The other night, I did the thing you’re absolutely, positively not supposed to do: I shopped a designer.

Reader, forgive me. I had permission. Over the past year, I’ve become increasingly impressed by how good visual search technology has gotten, and I wanted to put it to the test. San Francisco designer Noz Nozawa graciously agreed to be the guinea pig in a simple experiment: We would look at pictures from her portfolio, scan them with Google’s visual search tool, Lens, and see if the algorithm could accurately identify the furniture and decor. Bonus points if it coughed up a shoppable link.

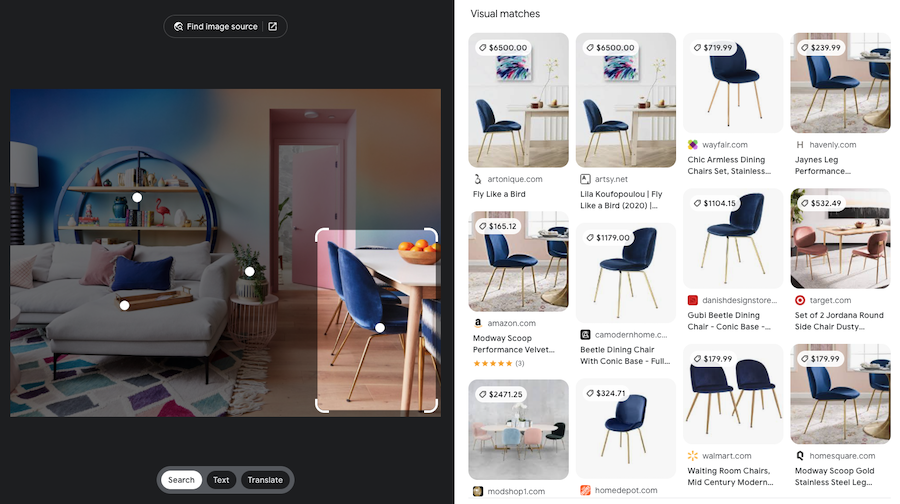

We started off with a vibe-y, rainbow-hued living room Nozawa had designed early in her career. Unlike a simple reverse image search, Lens allows you to isolate individual details from a picture—in this case, I started with what I thought would be a challenge for the algorithm, a chunky blue lamp in the corner of the photo, halfway cropped out of the frame. I clicked, Google thought for a quick second, then produced a dozen or so options.

“That’s it,” Nozawa said, indicating a link for a lamp from Coastal Living, retail price $1,050. “This is really good!”

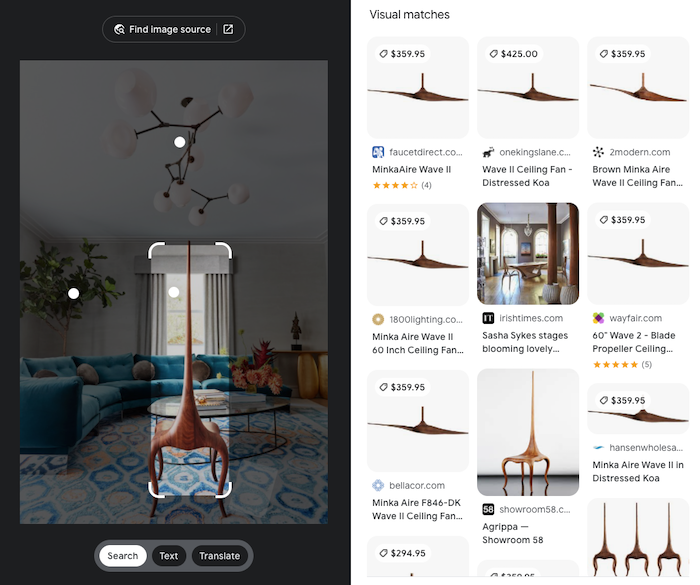

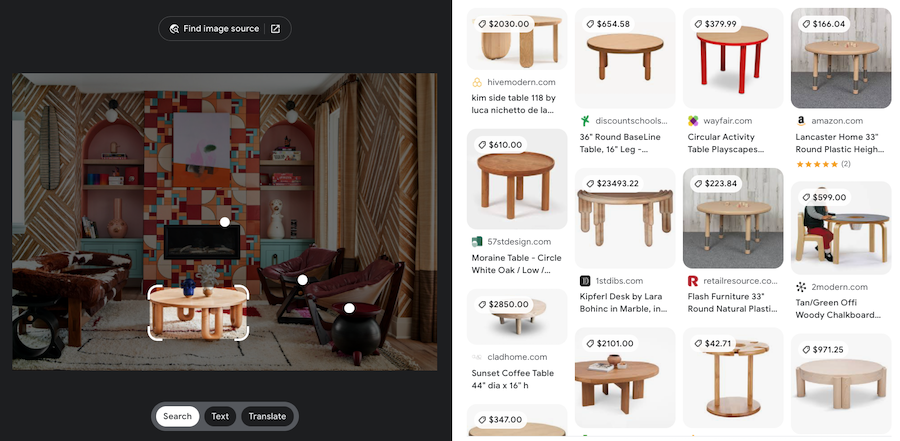

We moved on. Lens missed on a Hem side table but was able to quickly identify an accessories tray from West Elm and a pair of Gubi beetle chairs in blue velvet. Elsewhere, the results were similar. Throughout Nozawa’s projects, the algorithm accurately IDed a table from Kifu, a stool and a vase by designer Jomo Tariku, the Lady Sting chair by Agrippa and a chandelier from Ochre.

Lens wasn’t perfect. For custom pieces, like a circular étagère Nozawa had commissioned and powder-coated in rich blue, it could only suggest not-so-good look-alikes. It also struggled with unique vintage items and, surprisingly, with wallpaper and rugs. Sofas, too, were a challenge. But even there, Lens sometimes came through. In the rainbow-y living room, at first it offered up a handful of suggestions for the sofa—all wrong.

“These aren’t right,” Nozawa said, as we scrolled through. “You can tell by the fatness of the arm—that’s where the money goes on a sofa. These all have skinny arms.” Then, after scrolling through a few more options, she stopped me. “Wait! That’s it. The Jonas from DWR.”

The technology is free. The interface is simple. In a few clicks, we were able to fairly accurately identify at least half of the objects in a room. “Honestly, if this means I don’t have to answer Instagram questions about what I used, I’m all for it,” said Nozawa with a laugh. “Those never turn into clients, anyway.”

Google Lens is not a brand-new tool. It’s been around since 2017, and the technology underpinning it—computer vision—isn’t a recent breakthrough. As early as the 1970s, scientists were training algorithms to “see” and decipher visual imagery. What has changed in the past 50 years is the sophistication of what a computer can perceive. In the beginning, it was simple shapes—a circle, for example. Now, computers can pick out a circular side table from CB2.

Computer vision may seem like exotic technology, but it’s already everywhere. If you have a newish iPhone, computer vision is what allows you to unlock it with your face. It monitors traffic and analyzes X-rays and is in everything from high-end military-grade surveillance to simple day-to-day internet usage: When a CAPTCHA login prompts you to prove you’re a human by clicking on every little square with a traffic sign, you’re helping teach a computer to recognize traffic signs.

Computer vision has also found its way into shopping, largely through a suite of technologies collectively known as visual search. Behind the curtain, the technology is complex. Using it is simple. As I did with Nozawa, you just point your phone’s camera at something you like (or scan an image online), and it returns data—most often shoppable links to similar products.

The promise of visual search, say evangelists, is to break free from our habit of hacking away at Google with clunky search terms like “Instagram famous mirror curvy pink” and simply show computers exactly what we want. “We’ve almost learned how to speak in the language of the machines, so they can get us to the information we want,” says Clark Boyd, the director of strategy for home-focused AI visual search startup Cadeera. “You would never speak out loud the way you search on Google. But we’ve shoved our language into their algorithm.”

In recent years, major retailers—especially in fashion—have all embraced visual search as a way to draw customers into their orbit. (The premise: Show us sneakers you like, and we’ll show you our version, along with an outfit that matches!) The same is true for the tech giants. Amazon is investing deeply in visual search, as is Meta. So, too, is Pinterest, which has a functionality not unlike Google Lens.

At this point, says Boyd, accurately identifying objects (read: products) in a photo is “table stakes.” The next step is for tech platforms to move beyond simply telling users what’s in a photo and what they can do with it. For that, “multimodal” visual search is a significant nut to be cracked—it’s a process in which users combine an image with a text or voice query. Imagine, for example, pointing your smartphone at a sofa and saying, “I want one like that, but in leather, and with a more modern silhouette,” and getting a shoppable list of results.

“The next frontier is context,” says Boyd. “People don’t really want identification all the time. They want more inspiration, more information. They’re in an open mindset. ‘Here’s a starter, I’m interested in this picture, but tell me more.’”

Despite all the investment and technological leaps forward, I haven’t seen a ton of evidence that visual search has made a big impact on the design industry (yet). I asked a handful of publicists to reach out to their clients and see if they were familiar with Google Lens—crickets. That reaction mirrored my own anecdotal experience. Whether it’s designers, makers or industry professionals, people either aren’t using or aren’t talking about this technology. It’s a magic trick hiding in plain sight.

(The exception would be antiques dealers. The Instagram-famous vintage picker and memelord known pseudonymously as Herman Wakefield told me that Google Lens was a standard tool in his profession, mostly used to roughly identify pieces found at estate sales or thrift stores. “Everyone uses it now, but nobody says they do,” he wrote via Instagram DM. “Because they all think they’re the only ones that know about it.”)

Visual search’s seeming invisibility is strange, because the technology could have profound consequences for the design industry. A world where clients routinely wave their phone at a room, or click on an image of one, and instantly discover where everything came from (and, potentially, how much it costs) is different from the one we live in today.

How it would affect individual designers depends on the designer. It could push some toward relying on custom sources or unique vintage pieces, which elude scanning by visual search. It could also lead some to moving away from a pricing model that favors markups on product, which might come under greater scrutiny.

Another potential consequence of ubiquitous, near-perfect visual search: Tech platforms will sell against designers’ work. To some extent, this is already happening. Pinterest uses a visual search algorithm that allows users to scan some images for look-alike products and shop. Instagram and Facebook have been experimenting with similar functionality.

This exact move—using designers’ work to sell product—is precisely what got Houzz in hot water among designers in 2018. Over time, Houzz showed signs of accommodation, geofencing off certain users from being able to “shop” a designers’ photos and eventually allowing designers to opt out of photo tagging.

In retrospect, such accommodations almost seem quaint. Any one platform may seek to protect its creators’ content. But if a user can simply right-click on an image and use Google Lens to scan it for product, such defenses are ultimately only cosmetic. Over time, pressure to monetize will likely lead platforms to tag and sell against the content of its creators. The main question is not if, but when, how and whether designers will get a cut.

“Instagram will take the lead on that,” says Boyd. “I’m sure you’ve seen that Meta’s share price has taken a hit recently. Lots of things going on are damaging them, and so they really want to pin down commerce opportunities within their apps to stop people leaving and shopping elsewhere.”

To be fair, the design industry is not entirely blind to this coming change. In recent weeks, I’ve seen tutorials pop up on LinkedIn advising designers to start posting their projects as videos to evade detection by visual search. If your only goal is to dodge the algorithms, it’s a legitimate strategy—they have a much harder time scanning video than still imagery. But it won’t work forever. Boyd says that tech platforms are working at a breakneck pace to create visual search technology that performs as well on videos as it does on still images. It’s not going to happen overnight, but it’s a solvable challenge—one he suggests will take a few years, not a few decades.

You can pivot to a different format. But over time, the algorithm is going to catch up.

Will visual search disrupt the design industry as we know it? I find it hard to imagine it will have no impact (one guess: It will lead more consumers to knockoff furniture). But after spending some time with the technology, I’m also not convinced it’s a real threat to designers.

For example, my test with Noz Nozawa: While it produced some shockingly accurate results, it was an imperfect experiment. Nozawa pointed this out to me as we were going through her portfolio. “The thing is, I know what I’m looking for. I know which pieces I picked for these rooms,” she said. “You should try this with someone who has no idea what I did and see if they’re able to figure it out.”

She was right. Visual search algorithms are powerful, but they’re only so precise. They can scan a chair and show a user a bunch of other chairs that look similar. Sometimes, the match is obvious, but in many cases, it’s not.

Take the pair of Gubi chairs that Google Lens was able to pick out from Nozawa’s project. The algorithm suggested not only the originals, available for sale through an authorized dealer, but also a huge range of near-identical knockoffs from Wayfair and Amazon (one undeniable revelation of visual search is that the market is completely saturated with copycat furniture). Some of the knockoffs cost as little as $165, others as much as $719. Seen through the flattening lens of e-commerce, they all looked more or less the same. An average consumer would find it extremely difficult to know which to buy and what real difference there was between a $165 and a $1,000 chair.

Making those choices for other products is even more complicated. Google Lens could occasionally identify similar wallpaper patterns, but without Nozawa’s input, it was difficult for me to suss out whether I had found an exact match. Even if I had, truth be told, I still would have been clueless about how much to order, who to call to install it or whether I was getting a good price. In other words: I would have needed a designer.

After using Google Lens for a bit, I became convinced that the genuinely endangered professionals were not interior designers at all, but design editors who write “shop the look”–type articles. If you’re looking to find an affordable, easily shoppable version of something you see in Architectural Digest, Google Lens is pretty darn good. If you want an identical match, it’s not always quite as easy.

Visual search, too, has its own challenges to overcome. While the technology can often come across as miraculous on first use, it has struggled to find a regular place in most users’ lives. The truth is, most of us aren’t wandering through our days looking to identify sofas we encounter. That may change in the coming years, says Boyd, but for now, visual search suffers from a “stickiness” problem: “It can be a bit of a party trick. People will say, ‘That’s amazing! I’ve never seen anything like it!’ And then they never use it again.”

But even if visual search were a perfect, ubiquitous technology, I still don’t think most designers should panic. Putting together a beautiful home is a lot more complicated than simply knowing where to buy a particular lamp. And designers who obsess over guarding their past work may risk losing focus on the future.

“The thing that makes you who you are as a designer is your brain, it’s not the stuff you found,” Nozawa stated. “Even if I tell someone exactly what’s in this room—and often I have to do that to get published in a magazine anyway—then what? You could copy this exactly, but so what? I’m already on to the next project.”

Homepage photo: A San Francisco living room by Noz Nozawa | Courtesy of Noz Design