For Dedon, home is outdoors. Since its founding in 1990, the Lüneburg, Germany–headquartered company has explored the aesthetic and performance possibilities of luxury outdoor furnishings. By applying artisanal weaving techniques to its innovative extruded fiber and collaborating with international design talents on visionary collections, the brand creates elegant modern products that don’t just celebrate life outside—they transform it.

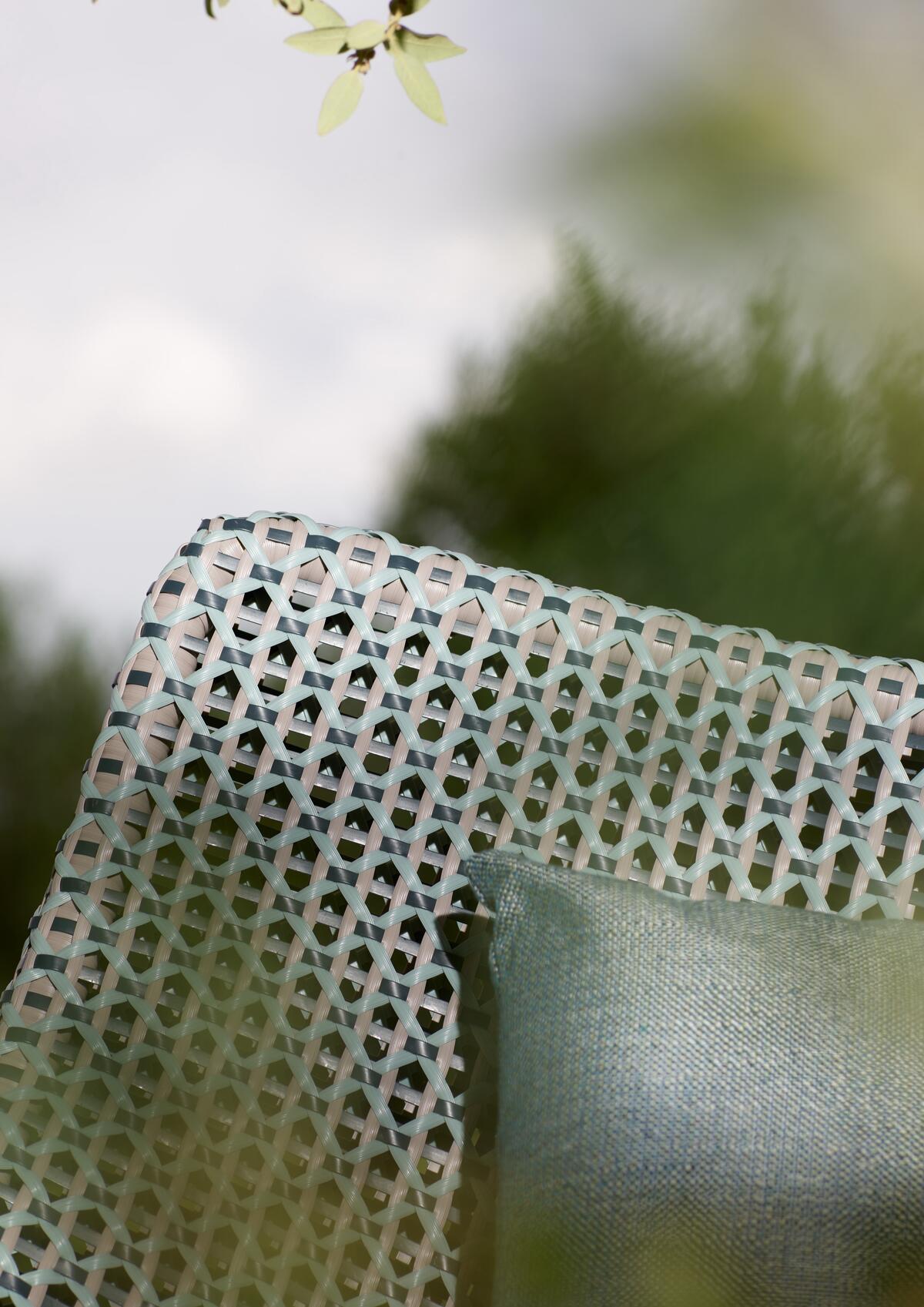

Developed in partnership with award-winning German designer Sebastian Herkner, the Mbrace series exemplifies the best of Dedon’s offerings and has become one of its most popular lines. Intricately interwoven in a distinctive meshlike triaxial pattern, eminently comfortable with or without cushions and economically proportioned on either a warm teakwood or smooth powder-coated aluminum base, the weatherproof, wide-backed seating provides an enveloping embrace. In fact, Herkner himself often retreats to his own daybed for an afternoon catnap on the terrace. Like all of Dedon’s portfolio, the luxurious yet laid-back Mbrace family is hand-woven in the Philippines by master artisans, who bring generations of tradition to every gesture. Business of Home editor in chief Kaitlin Petersen spoke with Herkner about his profound respect for craftsmanship, meticulous approach to color palettes—and newfound appreciation of local produce.

Kaitlin Petersen: How did your partnership with Dedon begin?

Sebastian Herkner: Dedon is one of my longest-term partners. We worked on the Mbrace collection for almost three years [prior to its debut in 2016]. They invited me to their factory close to the headquarters in Hamburg, where they originate their fiber, and we had a nice conversation. That’s always the starting point: meeting the people and looking behind the scenes to understand what’s typical for the company. For Dedon, that’s their patented fiber. They have seven huge machines extruding it like pasta. Then they ship it to the Philippines, where weavers do their magic.

Dedon is more than 30 years old, and founder Bobby Dekeyser began by using rattan and bamboo for outdoor pieces, but those materials are not weather-resistant [for] autumn and winter in Europe. Eventually he came up with this specific fiber. I’d never made a plastic product before, and I’d never use plastic for an indoor chair, but here it really makes sense because the products have a 10-year guarantee for all weather conditions. In a desert, in the tundra, neither heat nor snow, sun nor rain can damage them. [My husband and I] have had Mbrace on our terrace for six years already and the colors stay true.

Dedon was impressed by the way I work with colors, which is why they asked me to collaborate. They wanted to bring some new colorways to the brand.

We started with the idea for the design: OK, Dedon has a lot of big cubic sofas. Let’s do something complementary. Let’s take indoor [styles], like a daybed, a rocking chair, a high-back chair, a low-back chair, and create them for outdoors. Mbrace was the first line to use extruded fiber and teakwood together, and it’s an interesting balance, combining synthetic and natural materials.

Concept design was in Lüneburg, but product development was in Cebu. I went on-site because I was curious to see how the items were made. They’d ship the prototypes back to Germany for review.

Petersen: How did seeing the weaving capabilities in person change the product design?

Herkner: We started with a cardboard model, followed by an aluminum frame. And then we developed the Mbrace weave with three colors: orange, blue and purple, for example. They mix together, almost becoming a new color. And I wanted to have an open weave so you would feel the air filtering through and hear the birds around you. But this took a while! The weavers begin with hundreds of meters of fiber—they look like my hair in the morning, going in every which direction. And they have to weave them so precisely that all the pieces look the same. There are maybe 100 weavers [at the facility in Cebu], and [each person] works two or three days on one chair. I tried it once for 10 minutes and was like, “Oh, my God, I cannot weave one minute more.”

Petersen: You mentioned shying away from plastic in most applications. What opportunities did the material allow you here?

Herkner: The great advantage is that you can work with all kinds of colors and it’s fade-resistant. Dedon has its own testing lab, and we tried different combinations. The red was not quite right at first; it faded. So they changed the ingredients and the composition to extrude a darker tone of red, and then it was stable. Dedon tests all the fibers over half a year in the lab with seawater, wind, sunshine—that’s the best way to get a long-lasting product. It’s also about sustainability. Dedon gets copied a lot [by big-box home goods stores], but those products last two years and then the fiber starts to crack or the color begins to fade. I always say design is an investment, like an artwork or an apartment or a classic car. Something cheap or damaged, you’ll just throw it away.

Petersen: Thinking about your experiments with color, how did you land on the combinations that you did?

Herkner: We began with Mbrace in three colorways. There was a red, a blue and a more mineral one. A pepper, too, which is a bestseller. It’s like producing textiles—we do several swatches and samples. Then we add new color combinations based on feedback: Oh, the Florida market prefers white? We did a sea salt combination, which is more or less three white fibers together. We did a chestnut variation for another market. When you weave the different colored fibers, the effect can be completely unexpected. You cannot really simulate it in Photoshop. You need to see it.

Petersen: Is this a traditional weaving technique? You prototype the weave pattern?

Herkner: The pattern we create in our studio. Then the weavers in Cebu translate it into a tactile, dimensional shape.

Petersen: You’re also assigning each color to a position in the weave, correct? Does that change how it looks?

Herkner: Completely. If the diagonal fibers are now brown and the horizontal ones are now light, it changes the effect completely.

Petersen: Even if you’re working with the same colors but in different positions?

Herkner: Exactly. It completely changes the character of the chair. And then you have the powder coating. Recently, we introduced an aluminum base that is die-cast in one piece specifically for the Mbrace dining chair. Thinking about cruise ships and other hospitality spaces, some [customers] want their own color combinations—maybe a green powder-coated base with a pepper weave, or a terra cotta one with brown fibers. We now offer more than 70 combinations of base material, furniture type and fiber colorway.

Petersen: The hand is so special.

Herkner: Crafted treasures, crafted emotions, crafted stories—that’s what’s important. Just imagine Venice without glass. Germany, Japan, England: Every country has its own way of shaping a material. And often, craftsmanship is passed down; it’s in the DNA. I don’t know if we will have craftspeople in 20 years, but they’re so important for interiors, architecture, furniture and fashion design. Not 3D printing done by robot. No, it’s made by a human being, a pair of hands. So I try to be an ambassador for craftsmanship because they are the real heroes.

Petersen: With the surge in demand for outdoor furniture through the pandemic, are people living with these products differently now?

Herkner: I think they appreciate them more. There are still a lot of people working from home. Companies try to get them back to the office. They don’t want to go. I take my nap in my own Mbrace daybed in the afternoon sometimes, and it’s comfortable and beautiful with or without pillows, which is unique for outdoor furniture. You can work in the chair, chill, have conversations. Its uses are quite universal.

Petersen: What does the design process look like to achieve that feeling of being “embraced,” as its name suggests?

Herkner: Well, weaving is tricky, because you cannot do all the shapes. The more aluminum [that’s used for the framework], the [more the] price goes up. More welding, more pillows—the price goes up. You cannot do completely wild organic shapes without a complicated internal structure to support it. So it was important to have a frame in the studio to start weaving or gluing cardboard on top of in order to create the curvature and shape the surfaces. And then go to the Philippines for the actual prototypes.

The biggest privilege is to travel. Before the pandemic, I was traveling like crazy. Then suddenly I had time to go to the local farmers’ market to buy my vegetables and meat. It changed the way I think about where products come from. If you have good ingredients, you cook in a different way. A chef is similar to a designer: You need the right ingredients, the right tools, ideas, fantasy, experience to create a nice dish.

Petersen: How does fantasy and inspiration play into your work?

Herkner: During Covid, it was fantastic just to travel around Germany to places I’d never been before. You take hundreds of pictures to help find the right story [for a collection]. And you need the right partner, like Dedon. Without a strong partner, you’re left with a lot of stories or sketches in your desk drawer.

My father was an electrician, my mother a nurse. We had a great life, but it was nothing fancy. It was not, “Tomorrow we jet off to Mexico!” For vacations, we went camping in France. Even though she’s not religious, my mother loves churches. Two weeks’ camping meant 50 different church visits to see the beauty of the architecture, the stained-glass windows. Back then, I would have rather gone to the beach. But now I realize it may be the foundation of my career.

The first time I flew outside of Europe was for work. And then Dedon invited me to the Philippines. I’d never even been to a Filipino restaurant. I’d never had sushi. I invited my parents to New York, and next year I’ll take them to Copenhagen, to give something back, because now I can.

Petersen: How did your upbringing shape your idea of what an object should be in a home?

Herkner: It needs to tell a story and support its owner; it needs to serve them as long as possible. It needs to be functional. But in the end, it needs to be beautiful. Sometimes it’s love at second sight: If you fall in love with something or understand it immediately, sometimes you forget it just as easily. Sometimes it’s good or brave to swim against the tide, create something different that people will discuss and interact with and think about after. And I don’t care if people don’t like a product [I designed]. If everyone likes it, maybe it’s not a good product.

Petersen: With Mbrace, what felt like this kind of risk?

Herkner: I heard a lot from the dealer side about the proportions because Dedon products are usually big. But I said, “Come on, think about urban living, the balconies of skyscrapers in New York or Frankfurt.” You want the same comfort, the same quality, so let’s do smaller chairs. Because the future is vertical cities. Just look at The Line, this crazy project in Saudi Arabia. They will have small balconies. It’s not about massive sofas.

Petersen: And you’ve been proven correct: The Mbrace collection is so popular.

Herkner: The nicest aspect of social media is seeing people [using Mbrace] or getting a message: “We’ve loved your chair for a couple of years, and now we’ve finally got our own,” or “We saved up money to afford one.” I love those. I think design is the best of all worlds, with nice surroundings and nice people.

Petersen: It’s true.

Herkner: I cannot think of a better job. Maybe chef. I do like cookies.

This story is a paid promotion and was created in partnership with Dedon.

Homepage image: As its name suggests, Dedon’s Mbrace collection of indoor-outdoor furnishings is designed to envelope the seater and is supremely comfortable with or without cushions | Courtesy of Dedon