In House Beautiful, it always feels as if it’s one o’clock on a Saturday afternoon. Veranda happens just before the golden hour, around four. Architectural Digest takes place at high noon.

Flip through the pages of shelter magazines (or scroll through your Instagram feed) and you’ll notice something so ubiquitous it’s rarely questioned: The overwhelming majority of design photography depicts rooms during the day. It’s as though all interior design happens in one of those far-north Scandinavian countries in the heart of summer, when darkness only falls for a few short hours.

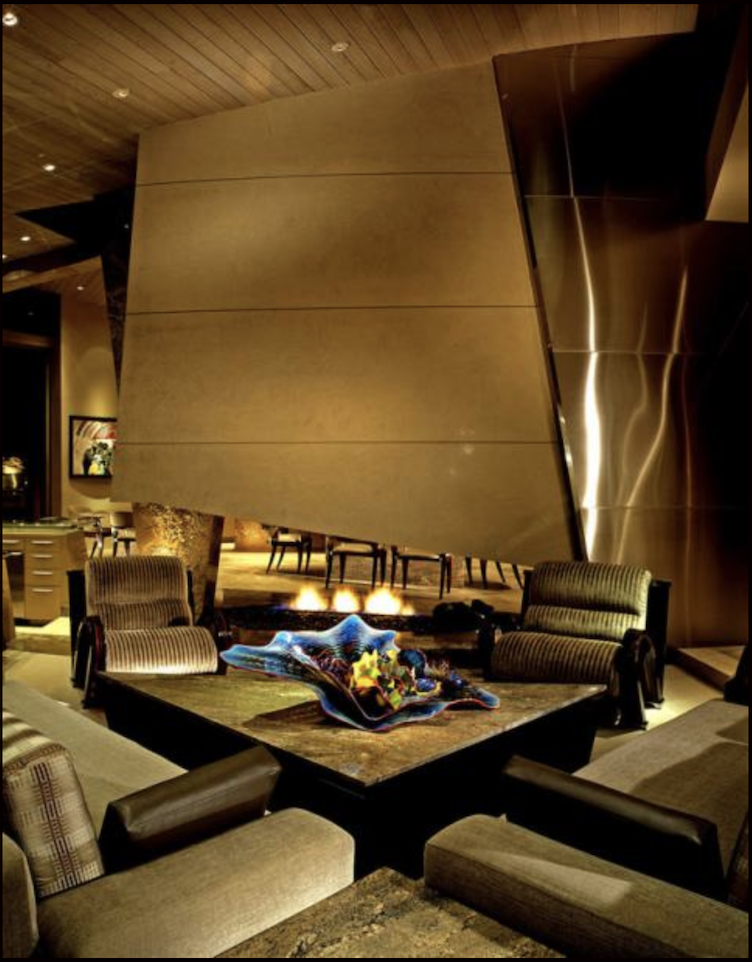

It hasn’t always been this way. Open up a dusty copy of Architectural Digest from the 1970s and you’ll see crackling fireplaces, blue skylines at dusk, glowing sconces, pinpoint lighting and rooms bathed in yellow light. But as the 1980s drew to a close, nighttime interiors began to slowly disappear from shelter magazines. By the turn of the century, they had vanished almost entirely.

Who killed the nighttime?

After talking to designers, photographers, editors, photo directors and one legend, Business of Home can conclusively report: No one really knows. But we can present a few theories of the case.

THE PAIGE RENSE THEORY

What’s normal now is actually the true historical oddity—for much of the 20th century, shelter magazines published photographs of rooms at night. Still, the heyday of nighttime shooting was undeniably the 1970s and ’80s—specifically, the 1970s and ’80s found in the pages of Architectural Digest. When asked who made nighttime interiors popular, many answer with a single name: Paige Rense, the legendary editor who lifted the magazine out of obscurity and transformed it into a cultural force.

“Architectural Digest was the bible,” says photographer Eric Piasecki. “If you wanted to be a successful interior photographer, you emulated what AD was doing. [Shooting at night] was just what Paige Rense liked, so people did that.”

Intriguingly however, Rense herself passes most of the credit to the photographers she worked with. “It was the photographer’s choice, not mine,” she tells Business of Home. “There wasn’t any one person, including me.”

Rense was a protector and patron of her photographers. Famously, there were no editors and stylists allowed on shoots for AD; instead, the final product was always a pure collaboration between the designer and the photographer. The talents of the era returned the trust, giving Rense their finest work. And it just so happened that one of her favorite photographers specialized in shooting at night.

“No one could do it better than Jaime Ardiles-Arce,” says James Huntington, Rense’s longtime photo director. “He was the absolute master of nighttime photography.” Ardiles-Arce’s photographs from the era are often dramatic, theatrical productions that evoke the glamour of a city at night. “That was [his] look and Paige Rense happened to love it,” says Peter Vitale, another photographer who worked with AD during the period. “I think [the focus on nighttime shooting] happened somewhat accidentally. She just loved his work and wanted it to continue.”

It’s a chicken-and-egg problem. Was it Rense’s taste, or her photographers’ talents that drove the look? Whatever the cause, the effect was clear: Two decades cloaked under cover of night. “It was a time for dramatic furniture,” says Adèle Cygelman, an editor who worked for Architectural Digest throughout the 1980s and ’90s. “You had a lot of black leather couches and red lacquered tables, and that stuff looks best at night.”

Designers and firms like Jay Spectre, Hendrix/Allardyce, Loyd-Paxton and Steve Chase defined the era—their opulent creations captured at night by photographers like Ardiles-Arce, Vitale, Steven Brooke, Mary Nichols and Derry Moore. Nichols recalls a feeling of camaraderie at the magazine and an unerring vision at the top. “You’d hear, ‘Paige feels this looks wonderful at night but she would like a few daylight shots,’” she says. “She always had an opinion, and you’d always agree with her when you saw the project. She never directed our shoots, but if she accepted [a project], she had seen it herself.”

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, photographers began to notice fewer requests for nighttime shots coming from AD. Rense is once again quick to credit her photographers—and her photographers are just as quick to pass the credit right back. “I think it went along with all of the changes in design,” says Nichols. “All of a sudden, [Rense] got tired of showing all the blue-chip art collections in the flats of Beverly Hills—it was all the same curators and all sampled the same art and it got shown too often. That’s what happened with dusk shots. They were shown too often.”

Which brings up an intriguing possibility: Perhaps nighttime interior photography disappeared simply because Paige Rense—or maybe her favorite photographers—got tired of it.

THE MARTHA STEWART THEORY

Just as Rense’s Architectural Digest defined the culture of the home in the ’70s and ’80s, Martha Stewart owned the ’90s. The New Jersey–born former stockbroker had written several successful books on entertaining in the decade prior, but it wasn’t until 1990 that her TV show (and magazine of the same name), Martha Stewart Living, catapulted her to ubiquity. In 1995, New York magazine declared her “the definitive American woman of our time.”

Martha Stewart Living wasn’t purely an interior design magazine, but Stewart’s conception of the home—wholesome, rural, traditional—became the dominant vision of the era. Home was a place where turkeys were thoroughly basted, cookies were fresh baked, and dogs were well trained. Needless to say, this particular ideal lent itself more to an afternoon in Greenwich than it did to an evening on the Lower East Side.

“The ’70s and ’80s were a different time,” says Cygelman. “It was a disco era, where people were cocooning and doing things behind heavy drapes. People stopped living like that in the ’90s.” To be sure, changes like these are the result of broad cultural forces (one designer we spoke with drew a connection between the heteronormative “Martha Stewart Land” of the ’90s and the death of a generation of gay creatives from the AIDS crisis), rather than the actions or aesthetic of a single person. But still, no single person exemplifies the shift better than Stewart, and no single person had more influence on the home.

Where Martha went, so did others: Her rise coincided with the widespread decline of nighttime interiors. “New editors came into the picture and they wanted to make an impact in terms of changing the look,” says Vitale. “There was Martha Stewart Living, and Veranda was coming up—they were all about the South, and the outdoors and they started pushing daytime and it just took over.”

THE BUDGET THEORY

Shooting at night is expensive, full stop. It requires expensive lighting equipment, and it takes longer than shooting during the day. “We used to travel around with 28 cases of equipment in a massive van,” says Piasecki, recalling the early days of his apprenticeship to Florida photographer Dan Forer, who specialized in nighttime shoots. “Every shot took four or five hours to set up, and sometimes it would take four nights for the entire shoot.”

Even during the comparably flush days of publishing, there was pressure from executives to keep costs down on photo shoots. Rense recalls that, for the first decade of her tenure at AD, she was mostly using photographs that had been independently taken by designers and photographers then submitted to the magazine. As AD took off in the 1980s and she began commissioning shoots, she got pushback from upstairs.

“When we started doing this magazine, our budget was pretty much nothing,” she says. “As the magazine became more and more popular, I went to [an executive at Knapp, the magazine’s ownership at the time] and said, ‘There has to be a change; I have to give photographers proper payment for their work.’ He said, ‘You pay them?’”

As print circulation and ad revenue has declined since the heyday of the 1990s, the situation has certainly not improved. With one eye on their balance sheets, magazines began finding it harder to justify expensive multiday—and multinight—shoots. “What used to be a four-day shoot became a three-day shoot, what used to be a three-day shoot became a two-day shoot,” says Sophie Donelson, former editor in chief of House Beautiful. “You don’t have the resources to take risks anymore, you really need a sure-thing project and a sure-thing photographer.”

It may have been a change in fashion that led to the demise of nighttime shooting, but financial pressure has surely played a role in keeping it firmly in the past.

THE VANISHING CRAFT THEORY

Though photography is taught in schools, real-world education in the field still operates largely on the apprenticeship model. Beginners work as assistants for experts, and the tools of the craft are passed down from generation to generation. As nighttime shooting fell out of fashion in the 1990s, interior photographers stopped doing it—and their apprentices stopped learning it.

“The artistry of it has been a bit lost,” says Piasecki. “Dan actually had a background in theatrical lighting, and it was a very complicated technique. You’d do these really long exposures, and every shot was a drawn-out process.”

As digital technology began to transform the craft, the techniques behind nighttime photography slipped even farther away. Most photographers now spend far more time learning how to manipulate an image in Photoshop after the fact than how to light a shot before it's taken. “Newer photographers who only know the digital age of correcting after the shoot simply never use lighting,” says Nichols. Piasecki concurs, adding that homeowners are often amused when photographers start a shoot by turning off every light in the house.

This confluence of factors has created a vacuum of high-profile photographers who shoot at night, limiting options for adventurous editors who might consider commissioning an evening shot. “I don’t think there are many contemporary photographers at the top of their field [who shoot at night],” says Donelson. “So if you go into it, you risk it not turning out all that well.”

The way photography is distributed now surely plays a role as well. Most of us see interiors as tiny squares madly scrolling under our thumbs at breakneck speed. Brightness and color jump out and catch our attention—we no longer have the patience to slow down and peer into a dark room.

THE TASTE THEORY

This is perhaps the simplest, broadest explanation—and likely the most accurate: We stopped shooting interiors at night because it fell out of fashion. The look became so strongly associated with 1970s and ’80s that nighttime interiors feel inherently dated. Even hospitality clients, long a source of work for nighttime photo specialists, have pulled back. “In the past five years, hotels and restaurants haven’t wanted night shoots,” says Vitale. “Everyone prefers the day.”

However, most things that cycle out of style tend to cycle back in—nighttime hasn’t. And while it’s understandable that a certain look can come and go, it’s odd that we’ve lost an entire 12 hours of the day to fashion. “Most of us use our home mostly in the evening. We work, and when we get home we only enjoy a few hours of daylight before we’re in our homes at night—but people still decorate for the daytime,” says Donelson. “We’ve become so trained to equate natural light with beauty—and it really does make you feel good. But that idea of warmth and intimacy, a cozier space—the way an evening can feel—has equal resonance on the psyche. … Our trade just hasn’t put forward a good vision of what living well at night looks like.”

GONE FOR GOOD?

Most of the sources we spoke to tended to agree: Nighttime photography isn’t coming back anytime soon. But fashion always seems absolute—until it changes. And some, like New York–based designer Alex P. White, are pushing for a return to the slinky glamour of nighttime interiors.

White recently designed a model apartment at 196 Orchard, a new building on the Lower East Side, with the theatrical nighttime glamour of the early 1980s in mind—and he styled it specifically to photograph well at night. “It’s a classic New York apartment where the windows look into the interior, so it’s always sort of twilight,” he says. “It needs to be as moody as possible, and dramatic lighting is what’s going to maximize that.”

White’s predilection for nighttime shooting comes partially from a childhood obsession with the “adult” culture of his 1980s youth. It’s also, he says, a pushback to the ubiquitous daytime look. “I think there’s this documentarian aspect to interior photography now—‘Let’s capture this in natural light as though you were turning the corner in the morning to get your morning coffee.’ However, we know that has its own kind of staging and theatricality,” he says. “I’m so sick of everything looking so blown out and white and neutralized.”

White has taken to shooting all of his projects at both daytime and nighttime, and has been posting images of his favorite ’70s and ’80s night shots to his Instagram feed: “It’s kind of a call to arms—why aren’t we doing this?” If it works, and the night does come swinging back, he’ll be thrilled. Some photographers may not be.

“To a degree, maybe it will come back,” says Vitale. “But I hope not. I hated shooting at night. I always wanted a margarita at seven o’clock but I couldn’t—I was just getting to work.”

Homepage photo: Peter Vitale