Sight Unseen has achieved a rare honor for a publication: adjective status. Founded in 2009 by design journalists Jill Singer and Monica Khemsurov, the online design site has become synonymous with a particular genre of contemporary maker: playful, edgy, a touch of deco here, a touch of Memphis there. In the design world’s cooler corners, it’s not uncommon to hear a piece—say, an angular pastel pink lamp—described as “kinda Sight Unseen–y.”

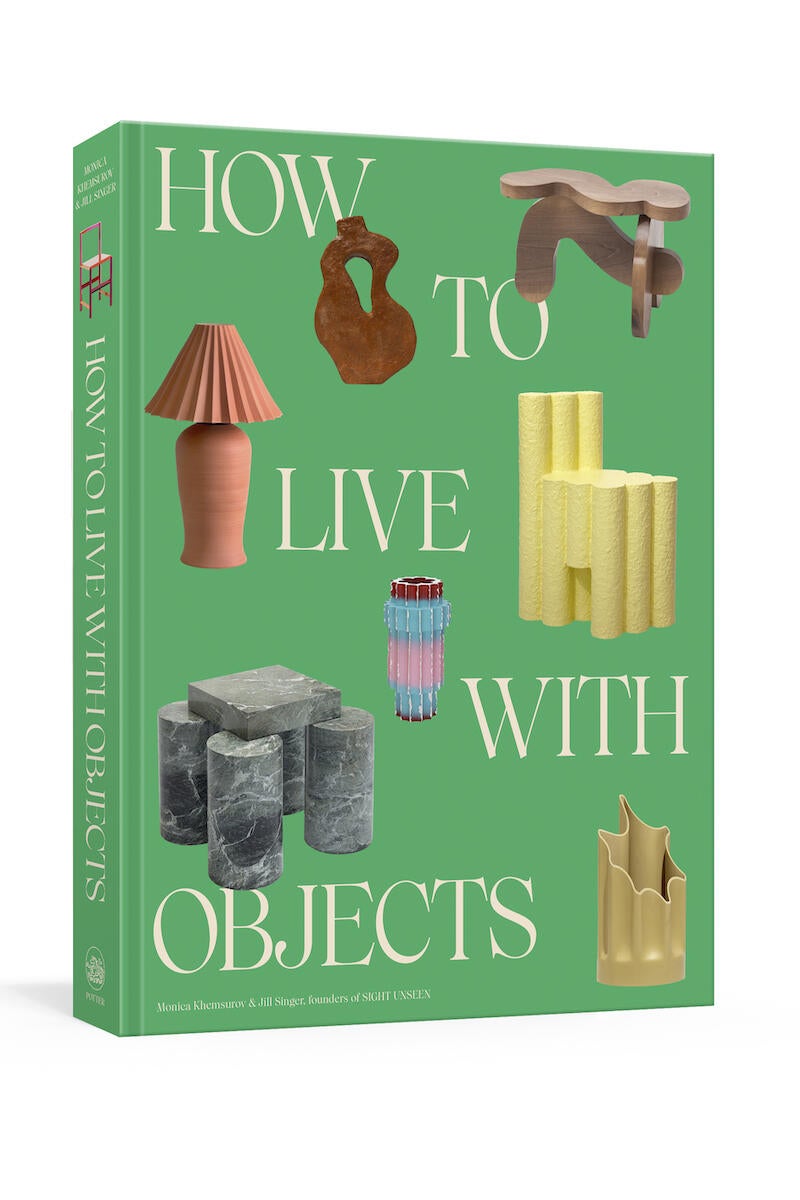

Now Singer and Khemsurov are releasing their first book, How to Live With Objects. It’s not, they’re careful to point out, a retrospective. Rather, the book is both a how-to and a mission statement. It asks the reader to set aside the notion of crafting their home like a meticulous symphony of color, texture and utility, and instead to obsess over objects (a term that mostly refers to decorative pieces, lighting and chairs). The notion may give some interior designers pause, but it unlocks a useful reminder: If you’re surrounded by things you love, you’ll have a happy home.

Business of Home spoke with Singer about the economics of contemporary design, how to live with “weird” objects, and how the avant-garde makes its way into the mainstream.

You cover this interesting world of contemporary makers and small design brands that has really blossomed in the past decade. I’m curious about the economics of that scene. When you first started covering it, how did these designers think they would be making money?

In the early 2000s, if you wanted to make money as a designer, you went to work for Frog or Ideo. Or maybe you licensed your designs to a European company—you’d try to catch the eye of Giulio Cappellini. That was all you could really do. But then the internet led to this explosion of people realizing they could sell directly. So you had lots of people experimenting with making small goods—a brand like Fort Standard would be making chairs but also stuff they could easily get to consumers, like bottle openers—to build a client base that wanted to invest in the bigger stuff.

At the same time, there was more infrastructure coming up. You had the Made section of the [now defunct] AD Design Show, our show Offsite, the Collective Design fair—it was all helping to grow an audience for these kinds of designers, and it worked.

Do those economics still apply?

It’s almost going in the other direction now. I think designers have realized that it’s so hard to make money just from making smalls that everyone’s trying to find the big thing they can make—almost like [New York–based lighting designer] Lindsey Adelman, who has a $40,000 chandelier because that’s going to have the most profit margin.

The book encourages readers to develop their own taste in contemporary design. But I have to confess that, if I’m going to, say, Carpenters Workshop and browsing these incredibly expensive design pieces, I’d want an interior designer with me just to help navigate it. It’s an intimidating world.

For sure. Monica and I don’t have the budget for those kinds of pieces, but we go to look at them to stay educated about the ideas that are percolating and the forms that are interesting to designers right now. A lot of people will go to an Agnes Martin exhibition at the Guggenheim and never think about buying a painting—that’s how I think about the higher end of contemporary design. Most people won’t go out and buy it, but the aesthetics trickle down. You’re training your eye.

One section of the book I love is this collection of objects labeled as “embracing discomfort”—stuff that’s almost deliberately tacky or ugly. Do you have any of that in your own home?

I don’t know if I have anything grotesque in my house, though I definitely have some things where my mom will be like, “Well, that’s interesting.” I think a lot of things that are considered avant-garde become mainstream more quickly now because they’re on social media so much.

That’s a good point. Today’s weird piece is tomorrow’s retail collection. Even so, I think there is a hesitation to really embrace “wacky” design in your own home.

I think that’s part of our job at Sight Unseen—making people comfortable with things they might have been uncomfortable with before. A lot of it is education. I almost liken it to progressive politics. Once you start formulating an idea, you just keep moving and becoming more and more radicalized, right?

In my head, there’s a real divide between the world of Sight Unseen and the more mainstream world of interior design showrooms and workrooms. I’m curious if you think that line is blurring.

Part of it is a client thing—you have to have a client who wants the stranger pieces. But because we have a store on 1stDibs, we have a bit of insight into designers who are sourcing stuff we list, and it’s people who you’d definitely consider part of the mainstream design world.

It’s a pop culture thing too. There was a Trueing chandelier in a house tour that [social media influencer and artist] Emma Chamberlain just did with AD, and you saw so many people commenting, “What is that chandelier? I want that in my house.” Little moments like that make people aware of what’s going on in contemporary design.

Homepage image: A living room designed by Brussels-based art and design curator Helene Rebelo | Courtesy of Sight Unseen