe assigning liability to responsible manufacturers like Caesarstone, rather than addressing the failures of noncompliant fabrication shops, will ultimately hinder efforts to improve industry-wide safety.”

While the specific basis of the appeal remains to be seen, Gary DiMuzio—an attorney specializing in asbestos, silica and environmental litigation—believes that an appeal based on the manufacturer’s duty (as opposed to insufficient evidence or an unfit expert) likely would not have a high chance of success according to prior case law. He cites industry practice dating back decades, which found that even manufacturers at the furthest end of a chain of distribution must not only convey warnings to end workers, but ensure they understand them. Should the manufacturers’ appeals fail, it could set a precedent with deeper consequences for the stone industry’s biggest players.

“If certain companies have caused a large number of these cases to develop, millions of dollars for each one of those cases is quite a likely scenario for a fatal illness associated with so much pain and suffering,” says DiMuzio. “I do think that there is the potential for very serious and very long-term financial harm to certain companies or industries.”

Over time, he speculates that it’s not outside the realm of possibility that designers, architects and other professionals who specify artificial stone products might also find themselves on that chain of responsibility—and potentially liable in silicosis lawsuits. Before that happens, however, DiMuzio finds it more likely that the industry undergoes “regulation through litigation”—a process that previously played out in the construction industry as builders quickly abandoned asbestos in favor of alternatives as the costs to businesses mounted.

“I think we might see that here. If companies see that they can be sued in common law courts, that they’re not just dealing with administrative fines, and that in all likelihood this isn’t going to be banned in the U.S., the litigation itself may be enough of a stick to get companies to find alternatives for this one product,” says DiMuzio.

Meanwhile, some manufacturers have already watched the cycle of rising cases and subsequent lawsuits play out abroad. In early 2023, the owner of Cosentino, Francisco Martínez-Cosentino, accepted a six-month suspended prison sentence for gross negligence after a court in the company’s home country of Spain found that the brand had inadequately labeled its high-silica stone products and caused harm to workers. As Reuters reported at the time, he accepted a plea deal, admitting liability only in the case of five stonemasons afflicted with silicosis—one of whom died while the case was still in trial. Prosecutors, however, claimed that a total of 1,856 workers in the country had been affected. Back in 2015, Caesarstone (headquartered in Israel) faced a class action lawsuit on behalf of shareholders, in part because “the extent of and risk posed by a growing number of lawsuits for approximately 60 silicosis-related injuries or deaths suffered by workers and fabricators of its product in Israel was understated.”

In most silicosis epidemics in other countries, increased awareness of the illness tended to uncover additional cases—which are often misdiagnosed by physicians unfamiliar with the disease, as it often requires a high-resolution CAT scan to detect, rather than a regular X-ray. But with lawsuits cropping up in a number of states, DiMuzio expects knowledge of the disease and discovery of cases to tick upward. Nevin also points out that the dangers of silicosis will not go away even if major manufacturers are held accountable—as long as there is demand for artificial stone, it’s likely that fabricators will continue to find sources for the material, potentially turning at some point to cheaper alternatives coming out of China, Vietnam and India. By this time next year, he expects that at least 1,000 cases will be making their way through the U.S. court system.

“If you look at how the popularity of the product increased its dominance of the market in any jurisdiction or any geography, the disease follows shortly after that, and then the litigation will follow after that,” says Nevin. “At this point, it’s growing exponentially. We’re getting about 10 new clients a week, and I’m sure there’s a lot more out there.”