In 2020, Ikea made headlines when it reached a $46 million settlement with the family of a toddler killed by the tip-over of an unsecured dresser. It was a tragic news story, and it had huge business consequences: Soon after, Ikea began requiring customers to sign a form acknowledging risk whenever they purchased a heavy piece of furniture. Though it made international headlines, the story was only the latest chapter in a two-decade controversy that juxtaposes gut-wrenching tragedy with the byzantine tedium of government bureaucracy. Now, a new chapter is unfolding.

Tip-over accidents are a genuine problem. The CPSC (Consumer Product Safety Commission) cites 234 fatalities resulting from tip-overs from January 2000 through April 2022, 199 of which were children. An additional 84,100 tip-over-related injuries were treated in a hospital from 2006 through 2021—and, of those, the CPSC estimates that 72 percent were injuries to children. Parent lobbying groups have long pushed for more stringent safety standards, and over the past two years, the government has actually passed legislation to make them a reality.

In September, during a rare moment of bipartisan lawmaking, the Senate passed the STURDY (Stop Tip-overs of Unstable, Risky Dressers on Youth) Act, which originally was passed by the House in June of 2021 and now awaits a final vote there. Concurrently, the CPSC revised the safety standards for free-standing chests, dressers, armoires and bureaus (items often referred to as clothing storage units, or CSUs). In October, the CPSC issued new mandatory federal safety standards for the furniture category and gave manufacturers until May 24, 2023—exactly 180 days after the original ruling—to put the new measures in place. The CPSC’s new guidelines replace the current voluntary standards, which were set forth by ASTM International (the American Society for Testing and Materials), a third-party organization that has given manufacturers an optional way to self-police their products.

To a general consumer, this might seem like a win. Safer furniture means safer kids. So, why is the furniture industry trying to stop the new rule from going into effect?

The answer is complicated, involving warring industry groups, lawsuits and at least one physics equation, but to summarize, there’s a lack of consensus on how to test products in a way that’s practical, effective and fair. One manufacturer who declined to comment for this piece deemed the issue “too political” to speak about publicly—not a response one often hears when reporting on the furniture industry. Since the CPSC published its new standard in October, the American Home Furnishings Alliance (AHFA), the trade association that represents the U.S. residential furniture industry, has filed motions to delay and even have the rule vacated, or deemed legally void.

Here, we break down the rule and why it has the furniture industry scrambling.

First, some context

To understand what has caused such a hullabaloo around the new regulations, it helps to have some understanding about the existing standards, which are entirely voluntary.

The existing ASTM standard uses two straightforward pass/fail tests. The first asks manufacturers to place an empty CSU on a hard, level, flat surface and pull out all drawers and shelves to their full extension. If the CSU falls over, the piece fails. If it remains upright, congratulations—it passes.

The second test asks manufacturers to place an empty CSU on a hard, level, flat surface and gradually apply test weight up to 50 pounds, roughly meant to account for the static weight of a 5-year-old child. For this test, only one door or drawer is open at a time, and the test weight is applied to that open feature. Each drawer or door is tested individually, and all other drawers and doors remain closed. If the CSU tips over in this configuration, it fails; if it doesn’t, it passes.

But since the program is voluntary, some products on the market never undergo such tests at all (unsurprisingly, they’re often the ones that end up being recalled). In light of such informal, inconsistent standards, it makes sense that universal furniture safety rules are finally being legislated. But that doesn’t mean implementing them is easy.

Ch-ch-changes

Most of what makes the CPSC’s new federal standard so controversial to manufacturers is how it deviates from the current ASTM standard. In a statement to Business of Home, the CPSC said that its committee on tip-overs had concluded that the stability requirements in the current standard are “not adequate to address the CSU tip-over hazard because they do not account for multiple open and filled drawers, carpeted flooring, and dynamic forces generated by children’s interactions with the CSU, such as climbing or pulling on a drawer.”

In a notoriously slow-moving industry, sometimes getting used to a major change is half the battle. In 2017, the CPSC issued an Advance Notice of Proposed Rulemaking, providing five years’ warning that changes were coming. Yet the industry was still taken off guard by what many see as a major deviation from the current standard. It seems most manufacturers were expecting something like an increase of the test weight they’d be required to use, an expectation stemming from drafts of STURDY. What the CPSC issued was, instead, a math equation.

WhAT THE new rules require

Dynamic force is at the heart of the CPSC’s case for new measures. In the organization’s view, static weight is not a useful barometer because it doesn’t reflect the way in which children actually interact with a CSU. Anyone who’s ever spent time with a toddler can tell you that kids are not pulling out a dresser drawer and then staying still—they’re trying to climb anything they can. Also, both of ASTM’s tests call for empty products, which don’t reflect real-world conditions, says the CPSC. Furthermore, limiting product testing to hard, flat surfaces fails to consider area rugs or wall-to-wall carpeting—which accounts for up to half of all flooring sold in America, by some estimates.

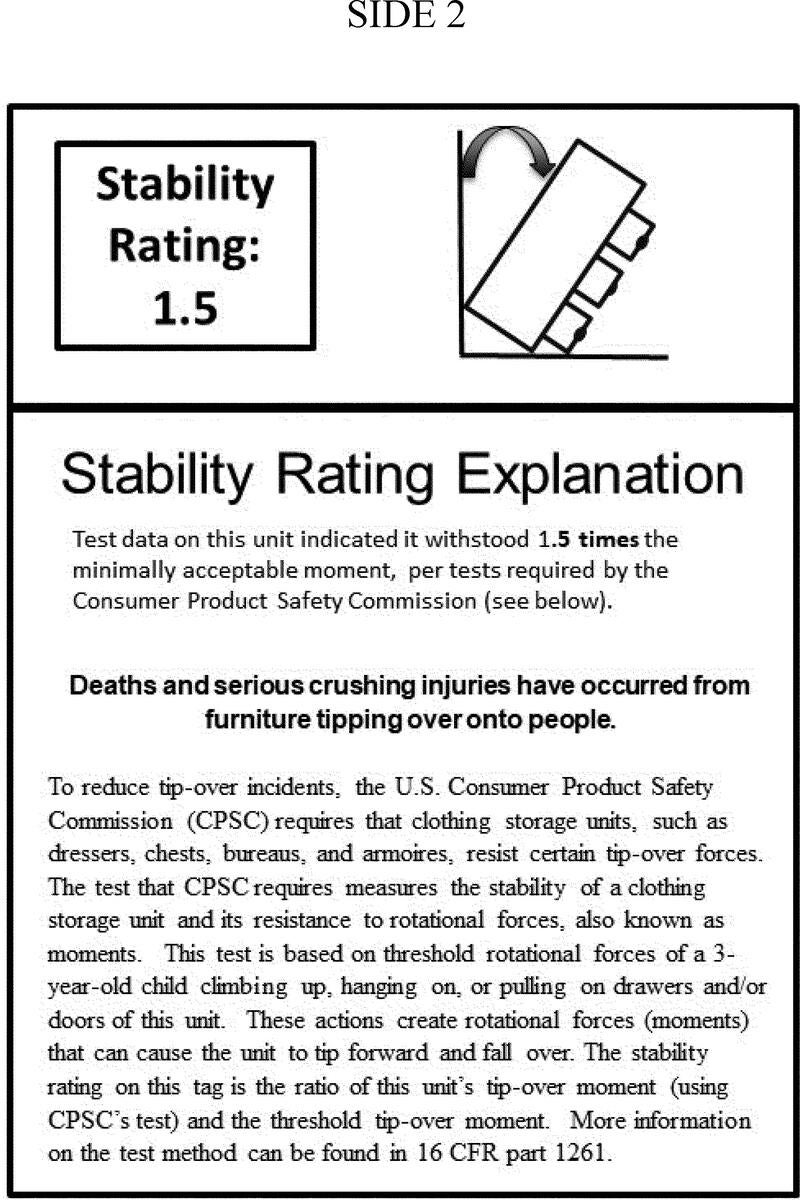

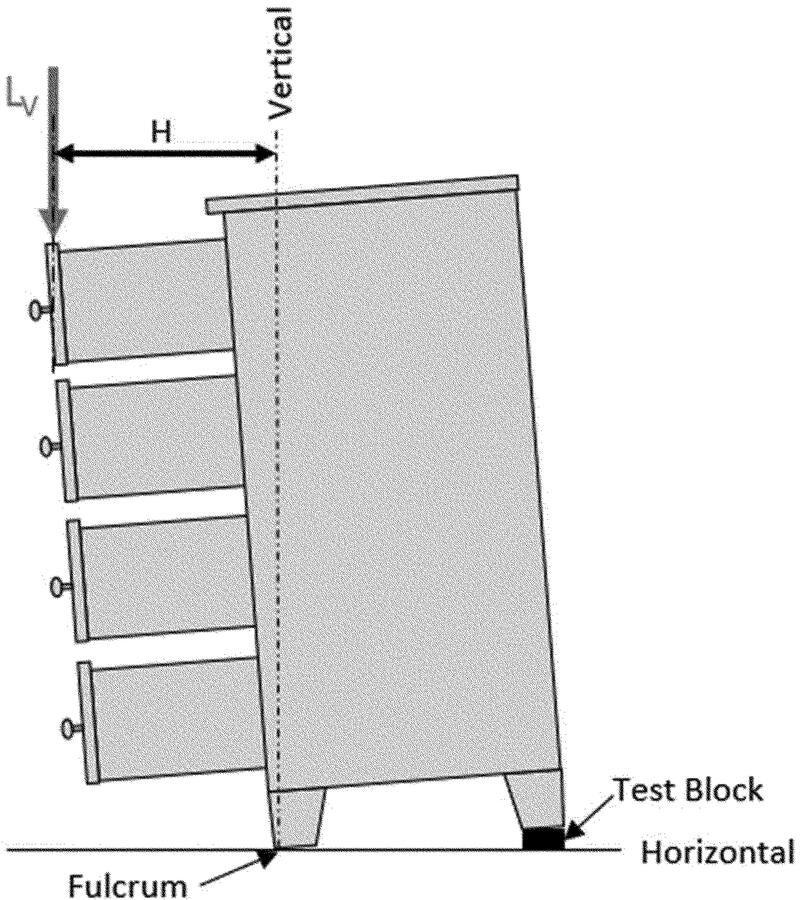

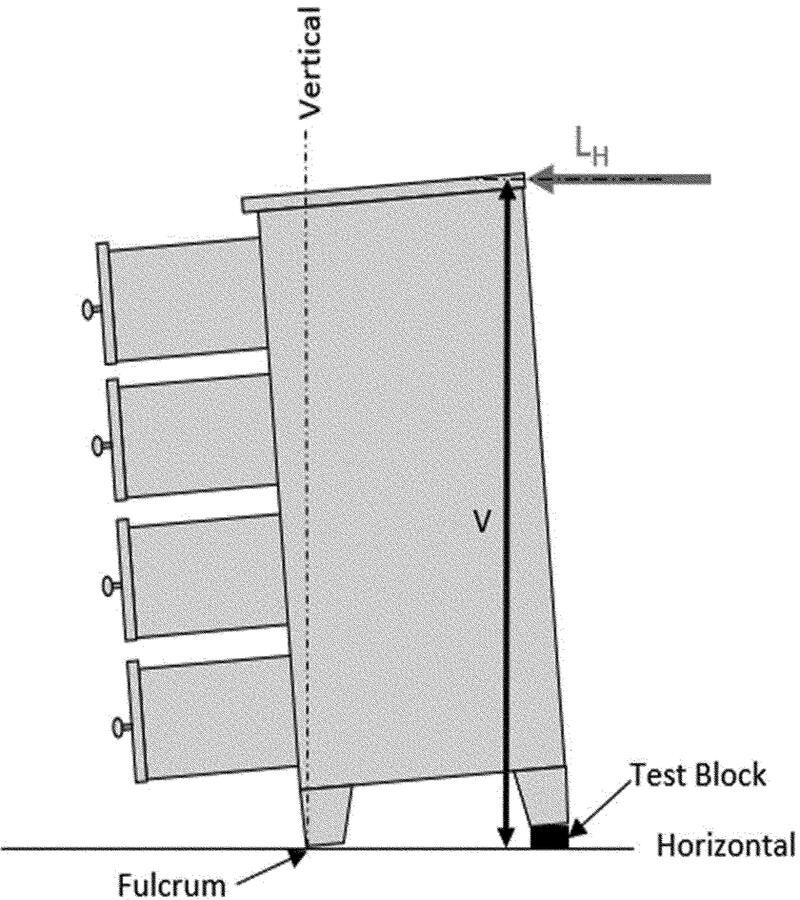

If trying to capture the real-world factors that impact furniture tip-overs sounds difficult, that’s because it is. To inform the creation of the standard, the CPSC contracted the University of Michigan Transportation Research Institute (UMTRI), an organization that primarily studies car- and traffic-related incidents, to undertake a study on children climbing CSUs. The UMTRI data is dense, unless you happen to be an engineer or spent some serious time studying physics. Amid terms like “torque,” “fulcrum,” “momentum” and “center of gravity,” the report explains there’s an instance, dubbed “the tip-over moment,” in which a certain amount of force, applied in certain ways, will cause an individual CSU to fall over. That moment, naturally, differs from piece to piece, so UMTRI created an equation for manufacturers to use during testing in order to calculate the tip-over moment.

The test requires that a CSU be angled at 1.5 degrees to simulate carpeting, with all drawers pulled out to their full extension and then filled with 8.5 pounds of volume. Then, force is applied either horizontally to the rear of the unit or vertically into the open drawers until the piece tips over. (Testers can decide which method to use.) The final instruction: “Calculate the tip-over moment of the unit by multiplying the tip-over force by the horizontal distance from the center of the force application to the fulcrum.” Slightly more involved than the current pass/fail system, you might say.

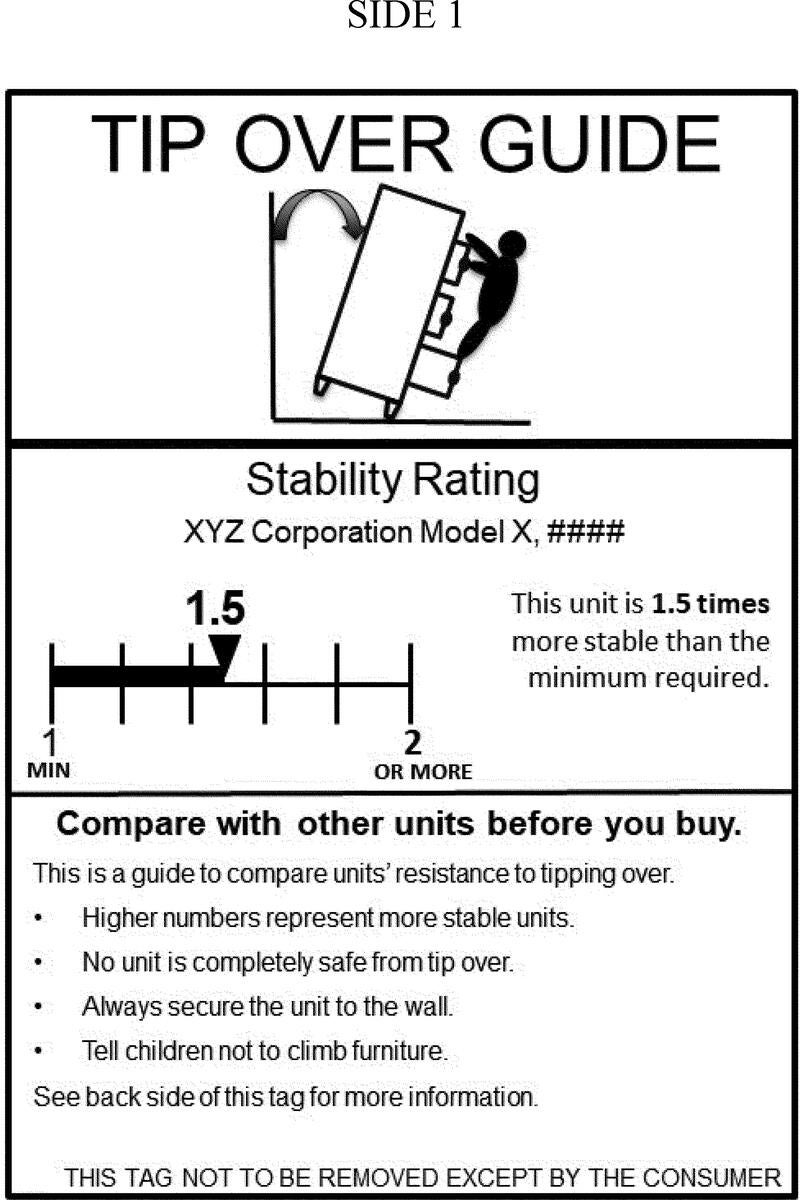

When properly administered, the test will create a numerical result and, under the new standards, pieces will receive a score on a scale of 1 to 5, ranging from least to most stable. Technically, it’s possible to score as low as 0, but those products would have failed testing and would not be allowed on the market. After the CPSC staff’s testing found that CSUs currently on the market do not exceed a stability rating of 2, even when modified to comply with the rule, the score is now listed as falling between 1 and 2 or more.

The new regulation also requires the product’s final score to be listed on a hangtag to be displayed for consumers, helping them make a more informed purchasing decision with safety top of mind.

The industry reacts

The ruling has not been warmly received by the industry. Though the AHFA supports a mandatory furniture stability rule, it has stated that the complexity of the proposed testing requirements in the CPSC rule will make it unenforceable. The organization also opposes a safety rating, instead favoring a pass/fail system of compliance, akin to the FDA’s approvals for pharmaceuticals (ibuprofen is simply FDA approved, it doesn’t get a “grade”).

It’s not hard to see their argument—after all, who would want to buy a dresser that was deemed less stable than another, especially when shopping with a nursery in mind? Take that thought a step further: Does knowing a product’s comparative safety rating and choosing it anyway open a designer (or consumer) up to liability in the event of an accident?

On December 5, the AHFA, along with the Mississippi Manufacturers Association and the Mississippi Economic Council, filed a petition to have the new regulations deemed unlawful. They’re also hoping to stall the new standards. On December 12, the AHFA filed a motion to delay the rule’s effective date, arguing that the May 2023 deadline should be postponed until the court rules on the prior petition. “Without a stay of the CPSC rule’s effective date, manufacturers will incur a significant burden between now and the May 24 effective date as they make design, construction and marketing changes to comply with a rule that has an uncertain future,” the motion states.

Individual manufacturers that were asked to comment for this story all declined. Potential sources deemed the issue too fraught to talk about on the record. It’s easy to see why. Coming out hard against the ruling could be seen as being in favor of lax safety standards that could endanger kids. Coming out in favor means a more complicated and costly manufacturing process and a higher price for the end customer. It’s an unenviable position.

There also may be another reason for the silence: The new standards are confusing. The regulations consist of hundreds of pages of highly technical documents. Without being an engineering expert, claiming to totally understand the rulings would be a risky bet.

Time to redesign

In almost all cases, the CPSC’s proposed changes would require redesigning existing and future CSUs in order to achieve even the minimum rating of 1. As outlined by the AHFA, this could include shortening drawer extensions, adding drawer interlocks so that only one drawer can open at a time, adding counterweight to the back of units, or widening cases.

At face value, drawer interlocks seem to be the easiest precautionary measure. But retrofitting existing case pieces isn’t so simple—and it’s unclear how such a design feature would be applied in ready-to-assemble furniture styles that make up the bulk of the mid- to low-end of the market. A consumer armed with only an Allen wrench might be hard-pressed to install such a system.

While the CPSC’s new rule aims to raise safety standards, increased costs could be an unintended consequence. If manufacturers are forced to pay for safety test labs, new packaging, instructions and sales materials, those costs will be passed along to consumers and possibly adversely impact low-income demographics. “Families with young children in America today already face extreme financial pressures,” said AHFA CEO Andy Counts in a statement. “The CPSC rule makes new, compliant dressers and chests less affordable and more out of reach.”

An internal briefing on the rule made public by the CPSC acknowledges that possibility, saying: “The [final rule] could have a disproportionate impact on lower-income consumers and others who desired less expensive CSUs; but would also provide those consumers with the benefit of a reduced risk of injuries and deaths.”

Battle lines

The CPSC will have 10 days to file a brief responding to the AHFA’s motion to delay, after which the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit will render a decision about whether to pause the rule’s effective date pending further review. So, an inkling of where this melee is headed could come early in 2023. If it’s denied, manufacturers will have to make a mad dash to meet the May deadline.

Homepage image: ©Africa Studio/Adobe Stock