Architects John Ike and Thomas A. Kligerman announced today that they are splitting up after 33 years sharing the helm of their architecture and design firm, but they don’t want to use the word divorce. After spending nearly two and a half years talking about how to recalibrate their eponymous architecture and design firm—from early “what if” musings to more complicated conversations with lawyers and bankers—the pair shared the news with their team and started calling their clients earlier this week: They would be dividing the firm into two.

Ike and Kligerman founded their firm in 1989, after working together at Robert A.M. Stern. It became Ike Kligerman Barkley with the arrival of Joel Barkley as a partner in 1999 and remained the same after Barkley’s departure in 2018. But as the two original co-founders found themselves spending more time on opposite coasts in the years that followed, they began to discuss a new chapter in their professional lives.

This is no run-of-the-mill breakup—one of those drama-filled splits where the partners can’t stand to be in the same room. Instead, the longtime partners are already joking about catching up in one another’s offices and musing on opportunities for collaboration.

The best way to describe their split might be, as Gwyneth Paltrow put it back in 2014, “conscious uncoupling.” Effective January 1, 2023, the New York–based firm Kligerman Architecture & Design will be led by Kligerman, Joe Carline, Andrew Davis, Margie Lavender and Ross Padluck as partners, along with Alex Eng as director of design. Ike Baker Velten, based in Oakland, California, will be led by Ike, Carl Baker and Tyler Velten.

Ahead of the announcement, BOH caught up with the pair to discuss their new paths and partners, the secret to a strong partnership and why their legacies will always be inextricably linked.

Did either of you feel like you had an existing road map to navigate this shift?

Kligerman: I’m not sure we’ve seen a model for this, but we’ve certainly seen examples of what we have never wanted. We’ve seen more what can go wrong, where there’s this acrimonious divorce. But this is an amicable opportunity for each of us to do our own thing and be completely supportive of each other.

When did you start to get a sense that your interests were diverging?

Kligerman: 1974? I’m joking. I don’t know, John, what would you say?

Ike: I would say when Joel [Barkley] left in 2018.

And you started to reimagine the way you wanted to work?

Kligerman: I don’t think we thought of that immediately. What we did immediately was sort of right the ship—talking to our clients, taking over jobs, things like that. As we began to work on these projects, we started conversations—probably in 2019—and we sort of thought, Maybe we should really do our own thing. John was spending more time out West and I was not spending as much time out West, and it just evolved that way. But I don’t think there was one day where we said, “That’s it.”

Ike: It was an evolutionary process. The fact is that this is not a huge departure from the way we’ve always operated. We share administrative and infrastructural resources, and have really relied on each other for advice and design critiques, but we’ve [otherwise] operated very independently for most of our partnership.

So the creative process doesn’t really change.

Kligerman: In a way, nothing is changing. The name is changing, we have new partners, and there’s some legal stuff that no one else really has to care about. But in terms of the day-to-day for our clients, vendors, contractors, interior designers, landscape architects—there’s really no change. [Landscape architect] Ed Hollander already calls me for my jobs and calls John for his. So moment to moment, other than the logo, nothing’s different.

You mentioned your new partners. How did those relationships evolve?

Ike: There are people who really demonstrated that they were leaders. And this is just a recognition of their roles, really.

Kligerman: I totally agree. And as I’ve gotten a little older, it’s nice to look back over 33 years, but you begin to look forward in a different way than you did 25 years ago. I never want to retire, and I don’t want my clients to think I’m going to get distracted, but I wouldn’t mind slowing down a little bit or doing other things. So as we’re thinking about how the firm continues, it’s also about what’s fair for the leadership team under us that, in some cases, has been here for 20-some years. We have always developed our team from within, so it seemed not only fair, but also practical, and like the right thing to do by the others in the firm.

Do new partners change the creative process?

Kligerman: I am excited about sharing the burden of things that John and I took the lead on, like getting new clients, job development and strategy—you know, the big-picture stuff. I’d love to involve other people, not just in the day-to-day work and the nuts and bolts of getting a house built, and it has been exciting seeing these new partners stepping up. One of mine just got a great new project, a big apartment overlooking Riverside Drive and the Hudson, and another one’s getting something in Rhode Island, and that’s great to see. If you’re not a partner, you don't think about things in the same way, and making partner has really changed their outlook and their energy. I think it’s been energizing for everyone.

How do you divide your shared administrative support system between the two firms?

Kligerman: That’s one of the things we had to really untangle. We were running it as one firm when actually legally it was two firms. And even though we had two offices, all the invoicing, billing, bank accounts and most of that staff was in New York—so we had to go back a number of years and undo some financial stuff.

Ike: Our CFO and longtime bookkeeper both stayed in New York, so we just hired someone [in Oakland] who is going to wear a couple of hats, both in marketing and as an administrative head, and then we have a bookkeeping service. The staff size in Oakland will be 10 people versus 40 or more in New York, so it made more sense to start a new administrative support system in Oakland.

Do you see the firm in Oakland growing to be as large as the New York firm

Ike: Probably not. It’ll probably grow some, but I think a more accurate target would be 15 and 20. We’re just trying to maintain the quality and the process. I’m really lucky with my new partners, Tyler and Carl, in that they’re both excellent designers, and good administrators and project managers. It’s very similar to the way Tom, Joel and I were—we’re always design first, and we were all equally strong designers, but we had different approaches. But it has always—always—been about design and architecture.

Kligerman: I think what’s paramount is the conversation, before anything—before money or legal or marketing, it’s always about the design. If you maintain that, everything else will flow.

How did you think about the growth of your business over the years?

Kligerman: I think early on John was much looser about it than I was. He was like, “The firm will grow as it needs to,” [whereas] I always had this goal of 50 people. A number of people had advised us that the [same] backup you need [to support] a team of 30 people could actually run it for a team of 50, so that was always the number in the back of my head. I think we’re at 45 people right now between the two firms, but we didn’t do anything specifically to get to that number beyond keeping ourselves out in front of the design world and the potential client world.

Can you walk me through what has surprised you in the process of untethering from each other?

Kligerman: We’ve talked about trying to keep our audience—whoever that is, including our clients—from being confused. If John’s on the West Coast more than the East Coast, who do his former East Coast clients call? And vice versa. So we have an agreement on how we handle incoming inquiries about jobs: Was it one of John’s former clients? Is it a new client who saw something of John’s? That’s been one of the things we’ve really worked on.

I’d imagine it’s got to be some combination of what makes sense for the client, what plays to each of your strengths and what feels most fair.

Kligerman: Yes—especially what’s fair. Because what you don’t want to do is to get along for three decades as a firm, and then the firm splits amicably, and then you get into a spat about a new project that comes in. We wanted to be clear about that stuff.

I can give you an example: We are each putting out a book—mine comes out in October [with Monacelli Press] and John’s comes out in the spring [through Vendome Press]. I got a call from someone on the West Coast who said, “Do you want to do a book launch in San Francisco?” Which I’d love to do, but is that going to be confusing that the firms are separating, but then here’s Tom selling his book on the West Coast? So it’s that kind of thing you end up having to talk about.

Where did you land on that?

Ike: He should absolutely go sell his book on the West Coast.

Kligerman: Yeah. But instead of just doing it, we had a conversation about it so that John didn’t wake up one morning and see in his email, “Come and hear Tom’s book.”

Do you imagine that your careers will still remain linked in some ways as you move forward separately?

Ike: I think people will tend to think of us as coming from similar approaches. It’s not like one of us is a really strong modernist and the other is more of a traditionalist. We are on the same wavelength with regard to those things, and I think our legacies will probably be linked.

Kligerman: On a related note, we’ve talked a lot about the staff, because the staff in New York are really good friends—not just professionally, but [they] also have real friendships with one another and with the team on the West Coast. Sometimes they’re in that office, and sometimes those people are here. So we’ve encouraged everybody to stay in touch and be friends, but we’ve also talked about the fact that there might be a time when there’s some project in New York that John’s working on and we could do some of the work for it and vice versa. I think John’s right that the public perception will always link us, but there’s also an opportunity for us to help each other out.

What do you see coming next for the two of you as friends and former partners?

Kligerman: We’ve joked about John coming by and having a beer or parking in the office in Oakland to make phone calls. We literally talked about it yesterday.

Ike: I think that it will continue. I mean, we met each other in school—I was in graduate school, Tom was an undergraduate [at Columbia University]—and then we worked together, and we just get along. It’s easy. I think that, as with any relationship, being honest with each other is really what has helped keep it going and proceed into the future.

How did you know you would be good partners back when you launched the firm?

Kligerman: We worked on some of the same projects together in California, and then we each had our own projects in New Jersey and we would sometimes ride down together and ride back. We just got along. I don’t know if everybody thinks about starting their own firm, but I would look around the office and think, “Who would I want to work with?” And the only one I really came up with was John.

In your experience, what is the secret to getting partnerships right?

Ike: I’m certainly not the best communicator, and my wife will tell you that as well, but I think you do have to communicate, and then be able to give and take. Typically, if one of us has an idea—even if we may not share the same interest—we’ve always encouraged each other to go for it. Allowing personal growth within the relationship is super important.

Kligerman: I think we had a shared worldview in everything from politics to history, from travel to food, and certainly in architecture and interiors. So the big picture we agreed on, but it didn’t mean we were in lockstep all the time. One of the great things I learned from John was to live and let live. If John wanted to go to Iceland to look at Icelandic architecture, fine. If I wanted to work with the Sir John Soane’s Museum, fine. Like any good relationship, there was a broad shared view and lots of freedom to do what you want to do. And for the [work] questions, whether it was about a client relationship or a floor plan or materials, you could trust you’d get a good answer. It may not always be the right answer, but it was an answer you knew you could hang your hat on. So it was both being tied and also being untied that worked well.

What do you see as the legacies of your firms, together and separately, and what are you excited for as you look ahead?

Ike: We’re rooted in a process where we use history as a departure point but applied in a synthetic way to different sites and contexts, and then we innovate. Tom has been really stretching the boundaries of what you can do with wood as a skin for a building. I don’t have a focus in that way, but each project is always a synthesis of multiple sources and trying to create an interesting and innovative design solution, while incorporating materials and landscape in a holistic way.

Kligerman: To build on that, I have more ideas now than I’ve ever had. Maybe that’s just because you become more facile over time—you can do things with more ease, and you don’t struggle with the basics of architecture the way you did early in your career. It’s almost like subconsciously your hand knows how to take care of a lot of it, freeing up your mind to do new things. So I look forward to a firm that really goes forward and backward. As John says, we’re always rooted in history and context and culture, but our modern direction will become more modern, and the traditional things will become more traditional. It’s not that we’re bifurcating—we’re stretching the boundaries of the kind of buildings we do, and everything in between. I think people might see work that is more daring and innovative.

I guess the big hope is that 100 years from now, someone will open the books on our houses and get inspiration the same way we open a book from one of the greats, that we become in some way a milestone in the development of American residential architecture. [In which case] we’re not thinking about the firm that ends when we retire but about the firm in the broader context of the canon of American architecture—that’s the real inspiration.

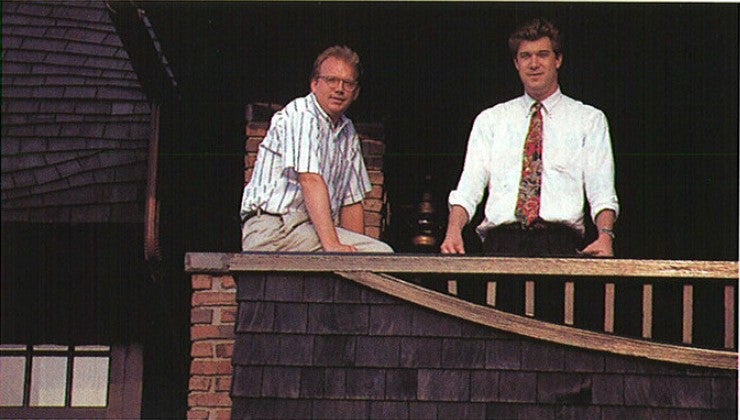

Homepage image: Ike and Kligerman on a balcony during the early stages of their partnership in 1993 | Courtesy of Norman Mcgrath